When Reuben Sachs was published in 1888, the Jewish World accused Amy Levy of ‘delighting in the task of persuading the general public that her own kith and kin are the most hideous types of vulgarity’. The Jewish Chronicle, which had published favourable notices of all Amy Levy’s previous works, did not review it. The Anglo-Jewish community at the time was already being challenged: a large number of Jews, fleeing the pogroms of Eastern Europe, were arriving in Britain, impoverished aliens who threatened the community’s position in society. Little surprise that Reuben Sachs should have stirred resentment. The last thing they needed was such a closely observed, cruelly critical portrait by one of their own.

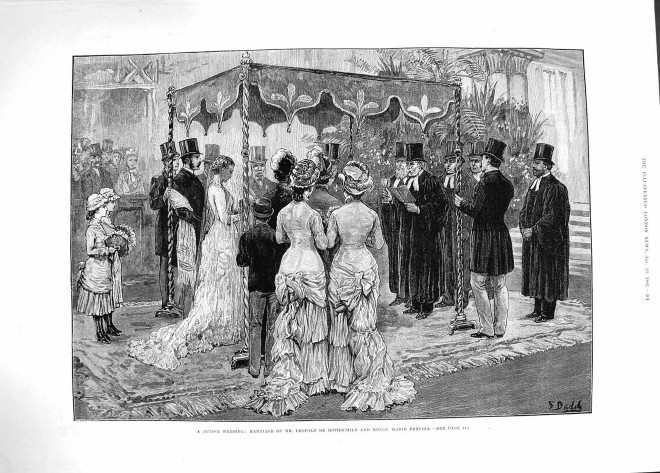

By the 1880s the most prominent Jewish families had, not without a struggle, become part of the establishment, indeed some, like the Rothschilds and the Sassoons were part of the Prince of Wales’ circle. Amy Levy’s Sachses, Leunigers, Quixanos, Montague Cohens are not in that league; but when old Solomon Sachs surveys his extended family, his assembled grand-children, he can look at them as young English men and women and revel particularly in the success of his grandson Reuben, whose rejection, after Cambridge, of a career in the Stock Exchange for one in the Law and a possible seat in parliament, represents ‘the summit of the old man’s ambitions’. Bearing in mind that Cambridge University did not admit Jews until 1871, that the first professing Jew was called to the bar in 1833 and the first Jewish MP did not take his seat until 1858, his pride is more than justified.

Anglo-Jewry, as Amy Levy knew it and painted it, rated worldly success in the Gentile sphere more highly than success in areas traditionally its own. At the same time, it required of its children that they remain spiritually (in the loosest sense, for many are barely pratiquant) within the Community. They both want and don’t want to assimilate. There is a tension at the heart of the Community, which Levy touches on time and again. It is most evident, and most comical – wit is her sharpest weapon – in the blatantly aspirational Montague Cohens, Reuben’s sister and brother-in-law, who stick rigidly to Jewish dietary laws, attend the conservative Bayswater synagogue, but crave introductions to Reuben’s English upper class friends, and will find themselves ready to forgive an unfortunate marriage, if it means invitations to the country houses of the titled.

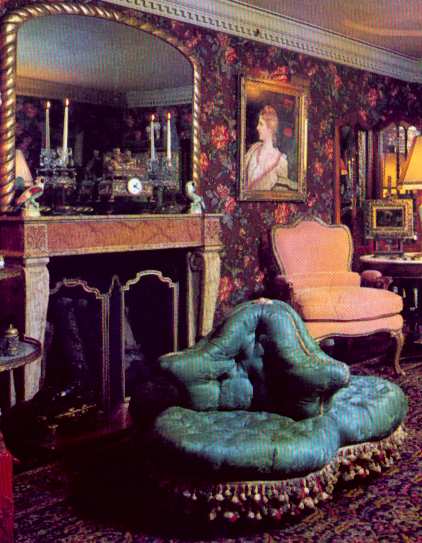

Focusing on five inter-related families, Amy Levy shows us the Community, in miniature. They live between Maida Vale and Hyde Park, no more than a short omnibus ride between them, the more prosperous closest to the Park, as the Levys did before a financial downturn drove them to Bloomsbury. The humblest house, belonging to the Quixanos, Sephardic Jews, the vieille noblesse of the Community (class distinctions are as marked and subtle and incomprehensible to outsiders as those of any community), is little and crowded, the richest are large and crowded – great, vulgar, over-decorated rooms, ugly, old-fashioned splendours. The deadening lack of any culture, chandeliers and jewels but no books – ‘Israel Leuniger regarded every shilling spent on books as pure extravagance’ – the claustrophobia is stifling.

