I began to write about Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day with some trepidation. I love it, who couldn’t love it? But I wanted to work out why it has lasted so well, why the ‘feel-good’ factor, which made it so popular in 1938, remains undimmed seventy years later. I was afraid that any attempt to analyse it would be like trying to deconstruct a soufflé.

There is nothing original in comparing Miss Pettigrew with Cinderella. One blogger describes Miss Pettigrew as a combination of Cinderella and Mary Poppins. I am inclined to agree. Thanks to a chance encounter with the exotically named Delysia LaFosse, Guinevere Pettigrew goes from rags to riches in twenty-four hours, while handing out no-nonsense advice along the way. The down-trodden, virtuous, ladylike Miss Pettigrew meets, Miss LaFosse, who is none of those things.

Twenty years, at most, divide the two, but they have grown up in different worlds. We glimpsed these worlds, and we met these women in last month’s Forum book, A Woman’s Place by Ruth Adam. Miss Pettigrew was already a ‘superfluous woman’ when she was born, perhaps around the turn of the century. By 1911 women outnumbered men in the population by nearly 1.5million. E.M. Delafield (author of Consequences, Persephone Book No 19) writes of her own pre 1914 girlhood that she ‘could never remember a time when she had not known that a woman’s failure or success in life depended entirely on whether or not she succeeded in getting a husband…. any husband at all was better than none.’ The tragedy of her heroine, Alex Clare, bears that out. By 1918 the statistics were far worse: 65 women to every 45 men.

If being on the shelf was bad, being poor and on the shelf was infinitely worse. A girl needed a roof over her head. If she had no husband to provide a roof, and her father lacked the means either to keep her under the family roof, or to educate her to a level at which she could pay for own roof (and very few would be able to afford that), domestic service at some level was one of the few choices open to her.. Miss Pettigrew, daughter of an impoverished vicar, has had to make her way as a nursery governess, not in a large aristocratic household, for there were fewer of those by 1920, but in a series – for she is not a very good nursery governess – of small middle class households, in which she has had to live tight up against the family, without ever being part of it, ‘living in other people’s houses and being dependent on their moods’. Deeply romantic at heart. Miss Pettigrew nevertheless readily admits to herself that she would have married any man who had asked her ‘to escape the Mrs Brummegans of this world’.

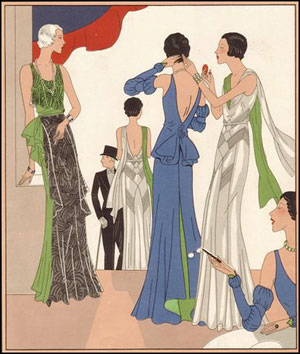

Miss Delysia LaFosse, has reached adulthood in the thirties, not a good time economically, but she does not want for suitors: the current trio, Phil and Nick and Michael, would have been at school, or in their prams, when their older cousins were dying in the trenches. Nor does she want for money. Miss LaFosse and her friends can look after themselves, and if singing or hairdressing doesn’t bring in enough, they can rely on their looks. Respectability is no longer everything. These are latter-day flappers, who have inherited the freedoms of the nineteen twenties, even if they are back in corsets. Miss LaFosse has learnt how to live by living. Miss Pettigrew has had to learn to survive by observing the lives of others.

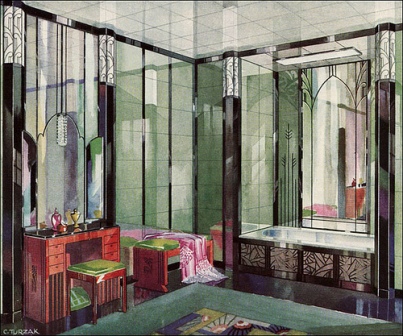

Ordinarily their paths would be unlikely to cross, but a fortuitous error on the part of an employment agency takes Miss Pettigrew over the threshold of 5 Onslow Mansions into a different universe. She leaves behind the rigid conventions instilled in her by her mother, recognising immediately that Miss LaFosse’s room was ‘not the kind of room my dear mother would have chosen’, but quickly sensing that it ‘was the kind of room in which one did things and strange events occurred and amazing creatures … lived vivid, exciting, hazardous lives.’ In this wonderland objects are brilliant, velvety, exotic, colourful. Nothing matches anything else (the late Mrs Pettigrew must have had views on matching) and when the door knocker sounds, it does not announce the butcher or the baker or the candlestick maker, but some new excitement, some new drama. ‘This,’ thought Miss Pettigrew, ‘is Life. I have never lived before.’

Miss Pettigrew arrives at Onslow Mansions in an ugly, threadbare brown coat, thin, hungry, timid, defeated and friendless, in the forlorn of hope of being taken on as a nursery governess. Miss LaFosse, golden haired, rosy cheeked and wearing nothing but a foamy negligee is expecting a new maid. Miss Pettigrew makes tentative efforts to explain herself, but is swept up in events, of which there is no shortage in Miss LaFosse’s rackety life. Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day is a classic comedy of manners, built on a case of mistaken identity.

