Is Dorothy Whipple too often dismissed by critics as ‘a woman’s writer’? The question was asked at a recent Persephone lunch. The obvious answer is ‘yes’, but then we ask, ‘why’? And who are these critics? And what is meant by ‘a woman’s writer’? And, why should it be somehow a term of derision?

Last week’s newspapers all carried the news of Philip Roth’s death. The ‘quality’ papers printed long obituaries. Though his most highly regarded novels feature his alter ego Nathan Zuckerman, and the novel that brought him first to the public eye had for anti-hero Alexander Portnoy a compulsive teenage masturbator, not one suggested that Roth might have been ‘a man’s writer’. All lamented the fact that he had been unfairly overlooked for the Nobel Prize (Roth apparently was of the same mind). Another Nobel refusé was his fellow American John Updike, whose Rabbit novels are currently being adapted for television. Fiercely rebutting accusations of misogyny on Updike’s part, the scriptwriter Andrew Davies nevertheless admits that ‘to redress the gender imbalance and address contemporary concerns’, extra scenes have been written in for Rabbit’s wife and mistress. At risk of sounding like ‘a shrill feminist’ (heaven forbid), is there not some contradiction here? If Updike had been so minded, he would have written the missing scenes – many male writers write wonderful women. Would any (male, because statistics make that considerably more than likely) critic presume to summarise Updike as a ‘man’s writer’? I am tempted to do so myself, and not in a good way.

In the Guardian in 2017 (in a piece which was reprinted in the last Persephone Biannually) the Irish novelist John Boyne describes attending a literary festival, ‘where a trio of established male writers were referred to in the programme as “giants of world literature”, while a panel of female writers of equal stature were described as “wonderful storytellers”. Even her most devoted fans would not be so bold as to call Dorothy Whipple a ‘giant of world literature’, but I warrant those three ‘male writers’ were no Titans, merely male.

Dorothy Whipple is a wonderful storyteller. She has absolute mastery of her material, her settings, her characters, and her plot, her control so delicate, her touch so light, that we are rarely conscious of an authorial voice, or hand. Because of the Lockwoods flows like her other novels so that we have the sensation of reading an assured, carefully paced account of events that have already happened. In her afterword to They Knew Mr Knight Terence Handley Macmath describes the ‘sense of order’ that characterises Whipple’s novels, which ‘are about wrongs being righted, people changing, sin being redeemed’ , but in which we cannot comfortably predict happy endings for all, nor can we know for sure who will be carrying the moral beacon. And so, we keep turning the pages, at times so eagerly that we miss the clues that Whipple has subtly planted, on which the plot and sub-plots will turn: the torn lining of a doctor’s bag, a pâtisserie owner unintentionally snubbed.

Because of the Lockwoods opens with a New Year’s Eve party. The Lockwoods are hosting the Hunters, somewhat ungraciously – ‘It would be one way of getting the food eaten up.’ We know the territory, a medium-sized northern town, where money and status are tightly bound, while not quite over-riding the more subtle distinctions of social class. Were it not for her wretched lack of funds, Mrs Hunter, the daughter of a doctor, and widow of an architect, would rank as the equal of the lawyer’s wife, Mrs Lockwood, rather than the abject recipient with her three children of turkey leftovers broken jellies, and ‘rather damaged bon-bons’ (that ‘rather’ is so ‘Whipple’), and cast-offs. Everything about the Lockwoods and their three daughters, exudes excess, and over-weaning self-confidence, while the Hunters appear forlorn. Mrs Hunter is ‘like a delicate plant drooping from lack of support’, her children left defenceless by the death of their father seven years earlier.

How quickly Mrs Lockwood damns herself out of her own mouth, as Dorothy Whipple moves seamlessly from her authorial voice to that of her character: ‘they should all come to Oakfield on New Year’s Eve, thought Mrs Lockwood benevolently. The children should take sweets home and perhaps she could hunt up a blouse for Mrs Hunter. The blue silk probably; she’d really had all the wear she could get out of it. Yes, Mrs Hunter could have that. They must all come and enjoy themselves.’ Enjoying it or not, Mrs Hunter feels beholden to the Lockwoods, to Mrs Lockwood for this occasional entrée into a social milieu of which she considers herself and her children to be members by birth, exiled only by monetary misfortune to life in an ugly little house, where they eschew all contact with their neighbours; to Mr William Lockwood for taking on the role of financial adviser after the death of her husband. ‘The fact that he had secretly profited, in one comparatively trifling matter, from so doing did not incline him to suffer her more gladly.’