Only in the final pages do we find Judith Quixano, newly married to her Gentile, Jewish convert, husband, in the ‘modern, fashionable drawing room’ of his flat, South of the Park, sitting by an open window; meanwhile her cousin Leo, walks under the shade of Cambridge lime trees.

Reuben Sachs is not autobiographical. The narrator may be voicing some of Amy Levy’s thoughts, but is a virtual character in the novel, on rare occasions appearing, as it were from behind a heavy curtain, an enigmatic character, an insider, another Jew perhaps, whose knowledge of the future suggests that she, or he – it is impossible to know, and perhaps there is more than one narrator – is looking back at the events described. No-one is flattered. Men and women alike are drawn in such a way that they resemble the widely published anti-Semitic caricatures of the period. The women, for the most part, are sallow, short and stout. Only Judith, the closest the novel gets to a heroine, stands out, literally. She is tall and regal looking, but her beauty is nevertheless of an ‘exotic nature’. The men are similarly unprepossessing. Reuben is, unusually, slim, but his figure is bad, ‘and his movements awkward, unmistakeably the figure and movements of a Jew’. His cousin, Leo Leuniger, is small and slight, but he shares the ‘graceless, characteristic walk’ and his ‘picturesque’ head is ‘of a marked tribal character’ and ‘too large for his small, slight figure’.

On first reading Reuben Sachs, lost in the extended families, I drew up a (very untidy) family tree. By chance, or maybe not, out on a limb, to each side, were Esther Kohnthal and Leo Leuniger, and, hanging loose from the body of their respective families, Lionel Sachs and Ernest Leuniger. Ernest, the eldest of his family, spends his days playing solitaire, unsuccessfully, and must be sent away with his ‘valet’ when his presence might be awkward. Lionel, the youngest of the Sachses, a neer-do-well, has, ‘with difficulty been relegated to an obscure colony’. (Amy Levy is a mistress of understatement). The Community, it seems, does not tolerate misfits. Esther’s father has been shut up in a madhouse for ten years, and even Reuben has been forced to recover from a nervous breakdown in the Antipodes.

Esther lives uneasily in the family home, in her own words ‘the biggest heiress and the ugliest woman in all Bayswater’, feuding with her mother and staying in bed with a romantic novel, on the Day of Atonement, when all of her relations, even the most secular, attend their various Synagogues. If Amy Levy has an alter ego in the novel, perhaps it is Esther. Levy was not rich, but she thought herself ugly, and knew herself to be abrupt and like Esther, prone to bursts of candour. Esther, is, in many ways the most consistent, and most consistently sympathetic character in the novel. Leo, about to enter his last year at Cambridge, is the freest spirit. Musical and academic, and a passionate country lover, he has escaped the Philistinism of his family, and the materialism of his race. His aunts and uncles consider him ‘stuck-up’.

Judith, who knows they are clever, reflects that ‘these two people had an uncomfortable, eccentric, undignified method of setting about things’. ‘They cry out against the gods’, and the utterly conventional Judith, has a quiet contempt for them. For even the good-looking, stately, calm Judith has feet of clay. The narrator who at one moment hymns her ‘her beauty, her intelligence, her power of feeling’, later damns her as a thorough going Philistine, a ‘conservative ingrain’, then describes her (only slight more gently) as a ‘touchingly ignorant and limited creature’. Our heroine, if such she is, is the daughter of a scholar, but owns only the books given to her by Reuben, for whom one of her attractions is that she is ‘teachable’. What a chilling word.

