‘… my life has been a very ordinary one; no adventures, nothing dramatic, just the same sort of life as most of the women I meet in the street and think so dull.’ On the eve of her fortieth birthday, Helen Woodruffe looks back over her life, recording ‘the people and the places, and the choices and mistakes …’.

No need to apologise for spoilers: the outline is drawn in the first short chapter. Helen Woodruffe has lived for nine years in a street of ugly houses, with ugly gardens, which she barely notices and no longer minds. She is aware that her youth has gone, and does not mind that. Memories which she had been afraid to bring to the surface no longer have the power to hurt. ‘I do not mind about anything very much now, except, I suppose, John.’ John we take to be her son, and that ‘I suppose’ is so sad. Walter, in bed, asleep, spoken of without tenderness, must be her husband, but not the man she loved. Numb now to all emotion, she asks herself (and us) ‘if Hugo were alive still, would it be like this?’ Writing over a period of little more than twelve hours, sometimes at a hectic pace, at other times pausing to linger on the smallest detail, often in short, almost staccato, sentences, as though forcing herself to tell a story she can hardly bear, she occasionally lifts her pen and turn to speak directly to us, to explain, what she calls ‘the deadening’, how a life, once so full of joy, came to be hollowed out.

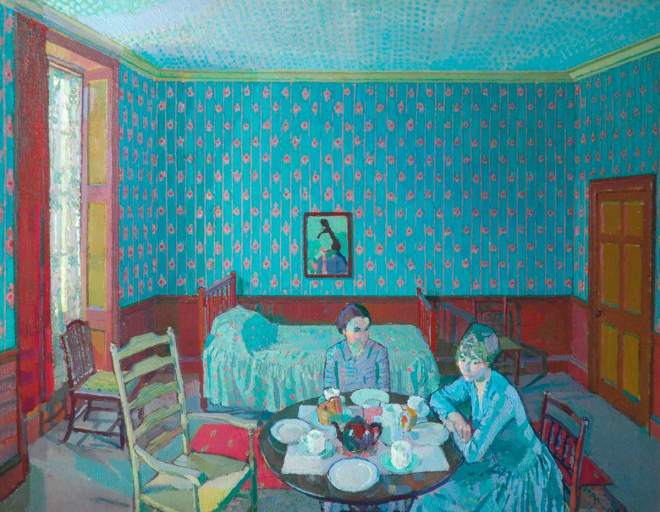

One person and one place stand out: Hugo, and Yearsly. Yearsly, a Queen Anne house, largely unchanged since the arrival of Helen and Hugo’s, great-grandmother in 1802, full of light and fine furniture, smelling of lavender and old polished floors, surrounded by gardens and woods and water, for which the term ‘spirit of place’ might have been coined, is the setting for Helen’s happy childhood. It is not her parents’ house: her father is dead, and her mother, an academic promoter of women’s causes, shows little interest in her for her first sixteen years, and none at all after she marries again and moves to Canada. The two ‘significant women’ in Helen’s life are her kindly Grandmother, who provides her London home, a comfortably large and elegant house on Campden Hill Square, and Cousin Delia, wife of her father’s cousin, chatelaine of Yearsly, where Helen spends the holidays in the glorious company of her second cousins, Guy Laurier, the golden youth, clever, handsome, strong and ambitious, and his younger brother, the more sensitive, more fragile, adored, less conventional, and more indulged Hugo.

Cousin Delia, with her half-smile and quiet grey eyes, never scolded, and never disapproved, generated ‘a kind of active peace and contentment’. Effectively orphaned, Helen’s childhood is close to idyllic: the rose garden, the Jasmine gate, the frog pond, and the Happy Tree, a spreading beech named by the children, outside, and for wet days, cardboard theatres, writing and illustrating stories, fresh milk and butter from the home-farm for tea, sent up by Mrs Jeyes, the cook. Still in the background, in the best upper-class tradition, is Nunky the boys’ nursemaid, who, later, will help Helen dress for her first ball, and, much later, for her wedding. Little wonder that it was the happiest part of her life. Little wonder that Guy’s wife later complains of the brothers and Helen, ‘you live in a world of your own, all long ago and out of date.’ And little wonder that Helen’s husband, Walter Sebright, an Oxford contemporary of the Lauriers (it would be wrong to call him a friend), should think ‘that we were all spoiled, that the realities of life were not brought before us, and that Guy and Hugo suffered afterwards for this.’

Walter had somehow attached himself to their charmed circle, first in Oxford and later in London, but without fitting, or indeed wanting to fit. Socially, intellectually, emotionally Walter is a world apart from the Lauriers, from Helen and from their delightful, and well-grounded, friends Mollie and George Addington, who Helen describes as having ‘a sort of solid nobility about them, a quality she concedes is lacking in her cousins and herself, and barely recognised by Walter. The Addingtons are shocked when Helen announces her engagement. ‘You and Hugo love each other far too well to marry other people,’ warns George. Of all the choices and mistakes in Helen’s life, Walter is the worst and most defining. And, when divorce was barely an option, inescapable.