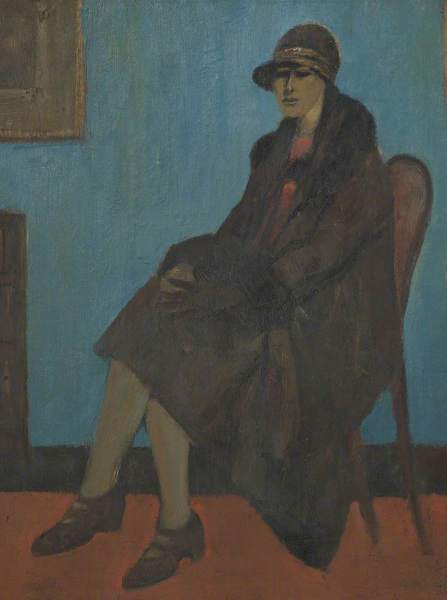

And there in one short chapter we have, dropped like a pin, the nub of the plot, and all but one of the principal characters. If there is a thread common to many of Whipple’s novels it is a lack of self-awareness in the worst of her women, and a lack of conscience in the worst of her men. We have spotted the villain – financiers in Dorothy Whipple’s world are rarely to be trusted, but William Lockwood has a redeeming feature: he is deeply attached to his children, and particularly to his youngest daughter. His wife is less obviously affectionate but ruthlessly competitive about her girls, and bursting with personal vanity, a bubble which Whipple, to our delight, is always keen to prick. Taking tea with Mrs Hunter: ‘Of course I have a very small foot,’ she would say, extending it for inspection. Thea inspected it. It was small and puffy; it was like a marshmallow.’ And hosting a charitable garden fête, ‘as she proceeded from table to table, bending in the tightly-fitting pink gown with the ospreys waving, Thea thought she looked like a boiled lobster walking on its tail.’ We hardly need telling that her bedroom slippers are pink and fluffy. If clothes make the man, they most certainly speak volumes about the woman. Do only women read these signs? Can men not understand the shorthand? Are such superficial details beneath them, or beyond them? Is it possible not to love Whipple’s description of the Lockwood twins dancing pumps whose soles ‘showed like two sponge -finger biscuits’? I suppose if you have never seen a pair of ballet pumps, or a sponge-finger …

‘Constance Hunter was not the sort of woman who stiffened to meet the blows of fate’, and the Hunters have found themselves relying on the counsel of a man who ‘had laid his strong, hairy hands to life and meant to wring from it the best of everything for his wife, his girls and himself.’ Her gratitude is craven and blind. He is willing to ‘help’ only because it would look bad if it got about that he’d refused – there are people above the Lockwoods in the social ladder whose approval might provide a leg-up – and his advice to the family as time goes on is cursory almost to the point of cruelty. Molly Hunter, a gentle girl whose one talent is for cooking, is forced at fifteen to take up a position as governess, a job to which she is wholly unsuited. Her brother’s hopes of becoming a doctor are dashed. Having been more or less auctioned off in Lockwood’s club – ‘anybody want a boy?’ – he must go to work in a bank.

Only Thea, the youngest of the Hunter children, the cleverest and the most determined, vows at the age of twelve not to do what the Lockwoods want: ‘If ever they want me to do a thing, that’ll be enough. I won’t do it.’ In her brilliant Preface, Harriet Evans rates her as possibly her favourite of Whipple’s heroines and it is hard not agree. She is certainly one of the most complex. Emerging comparatively slowly as the central character, pivotal to the interwoven plots, Thea is a fighter. Headstrong, often naïve, she is unimpressed by the Lockwoods, but has a strong streak of her mother’s snobbery. She is intelligent, reflective, perceived as secretive, and brave, a risk-taker, inclined to make powerful enemies.

