Unusually for a Persephone book, the plot of The Blank Wall turns on murder and blackmail. ‘…the top suspense writer of them all’, wrote Raymond Chandler of Elisabeth Sanxay-Holding, a dream puff for her publishers, in what is generally considered to have been a golden age for crime fiction. ‘Her characters are wonderful’, he added, ‘and she has a sort of inner calm which I find attractive’ – not such good copy for the dust cover, but subtle and perceptive. As a thriller, The Blank Wall is a gripping page-turner, but I found myself torn between racing to the end, and lingering over the eccentric, and unexpected charms of the main players, and the silent musings of Lucia.

It is war-time and Lucia Holley is the thirty-eight year-old wife of Tom, away fighting in the Pacific, and mother of fifteen year old, straight-laced, David, and the wayward Beatrice, seventeen going on eighteen, whose reckless affair with Ted Darby, a twice-married dealer in obscene pictures, triggers a chain of events that turns Lucia’s life upside down.

Elisabeth Sanxay-Holding wrote eighteen crime novels as well as short stories in the genre, of which several were turned into films, The Blank Wall, being filmed twice, first as The Reckless Moment in 1949, starring James Mason and Joan Bennett, and later as The Deep End in 2001, starring Goran Visnijc and Tilda Swinton. Both films made significant changes to the plot (although, in the extracts I have seen, the 1949 version sticks closely to S-H’s dialogue, proving just how good an ear she had), the 2001 version shifting the love interest from a heterosexual to a homosexual liaison, and both sidelining the characters of Lucia’s (Margaret in The Deep End) elderly fatherly and her tireless maid, and, most radically, changing the period.

With husbands merely away working, for finite periods of time, on the end of telephones, with no threat of widowhood, or shortages of food, or petrol, or friends, Lucia’s celluloid incarnations have not been toughened as she has. Lucia Holley of The Blank Wall has been formed by the war. For three years she has struggled to hold family and home together, in a rented house, in a strange village.

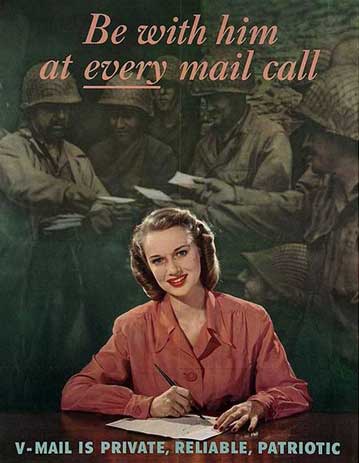

Her contact with Tom via V-mail, the forces’ post, is erratic on his side, nightly on hers, but ever less substantial. Her gentle and gentlemanly English father is kind but ineffectual. His one show of manliness has dreadful consequences, of which he remains in blissful ignorance: it is he, not Bee as in The Reckless Moment, or her brother as in The Deep End, who, inadvertently causes the death of Ted Darby (not too many spoilers, if I can help it!). of whom, most importantly, he knows nothing other than that his daughter disapproves of him.

Lucia discovers the body, realises what has happened, hides the body, tells no-one. What else can she do? ‘She had the resourcefulness of the mother, the domestic woman, accustomed to emergencies … For years she had been the person who was responsible in an emergency.’ Ensuring that her daughter break off an unsuitable relationship, concealing a corpse, protecting her father – all in a day’s work for a wartime wife, along with queuing for the week’s rations, struggling home with heavy bags, and digging her Victory garden. And yet Lucia ‘had always been faintly disappointed in herself … most of all disappointed in herself as a mother.’ And her life is about to get far more complicated with the arrival of Nagle, a blackmailer and his Irish sidekick, Martin Donnelly, holding a stack of indiscreet letters from Beatrice to Ted.

The task of protecting her family will test her courage and resourcefulness to the limit, and will be doubly difficult for having to be kept the secret from them: from Bee, who sees herself as a modern young woman, unappreciative of Lucia’s efforts to keep her children fed and tidy, and ignorant of the risks she is taking to protect her (Bee’s) reputation, who despises her mother’s life for its dullness and lack of adventure; from her father whose unwavering sense of honesty would drive him straight to the police; and from her husband to whom she sends brief notes on the dullness of life – there is something gently humorous in the stark contrast between the astonishing drama facing Lucia and the unreality of her tender mendacious V-mails (desperate for something to write, she resorts on one occasion to retrieving an old rejected draft from the waste paper-basket). While she guards them, her children are anxious to protect their mother from the charms of Donnelly, the elegant and mysterious lothario, who has taken to visiting them. What a tangled web we weave …

The rock in the household is Sybil, the coloured (in 1940s American speak) help. Sybil is understanding, and brave and reticent. She has worked for Lucia for eight years, covering up for her employer’s failings as a housekeeper, and as a gardener, even lending her money, for Lucia is absent-minded, and careless, and not a little self-absorbed.

Lucia loves and trusts Sybil but she knows nothing about her, doesn’t know that she is married, that she lost a baby, that her husband has been in prison for eighteen years for accidentally killing a man – ironically mirroring the killing of Ted Darby for which none of the Harper family will be punished. ‘Maybe when he gets out,’ says Lucia, ‘you can take a trip.’ Lucia really doesn’t understand a thing about Sybil’s life but she shares her belief, ‘that life was incalculable, and that the only shield against injustice was courage.’

Justice does not necessarily equate with the law. Old Mr Harper’s appraisal of crime fiction is accurate in the case of The Blank Wall, ‘They generally show the murdered person as someone you can’t waste any pity on’. Our sympathies are all with Lucia, an accessory after the fact if ever there was one, and with Donnelly, the compassionate blackmailer, the generous black-marketeer, the honest thief. We like him for his soft heart, for his imaginative, practical giving – ham, beef, a reliable laundry service (did any other reader mistake the young man introducing himself as ‘Regal Snowdrop’ for another member of the criminal fraternity, but with an unusual name?).

We love Lucia for her self-deprecating reflections, for her wistful recollections of her children’s early years, for her sense of priorities – she delays meeting Donnelly’s vicious partner not from fear, but in order to read her teenage son’s entry for a short story competition. We love her, when she interrupts plans for disposing of a second body to reprimand Donnelly for his sleeping pill habit. We love her for her sense of the ridiculous, ‘I’m just going to take a little drive with a blackmailer’, for ensuring that she always dresses appropriately whatever the circumstances – has any Persephone heroine ever changed outfits quite so often?

Most of we love her for her fierce dedication to her family, a dedication that has evolved over the years and is tested to its limits, and her capacity to accept the life that she has been given, to put a good face on things, to hide her tears, to know that honesty may not always be the best policy, in small things, and sometimes in big ones. A most unusual Persephone war-time heroine, but with much in common with her British ‘sisters’.