‘A darting sunfish,’ wrote Angus Wilson of Frances Towers. She would surely have loved the image. The play of light and dark, shadows and reflections, what one of her characters refers to as the ‘chiaroscuro in the picture of her life’, ripples through all these short stories, often literally. Furnished is waxed to a sheen, silver polished, jewels scintillate, a witch’s ball hangs in a cottage sitting-room. But there is something mysterious, unstable about light; reflected light is particularly unreliable, revealing, concealing and distorting reality.

Violet, a strange, diminutive housemaid arrives and the first sign of her unsettling power over her employers is the ‘darker stranger glow of the furniture’. The brass witch’s ball reflects ‘a small enchanted garden on one side and on the other a mysterious white room’, but Lucy and Florence’s garden, in ‘The Chosen and the Rejected’, is not enchanted but bordered by a sinister wood, ‘a beggarly, untidy place, rather sodden, with a smell of something dead in it.’ Their sitting-room is neither white, nor mysterious, and the diamonds dripping from the wrist of their far richer neighbour, whose unexpected visit will change their lives, as Violet changed those of the Titmusses, far from casting a glitter over it, seemed ‘to attract and hold all the light in the room’. Light can obscure. In ‘Lucinda’ Venetia Quarles complains that her mother, with her excess of common-sense, is ‘like electric light in a room which a moonbeam is trying to enter’, preventing her children from seeing the family ghost. She is wrong about the common-sense: Mrs Quarles firmly, and wrongly, believes that the figure she sees reflected in her mirror is the ghost. Mirrors can confuse and more often than not when we are confident of seeing the whole picture and seeing it clearly, we are mistaken.

‘There were no dark corners in our house, and none, it was assumed, in our minds, which, said my mother, were an open book to her’, writes Elsa in ‘Don Juan and the Lily’. But daughters in Towers’ stories are more often than not closed books to their mothers,literally closed books in some cases: Sophy (‘Violet’) and Prissy (‘Tea with Mr Rochester’), although in her case it is the prying eyes of an aunt that she is escaping, commit the truth, their truth, to carefully concealed diaries. Mrs Craigie knows no more about Elsa, than Mrs Dellan knows about her deluded daughter, Elsa’s office friend Anne, who has reinvented herself as Georgia, reconfiguring the world around her at the same time: her employer is no poet, nor when he marries Elsa has he accepted second best.

Anne/Georgialeaves behind the reality of the bookless, flowerless, airless Bayswater house that she shares with her mother, along with her given name. Prissy escapes the careless cruelty of her aunts, Athene and Elena, whose ‘kiss was like the peck of a hen, so perfunctory that it bereft one of affection’, by bouncing a ball ‘to spin out of herself an imaginary world and people it with characters’. The gossamer thin curtain between reality and the world of imagination is torn when Prissy is taken to tea with the man, as it were, of her dreams, Mr Considine, her Mr Rochester (Prissy lives in books, forbidden books), taken along by her aunt ‘as she might have taken a Pekinese or a sunshade’.

Aunt Athene lives in a dully material world, a prosaic world, a poor alternative to the poetic universe of the imagination. Aunt Esse, in the final story of the collection, ‘The Golden Rose’, has reached, if not old age, then late middle-age (curious how hard it is to guess the age of most of these characters – probably far younger than we think), happily single because to have married the man she loved would have been to risk her ‘poetry dwindling into prose’. This is no mindless drift into romantic fiction: Aunt Esse, aka Frances Towers, pins herself, her niece and the reader wittily to reality, when having explained to her niece, Emma, that the man’s wife had run away, ‘Not,’ she added hurriedly, ‘that it is a wise proceeding to fall in love with men whose wives have left them. Much better not.’ A practical piece of advice, but Aunt Essie, the slightly dotty, poor relation, kept at arm’s length by Emma’s ghastly stepmother, ‘who had come into our lives,’ says Emma, ‘fortuitously, bringing her own world with her and blowing out the one we knew like a soap bubble.’

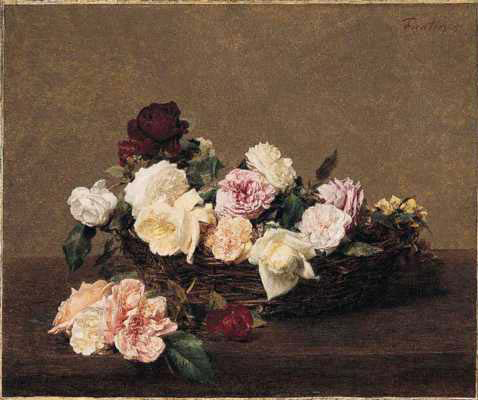

Emma recalls her own mother as ‘a light in the mind and a fragrance in the memory’. In her story it is the scent of roses that is evoked (roses abound in this collection, sniffed and plucked and stripped gently of their petals to explore their hearts) but also and as evocatively the scent of a tea chest lined with silver foil. Pleasant smells, flowers, wood ash and sandalwood and coffee beans, melting wax waft through the pages, along with some less pleasant, copying ink and gum, and others which not all of us might recognise: the smell of occultism? Are we to believe that the sense of smell is more powerful, more reliable than sight? Little Violet’s is certainly quite remarkable: Violet can smell secrets, but then Violet reads the cards. The supernatural is never far away. Only one of the stories in the collection is a true ghost story and yet there is something of the ghost story about almost every one.

These are beautifully structured stories, centred on individual families, and apart from an occasional venture to an office interior or a school, perhaps a short walk in a garden, contained within one or at most two houses. But we quickly learn, for the stories build on each other, not narratively but in mood, that a house is not necessarily a home, nor a family a place of love and warmth. There is little love remaining between husbands and wives, and children, mostly sisters, too often live ‘shut up in their private worlds, like grubs in their cocoons’.

Into each of these dysfunctional families, in some of which relationships are quite hard to discern, as though we had been thrown into a room and left to establish from a series of tiny clues who each person is, a slightly enigmatic figure is introduced, often disappearing as mysteriously as they arrived, but leaving change behind them. So subtle is the narrative that is hard to say exactly how the change has been brought about it, and even to be sure if it is change for the good or for the bad.

Comedy or tragedy? Wise and gentle Esse knew ‘that life can be terribly sad and utterly ridiculous, sometimes at the same moment’. That is what Frances Towers knows and what makes the stories in Tea with Mr Rochester so richly satisfying.