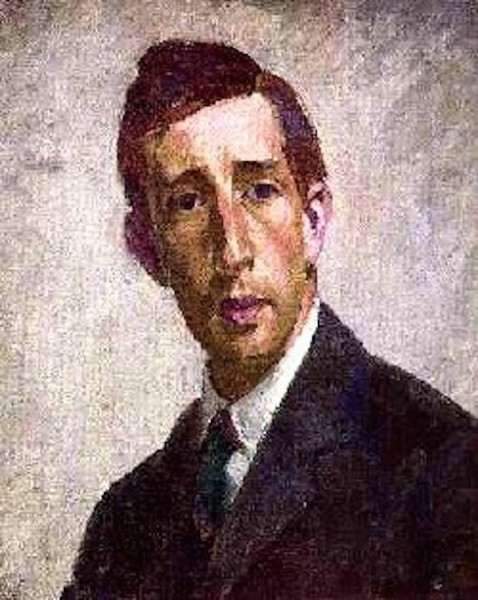

‘I have always been greatly attracted by the undiluted female mind, as well as by the female body,’ writes Leonard Woolf in the second volume of his autobiography. The female mind was in his view ‘gentler, more sensitive, more civilised’, than the male, but to access it a man must listen attentively, which few men did. He taught himself to listen. The central subject of The Wise Virgins is the emotional, intellectual and social journey of Harry Davis, but it is played out with a wide cast of markedly different women, and only a small number of men for the most part either somewhat faceless or comic and not of the listening sort.

In her life of Leonard Woolf, Victoria Glendinning describes The Wise Virgins as ‘brazenly autobiographical’, and critics and readers have had no difficulty in identifying many of the characters: Mrs Davis is Mrs Woolf, the Lawrences are the Stephens family, Camilla and Katharine, Virginia and Vanessa; the Garlands are the Woolfs’ Putney neighbours and Harry is Leonard, a very dark side of Leonard, a ‘shadow’ in whom he exposes and works out some of his own turmoil, anger, cruelty even. Woolf sets his anti-hero off on a route similar to his own, and with much of his own baggage, confronts him with similar dilemmas, but leaves him finally heading miserably down the path that he himself avoided. It is an autobiographical novel, but of the ‘what if’ school.

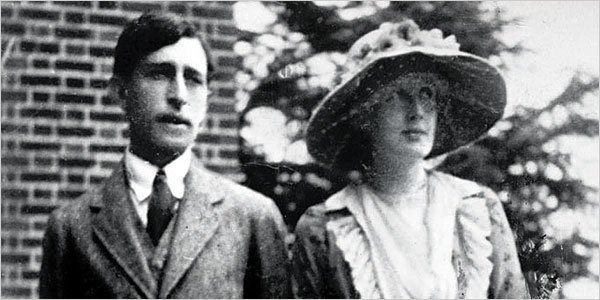

Woolf began The Wise Virgins while on honeymoon. He and Virginia were married on 10th August 1912, they left England the following week and returned three months later, having travelled through France, Spain and Italy. Virginia read Le Rouge et le Noir, Pendennis, The Antiquary, Charlotte Yonge’s The Heir of Radcliffe, D.H. Lawrence’s The Trespasser, and Crime and Punishment. Leonard started writing his second novel. What Virginia refers to in a letter to Duncan Grant as ‘the proper business of bed’ seems to have taken second place, if indeed much place at all. ‘The marriage’, writes Victoria Glendenning in her life of Leonard Woolf, ‘was consummated, not infrequently, but incompletely.’ Leonard Woolf, the married (unconventionally but not unhappily – he had made the right choice) man, established, by marriage, in a milieu remote in so many ways from that in which he was born, uses his novel to reflect on the differences between the two and justify his rejection of the one, while giving vent to his occasional angry impatience with the other.

The contempt in which his alter-ego, a Jew like him (and like him both proud of his Jewishness and uncomfortable with it), holds his family and their suburban Richstead neighbours, is weighed against the fear of being excluded or condescended to by the intellectual, Gentile, sophisticates of Bloomsbury.

