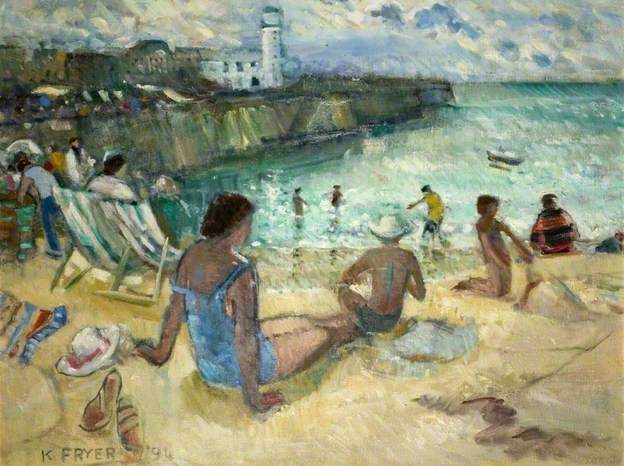

Katherine Mary Fryer, who will be 105 on August 26th and lives in Harborne, Birmingham, painted Morning on the Beach, Scarborough in 1994. There are more of her paintings here.

Katherine Mary Fryer, who will be 105 on August 26th and lives in Harborne, Birmingham, painted Morning on the Beach, Scarborough in 1994. There are more of her paintings here.

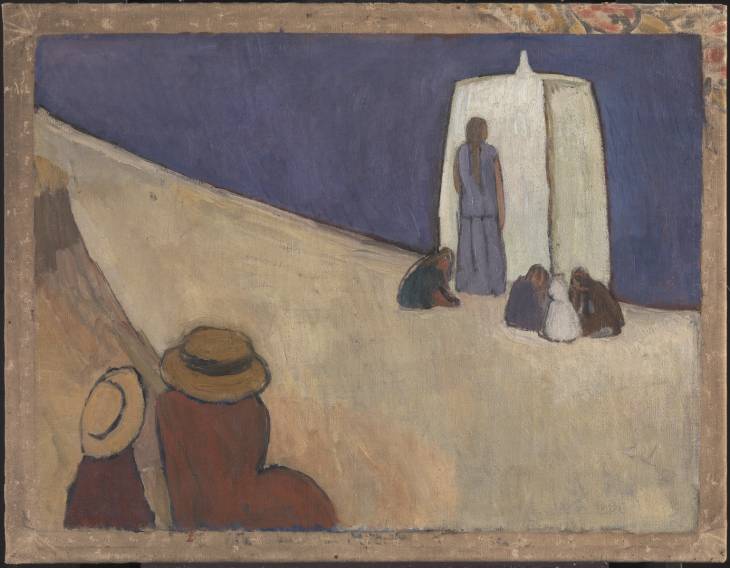

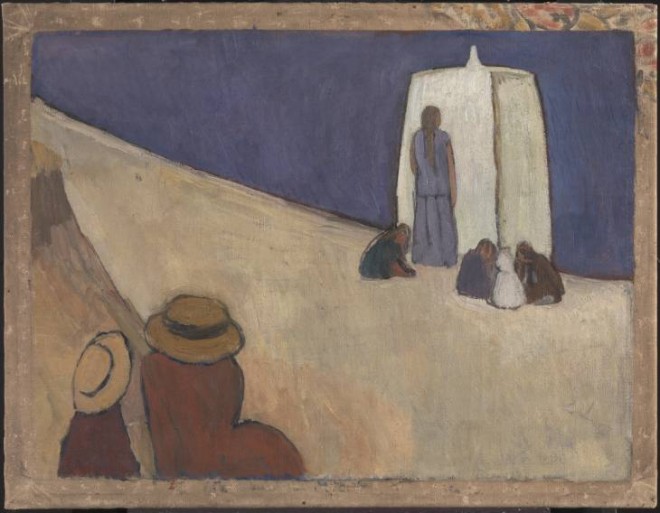

Constance Oliver At the Seaside. The date of this painting is unknown, and indeed apparently nothing is known about the artist except that she died in 1940. It’s at Bristol Museum and on their website is a sad little notice: ‘This object is in store, please contact the Museum to arrange to see the object.’ There is something about the repeated word object that is so, well, dispiriting. But what a glorious painting. (Stop press: thanks to a Persephone reader who discovered here that ‘painters such as Paul Nash and Constance Oliver lived through, and vividly recorded, the experience of the Great War. She studied art at the Slade School and after graduating she specialised in portraits and landscapes working in both oil and watercolours.’ And it is curiously appropriate, given that she painted during the First World War – but where are her paintings? – that she is on the Post on August 4th.)

Women painters and the seaside is the theme this week since, peaceful as it is in London, a bit of our collective hearts are under sun umbrellas on the beach. Vanessa Bell (so wonderfully played by Eve Best in Life in Squares) painted Studland Beach in 1912. It’s at the Tate and this is what their website says: ‘Studland Beach is in a quiet bay in Dorset. The idea of the beach as a place for leisure activities was relatively new in 1912. It is a sign of their modernity that Vanessa Bell and her Bloomsbury Group friends holidayed there. This is one of several works by Bell from 1911–2 which show a debt to Matisse in their simplified design and bold colouring. Though an exercise in what her friends called “significant form” (emphasising form rather than subject matter), the picture retains some of the feel of a sunny day spent on the sand and in the water.’ On the back of the painting, apparently, is a Group of Male Nudes by Duncan Grant.

After the shock of her husband’s death, and the traumas of the war, Nova Pilbeam retreated into fairly minor film parts during the 1940s. In 1950 she remarried and thereafter devoted herself to domesticity. This is where she lived – until the death last week of the greatest actress who never was.

The New York based artist Duncan Hannah adored Nova Pilbeam from afar, often painting her and even, when he was in London, hovering outside her house (in Grove Terrace, Kentish Town) in the hope of seeing her – without apparently without ever doing so. This is ‘Nova with a Faraway Look’ 2007, available here, and here is a fascinating Remodelista article about Duncan Hannah and his work.

‘After Young and Innocent (1937) Nova Pilbeam seemed destined for a great screen career, but it somehow failed to materialise’ (Daily Telegraph obituary). It is possible that cinematic success had come too early. It is also possible that she was too intelligent to lead the kind of life required by the movie moguls. And undoubtedly the death of her husband Penrose Tennyson in a plane crash in 1941, two years after their marriage, affected her hugely, and having always preferred the stage to film, after his death she played only minor film roles. Yet although her stage career started well (Peter Pan, Juliet for the Old Vic) it too faded away.

Nova Pilbeam’s first role was in Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much in 1934 when she was 14. ‘Even at that time,’Hitchcock said of her, ‘she had the intelligence of a fully grown woman. She had plenty of confidence and ideas of her own.’ In 1937 she appeared in his Young and Innocent. Over the next ten years she was in a dozen more films .

Nova Pilbeam –the greatest British actress that never was – has died and will be the subject of the Post this week. Born in 1919 in Wimbledon, her career initially got off to a fizzing start. This is what one Nova Pilbeam website says about her here: ‘David O Selznick considered she had the potential to be a star for the world market. He wanted to cast her as Mrs De Winter in Rebecca (1940). It didn’t happen. Instead, Nova Pilbeam is a forgotten actress with an odd name, except for those who have seen her in a film.’

Mapperton is actually a bit grander than the filmmakers would have us believe (here is the staircase) and yet it was the perfect background for the film. A visit is heartily recommended.

The very spot where yesterday’s photograph from the film was taken and where we had a wonderful walk.