The nursery governess casts her eye over the glittering room: unsuitable for children, ludicrously unsuitable, but she continues to believe, almost to the end of the novel, in the existence of her little charges. She takes the, invisible, lie-a-bed lover for one of them, while he assumes that any woman wide awake and dressed at ten in the morning must have been up all night, blissfully improbable. Time and again conversations are at cross-purposes. Miss Pettigrew soon stops minding, finding that the very oddness sends ‘thrills of delight down her spine’. And at least these strange people are talking to her. ‘Through years of endurance no-one had ever really talked to her.’ In occasional asides from the bubbling fun of the day, a picture emerges of a lonely, loveless life in the houses of others.

Her new acquaintances may be somewhat louche, and have pictures on the wall that are not quite decent; they may have too much bling about them; but they are warm and inclusive. She casts off her outdated social preconceptions, and pretensions. Phil ‘ was not a gentleman, yet there was something in his cheerful pleasantries that suddenly made her feel more comfortably happy and confident than all the polite, excluding courtesies that had been her measure from men all her life.’ Being a ‘lady’ has done her no good.

Working for the so-called ‘gentry’ has brought her no happiness. She could never satisfy her employers, but she has observed in them a range of behaviours on which to draw and against which to measure others. She has learnt from one that dry sherry is a safe alternative to a morning cocktail, from another that bland unawareness can defeat insults, from a third ‘she knew to a calculated nicety the demolishing effect of a negligent gesture’. These lessons will be put to good use in sorting out the complicated emotional affairs of her new friends.

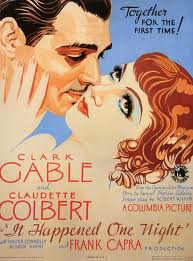

The world into which she has stepped is not wholly unfamiliar to her. Steeped in the novels of Ethel M. Dell, she knows ‘exactly’ what Miss LaFosse is feeling when Nick (lover number 2) looks into her eyes, ‘breathlessness, terror, ecstasy; a slow melting of all her senses towards trembling surrender’. Exactly. Thanks to the talkies, ‘her lone secret vice’, ‘her weekly orgy where for over two hours she lived in an enchanted world’, she knows a good looking man when she meets one: ‘a beautiful, cruel mouth, above which a small black moustache gave him a look of sophistication and a subtle air of degeneracy … something predatory in his expression …’. Precisely.

Minute by minute – the chapter headings delightfully register with absurd accuracy the passing of time – Miss Pettigrew slips further into her new identity. The joy of the day lies not only in her new surroundings, but in that, being taken for someone different, she becomes a different woman. Miss LaFosse takes her for someone she can rely on, and so she proves to be. Miss Pettigrew is resourceful, practical, not easily taken in, and she is used to dealing with children. These bright young things are just big children, who need a firm hand, and a good talking-to. Delysia needs a nursery governess as much as she needs a maid. More than either, Delysia LaFosse, née Sarah Grubb, needs a mother. Miss LaFosse plays Fairy Godmother to Miss Pettigrew, she dresses her, waves her hair, brings colour to her wan face; she takes her to the ball – the night-club – and finds her a prince. Her wish is that Miss Pettigrew should be that mother, a kind, sensible, loving mother who can put her life on a straighter path than she could have cut for herself. Both women have their wishes granted.

Winifred Watson, with the lightest of touches, paints the moment at which two worlds, one in which white powder is cocaine, and one in which it is a dose of Beecham’s Powders, collide, a collision from which springs humour, pathos, genuine emotion and, because this is after all a fairy tale, a positive outcome for all.

Quotes ….. do share your favourites

‘In all her lonely life Miss Pettigrew had never realised how lonely she had been … For years she had lived in other people’s houses and had never been an inmate in the sense of belonging and now, in a few short hours, she was serenely and blissfully at home. Â She was accepted. Â They talked to her.’

‘Simply and honestly she faced and confessed her abandonment of all the principles that had guided her through life. In one short day, at the first wink of temptation, she had not just fallen, but positively tumbled from grace.’

‘She could not deny that this way of sin, condemned by parents and principles, was a great deal more pleasant than the lonely path of virtue, and her morals had not withstood the test.’

‘She [Angela, Miss Pettigrew’s rival for Joe’s affection] had once heard that too much talking, too much laughing, too much animation, aged one. Apart from the primary consideration that she had never had anything to say, she meant to keep her looks.’

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Miss Ranskill Comes Home by Barbara Euphan Todd (Persephone Book No.46)

Lady Rose and Mrs Memmary by Ruby Ferguson (Persephone Book No.53)

Miss Buncle’s Book by D.E. Stevenson (Persephone Book No.81)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day was written in 1938 and is very much a product of its time, and is worth reading for that fact alone. The novel is a wonderful piece of escapism. The pace is swift and the novel races from one ridiculous situation to another. From the very first paragraph, which begins at 9:15 a.m, the reader is thrown into the action. Miss Pettigrew is compassionate and highly sympathetic, and you cannot help but warm to Delysia, who, despite being something of a ditz, is both kindhearted and generous. bfgb

As a character she’s so cleverly conflicted, between her strict and upright upbringing and the excitement and thrills of a wicked life. Her common sense is a breath of fresh air that you can’t help but fall in love with. I found myself chuckling more than once at her own wonder at finding herself in situations she’d only seen in the movies. SEEING people KISS? Shameful and almost too thrilling.

I want to hand this book to people I like, it’s so much fun. I just want them to give it back when they’re done. corinnesbookreviews