She admits to not knowing Walter’s mind as she did Hugo’s. The two men ‘spoke different languages – or rather they used the same words for quite different meanings.’ He does not share her love of poetry or her interest in people; he asks nothing about her childhood, and dislikes talk of Yearsly, and she cannot begin to understand his preference for ancient Mycenean fragments over Greek vases. But Hugo is indecisive and impulsive and even those who love him best – and perhaps he has been loved too much – despair of his ever growing up. By comparison Walter seems strong, and wise. Somewhat touchingly he acknowledges that he is in many ways a dull fellow, and that Helen is ‘the other side of life’. He does love her, and for one fateful moment, she feels the wonder of being ‘wanted’. By the wrong man, with the wrong mother, a small, narrow-minded, bird-like widow, living in a tall dark house in Earl’s Court, full of dark furniture. If Walter is quite different from Hugo, Mrs Sebright is the very antithesis of Cousin Delia, and ‘He was devoted to his mother’, writes Helen, in a chilling one sentence paragraph.

Unusually for girls at the period, Helen had been under no pressure to marry. She had money of her own and knew she would have more when her grandmother died. Discouraged from going to university, she is nevertheless allowed a great deal of freedom, joining the Lauriers and the Addingtons for Oxford picnics without a chaperone, and going with them on walking holidays in Northumberland, to dances and theatres in London, riding in the park and punting on the Thames. She goes on holiday to Ireland with Mollie, who after Oxford takes a job in a laboratory and shares rooms with her brother in Chelsea. Her school-friend Sophia, passionate about Russian literature and politics, lives alone and writes. Helen goes to France and Germany, learns Italian, goes to lectures at Bedford College, and takes ballet lessons, happy to be alive, while wondering what to do. She is not without role models. But she, like Hugo, is indecisive.

While Helen drifted in marriage, the world was drifting towards war. This was the long hot summer of 1911, the focus of Juliet Nicolson’s book, The Perfect Summer, subtitled ‘Dancing into Shadow’. Helen and l her circle were indeed dancing into shadow, and barely one of them noticed.

Married life, if not exactly bliss, is contented, with daily afternoon outings, and tea – tea at home, tea with friends, tea in tea rooms … Her first forays into housekeeping are described in charming detail: trotting down the hill from their Hampstead house to the shops, learning the prices of things, making the breakfast coffee, buying books of French and Italian recipes – for the cook to try. Reminding herself when necessary that she can bear what thousands of other women have borne, pregnancy and childbirth, the tedium of household accounts, brown paint, mould on the bathroom walls, Helen is stalwart and strangely acquiescent.

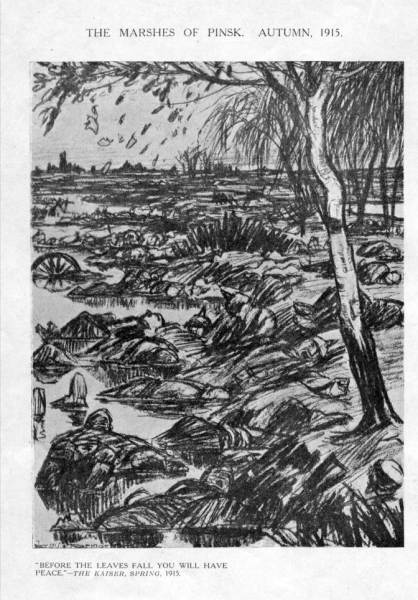

All together on the day of the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, astonishingly the Lauriers, the Addingtons, and the young Sebrights, barely know who he is – ‘Herzogovina, wasn’t it?’ Holidaying in Northumberland in the summer of 1914 with their little daughter, Helen and Walter are hardly more aware than William and Griselda (PB No. 1, William – an Englishman) of the immediacy of the threat. Rosalind Murray vividly describes their gradual realisation that war was coming, ‘that it would involve us personally, as individuals’, the way in which ‘the incredible changed somehow imperceptibly into the accepted, the taken for granted, state of existence.’ The young bride and mother, already beginning to struggle with domesticity finds herself facing far greater challenges. The servants leave to go into munitions, less satisfactory replacements are found, and then lost. Helen must shop, and clean, and mend, and care for her children at a time of rising prices, shortages and rationing. Catching sight of her face in a looking-glass she is shocked to see how the daily drudgery has aged her. ‘I was marking time, we were all marking time, waiting and waiting for the strain to relax, for the war to end; and meantime our youth was going.’

Helen – and Charlotte Mitchell, in her preface – indicates how closely the novel depicts Rosalind’s own life – while mourning the loss of the men she has loved, she must also confront the loss, less great, but just as final, of her own youth. She explains to Walter what it is that draws her cousin Guy to a bright young VAD: ‘You see, she is not lame, at all, in any way’. Unlike Diana, Helen is walking wounded. Non-combatants are also among the casualties of war..

Summing up her life, on the morning of her fortieth birthday, in the final sentence of the novel, she concludes that it does not seem very much, ‘I was happy when I was a child, and I married the wrong person, and someone I loved dearly was killed in the war … and that is all. And all those things must be true of thousands of people.’ But that is the very reason why The Happy Tree is such a marvellous read, both a delicate record of the ordinary, and a page-turner: not because of any urgency to know what happens – we know from the start – but because we want to know how and why, and what it has meant to Helen to stick to her pledge to Hugo to ‘hold out till the end’.