Cousin Rose is almost right when she says that Reuben is ‘hard as nails’. He is not heartless; he is in love with Judith, but that is no basis for marriage. ‘It isn’t everyone,’ Reuben explains to Leo, ‘that can afford to marry beggar-maids.’ Love and ambition are incompatible, and, though she may be teachable, Judith has no fortune. Without her childhood sweetheart, she is just one of ‘the vast crowd of girls, awaiting their promotion by marriage’, but dreading the dreary prospect of ‘life on the shelf’. Not only Jewish girls waited in that crowd, but for them the wait was more stressful, the field of suitable young men being narrowed by the addition of religion to the usual criteria of class and money. A Jewish girl needs a Jewish husband. Judith has no choice but to accept second best, a convert, whom she barely likes. But what of that? Her mother is neither surprised nor upset to hear that her daughter doesn’t like the man to whom she is engaged. Rose, her high-spirited and good-natured cousin, is equally phlegmatic, ‘we all have to marry the men we don’t care for. I shall, I know, although I have a lot of money’.

And what of the men, so often forgotten in woeful tales of Victorian couples? They, and Jewish men in particular, were expected to marry. Work will provide an escape, duty a moral crutch, but will they be any happier than their wives? What of Bertie Lee Harrison, the convert, a positively Wodehousian character, does he love Judith? She is his ticket into the Community, and, being a beggar in the marriage market, he hasn’t the luxury of choice. Will his plain cousin, Lady Geraldine, provide Leo’s ticket out? Given the choice, might he not have preferred to spend his life with his friend, her more handsome brother, Lord Norwood? For the Jew or the Gentile, in Nineteenth Century England, happiness was not the measure.

There is no doubt that Reuben Sachs presents a very unflattering picture of late nineteenth century middle and upper-middle class English Jews and does so in very acerbic, and frequently very witty way, with not a word wasted. But, if these Jews thrived in Victorian England, it was precisely because they shared the same values, the same materialism, the same belief in patriarchy. The Cambridge Review, noting that ‘a deep and bitter hostility to modern Judaism’ was central to the novel, added that Levy writes, for the most part, ‘with vitriol instead of ink’. Modern readers may ask themselves whether the targets of her vitriol are in fact much wider than her own “tribe”.

Quotes ….. do share your favourites

[Mrs Leuniger]’ stood dejectedly welcoming her guests. She was wearing a quantity of very valuable lace, very much crumpled and had a profusion of diamonds scattered about her person, but had apparently forgotten to do her hair.’

‘Meanwhile in London Bertie-Lee Harrison was celebrating the Feast of Tabernacles as best he could. He had given up with considerable reluctance his plan of living in a tent, the resources of his flat in Albert Hall Mansions not being able to meet the scheme,’

‘The practical, if not the theoretical teachings of her [Judith’s] life had been to treat as absurd any close strong feeling which had not its foundations in material interests. There must be no giving away of one’s self in friendship, in the pursuit of ideas, in charity, in a public cause. Only gushing fools did that …’

‘Aunt Ada, who all the days of her life had known wealth, splendour, importance, and as far as could be seen never enjoyed an hour’s happiness.’

‘When I was a little girl,’ cried Esther, still looking at her [Judith], ‘a little girl of eight years old, I wrote in my prayer-book: “Cursed art Thou, O Lord my God, Who has had the cruelty to make me a woman.” And I have gone on saying that prayer all my life – the only one.’

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

The Victorian Chaise-Longue by Marghanita Laski (Persephone Book No.6)

Consequences by E.M. Delafield (Persephone Book No.13)

The Making of a Marchioness byFrances Hodgson Burnett(Persephone Book No.29)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

‘This is a beautifully crafted little novel. The language is faultless, pared down to only that which is needed, yet at the same time painting an unforgetable picture of Anglo-Jewish life at the end of the 19th century. The story is that of Reuben Sachs and his cousin Judith Quixano. Much is expected of young Reuben, and Judith is a poor relation, and a romance between them would be unthinkable in the gossipy, snobbish community they live in. In terms of plot it might be fair to say that not much happens until then end of the novel, the families visit one another, go shopping, and there is a ball. Yet a world is created in such a way as the people that live in it step right off the page.’ good reads

‘In Reuben Sachs, Levy followed up on her 1886 critique of George Eliot by explicity satirizing the idealized depiction of Jews in Daniel Deronda, and, in doing so, rejected a way of representing Jewish life that had become one of the conventions for treating Jews available to the Victorian novelist, especially the Anglo-Jewish novelist. Dispensing with this convention allows her to raise the question of what it means to be a Jew and to probe the moral nature of the Anglo-Jewish community. highbeam