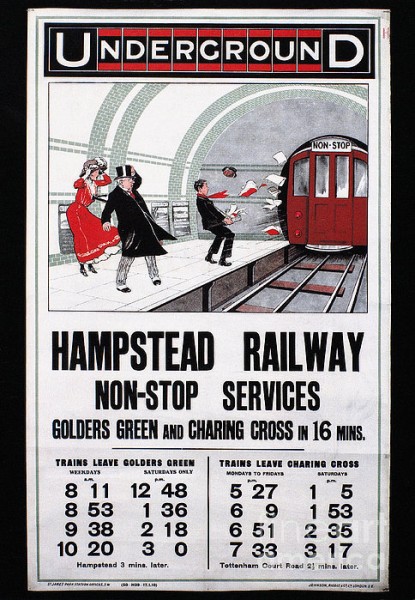

The name itself, Richstead, an elision of two other London suburbs, Richmond and Hampstead, speaks of the extent to which its residents value material wealth above matters of the mind. Richstead is Woolf’s Putney, the suburb to which his mother took her large family, when the reduced fortunes of widowhood forced them to leave Kensington. Woolf encapsulates his hatred of the snobbish parochialism of suburbia in Mrs Davis, dull, self-pitying, possessive and embarrassingly Jewish – ‘The big curved nose, the curling full lips, the great brown eyes would have made a fine old woman of her, if she had been squatting under a palm tree with a white linen cloth thrown over her head and drawn round her heavy oval face’, a crude, barely disguised portrait of his own mother which, unsurprisingly, cause deep offence to her and to his siblings.

From the opening pages of the novel the line is drawn between ‘intellectual people who really do live in London’ and those they despise who live in red-brick villas, ‘all exactly the same, like the people who live in them.’ Two different worlds just a short ride apart on the newly built tube.

Harry has succeeded in crossing the line. We are not told how – there are no back stories – but he has made a bid for freedom, not following his father to make more money in the city, but going instead to art school. There a fellow student provides an entrée into the cerebral urban élite, where he can temporarily forget the Richstead drawing rooms, in which people (mostly women) sit upright in their chairs and talk of servants, and shops and the price of mutton; he can exchange them for the deep armchairs of Bloomsbury, where conversation leaps from poetry to architecture to life and love and truth. These are the Lawrences, Camilla and Katharine, their father and (male) friends. In the Lawrence circle they address each other by their Christian names, and men and women talk freely together and between themselves (so convincing is the conversation between the two sisters on married love that one can only imagine that Woolf’s practice of listening to women extended to eavesdropping). Harry’s attempts to raise Richstead conversation to that of Bloomsbury has little success even with the compliant Gwen, who is excited by it but confused – they were talking ‘like people talked in books’.

Gwen is the youngest of the four Garland girls, each in their way, carefully drawn representative types of Edwardian English womanhood. Ethel, the eldest, is thirty-seven, unmarried and doomed to remain so, sweet, patient and ‘curiously unintelligent’, Janet, ‘one of those female “sports” born into so many families in the eighties’ – presumably ‘sport’ is code for lesbian – who, had she been born in Kensington rather than Richstead, might have been a militant suffragette. May reads library novels, has sturdy legs, and grumbles to herself that ‘these Jews [the Davises] should come and dump themselves down at Richstead and in her set’, before swiftly turning her thoughts as to what to wear should young Mr Davis come to visit (Leonard Woolf knows how girls think!). Totally at home in ‘her set’, she wants nothing more than to marry the local vicar, the wonderfully comic Mr Macausland, who ‘had taken a bad third-class degree at Cambridge’, and whose ‘intellectual claims rested upon his lectures on Browning and a three weeks’ personally conducted tour in Italy.’ The garden party master-minded by the vicar in aid of ‘The Poor Dear Things’ is a keenly observed and wonderfully witty set piece.

Incidentally, but interestingly, Leonard Woolf also says critically of Mr Macausland that he had ‘one manner for men and another for women’: how very modern, and how shocked he would be to find that one hundred years on, there are still men in England of whom the same could be said. And for all its enlightened attitudes Bloomsbury is not without its comedy characters with decidedly old-fashioned attitudes: Arthur Woodhouse with ‘his fat, round little body and his little, round, fat mind’, happy ‘when alone between the sheets, to recognise how susceptible he was and how virile, and still happier to believe that other people, including women, recognised it’. And the once handsome ‘Lion’ Wilton, who thirty years earlier would have young women falling at his feet: ‘Hockey and women’s suffrage had, however, spoilt his market, which was still fairly large among married and older women who have not entirely lost their love of submission and of being ill-treated by the male.’

The youngest and the prettiest, Gwen is also the most vulnerable of the Garland sisters, because she doesn’t protect herself in the same way behind the conventions of her class and her ‘set’. She is an easy catch for Harry, who plays with her, more cruelly perhaps than he realises. He is attracted by the idea of educating her, moulding her, and she is a more than willing pupil, on who whom to try out the lessons he is learning from his new friends in Bloomsbury. Virginia, when Leonard first kissed her, had felt ‘like a rock’. Camilla, whom Harry loves, is friendly but physically cold (her sister, Katharine, by contrast is a creature of ‘flesh and blood’ and it is she Harry pictures across the marital breakfast table – brazenly autobiographical?). Gwen, whom he doesn’t love, is hotly responsive. A more experienced teacher might have foreseen the consequences.

His struggle to define and determine his individuality mirrors Leonard’s, but ultimately fails when, unlike Leonard, he gives way to the force of sexual desire. Having eaten of the apple, Harry Davis must say goodbye to the Paradise of Bloomsbury, and spend the rest of his days in a dreary corner of suburban Richstead.