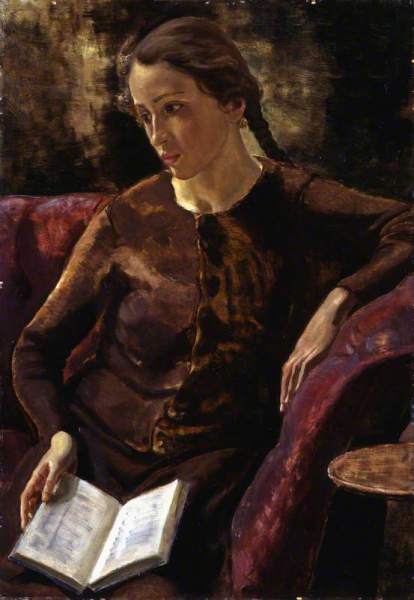

Dorothy Whipple writes rooms and their furniture with the same deftness as she writes clothes. The dark clutter of the front room at Byron Place, looking ‘so much like a collection of job lots that one almost looked for the sale tickets’, contrasts pitifully with the scented ease of Oakfield. Most evocative and atmospheric are the French interiors, in the glorious middle section of the novel. Thea has fought to join the Lockwood girls, and their grander friend Angela Harvey, for a year in a French pensionnat. One can smell the stark réfectoire with its oilskin cloths, and the cold classroom where all the windows were closed, ‘and the air was moted with chalk from the blackboards’. How perfect is DW’s coining of ‘moted’. The office of the Directrice is so small that to be at close quarter with her ‘was like being in a cage with a tiger.’ The attic room that Thea shares with Jeanne, another young teacher – she is not being ‘finished’ like the other English girls, but earning her keep, au pair – recalls Gwen John’s room in Paris, but far shabbier: ‘The wallpaper was cracked and faded pink … there was a strip of carpet beside each bed, there were two chairs, two small tables, one piled with books, the other presumably for herself.’ That we are seeing the room through Thea’s eyes is so subtly conveyed in the final clause. Her reaction to the house where she is engaged to give private lessons to Jacques Farnet and his sister, Simone, is similarly vivid: ‘… the formal salon with stiff, tasteless furniture on which were arranged cushions no bigger than handkerchief sachets.’ Could only a woman grasp the absurdity?

Thea is an innocent abroad. She recklessly defies French convention and walks alone through the little town, unaware of the many pairs of eyes that are turned on her. She fails to heed Jeanne’s words of warning about the Directrice, ‘Méfiez-vous de Mademoiselle Duchêne’. She is careful with Mme Farnet, ‘but she often forgot Simone, and it was a mistake to forget Simone.’ A rare authorial intervention, and a plot marker: Whipple flags it with the opening ‘But’ and the comma. Brilliant once again, and so easily missed. An unfortunate combination of bad judgement and bad luck brings the French idyll to an abrupt end.

Our delightful heroine must grow up. She must cure herself of ‘the malady of the ideal’, diagnosed in Thea by Jeanne, a little older, wiser, and resigned to a less than perfect life. Her guide is the initially despised neighbour, market stall-holder, self-made, and self-educated, Oliver Reade, the fictional hard-working brother-under-the-skin of Carrie the barmaid in They Knew Mr Knight and Miss Vanne the hairdresser in The Priory.

Thea, the young perfectionist, in her first conversation with Oliver, had scorned his market merchandise, rightly supposing it ‘to have flaws in it’, a scorn extending by implication to the seller himself. Many months later he had not been ashamed to admit in a letter that he had been doing rather well one way and another ‘mostly with things with flaws in them, but most of us have to be content with the things with flaws in them.’ It is a powerful message, and one to which Thea bends only after much pain, and broken dreams, but Oliver with his strong work ethic, honesty, and ambition tempered by realism, proves to be the Hunters’ saviour, the surprising bearer of the moral beacon, and a fully realised, delightfully human, character.

The title of John Boyne’s Guardian article was ‘Women are better novelists than men’. ‘My female friends,’ he writes, ‘seem to have a pretty good idea of what’s going on in men’s heads most of the time. My male friends, on the other hand, haven’t got a clue what’s going on in women’s.’ He puts it down to ‘the historically subservient role women have played in society that has made them understand human nature more clearly, a necessity if one is trying to create authentic characters.’ It’s hard to forgive him for not mentioning any Persephone writers, but perhaps that can be remedied. Starting with Dorothy Whipple?