Wilfred and Eileen opens in the summer of 1913. A group of undergraduates at the end of their final term gather in a room at Trinity College, Cambridge, looking forward to the May Ball, and full of optimism for their various futures. They can’t see the gathering clouds, but we can. Apologies for spoilers must surely be redundant. We can already guess that not all will still be alive in 1918, and that of those lucky enough to survive not all will do so unscathed.

Jonathan Smith has woven a vivid and moving novel from material passed to him by the ‘real’ Wilfred’s mother, material for a book which Wilfred Willett failed to get published, in spite of the best efforts of his wife Eileen Stenhouse. His many bird books were massively popular – British Birds published in 1950 was still in print when Wilfred died in 1961 – but his novels and memoirs never found an audience. Among pages of politico-philosophical writing, Swift spotted a jewel: an account of an unconventional love affair and a remarkable marriage embarked upon in the last months of peace and cruelly tested by the horrors of war.

Wilfred and Eileen are strong individuals, not anti-social but neither of them driven to conform. Only a trifle envious of those like his effortlessly charming friend David, who ‘seemed groomed for life, tailored to fit’, Wilfred considers himself to have outgrown the jocularity, and the scintillating brilliance of Cambridge. He is twenty-two and fiercely ambitious, burning to move on to the next stage of his planned trajectory. Wilfred is headed for the London Hospital, the largest general hospital in England at the time. He wants to be a doctor, not just any doctor, but ‘the greatest surgeon that charitable medical institution has produced.’

He is indeed a hard-working, utterly committed medical student, eager to learn from senior surgeons, a diligence that will in unexpected and unhappy circumstances prove to be life-saving. One year later, among the first volunteers for the London Rifle Brigade, he is determined to be the best officer in the regiment, and the best-loved, which is, although he is unaware of it, quite irritating for his fellow officers and almost equally so for the men serving under him. His attempts at proving himself above petty authority are construed as ostentation, and well-intentioned offers of help, such as carrying the packs of tired soldiers, gain in reward only ‘a subtle mixture of gratitude and distaste.’ Smith tells us that, had anyone told him this, he would have been shocked. ‘A deep vein of idealism ran through him.’

At Cambridge he had found the occasionally ribald nature of undergraduate wit not to his taste, and he is outraged by the coarse humour of his fellow medical students. Like many idealistic men, Wilfred, is to use an old-fashioned term, somewhat ‘un-clubbable’. Uninterested in conforming himself, or in conformity in others, he allows his May Ball invitee, fashionably dressed in pale rose and lavender, to dance away with one of his more worldly friends, and finds for himself the perfect partner in Eileen Stenhouse. He describes her to himself as the ‘sort of person to whom it would be fun to give a present’ – what a sweet and generous thought. Much later, when circumstances force him to rely on her firmness, her realises that this too had been part of her attraction that night in Cambridge. She is ‘taller than most girls’, and while there is nothing outré about her clothes, ‘she dressed if anything rather too casually people thought, without sufficient attention to detail and straightness of hemline – even safety pins had been seen in her dress. ‘ To the May Ball while others wear rose and lavender, she has a dress of cream and light brown, which she has been allowed by her mother to choose. What is unusual is not only the colour of her dress, but that she has chosen it herself.

At a time when a young man was almost as likely as a young woman to find himself under parental control, both moral and financial, breaking free was a risky venture. William sums up his situation, ‘She [Mrs Thumper] had been the proprietor for too long, he knew that now and his father would still be banker when he started at the hospital.’ Though both are of age, for William and Eileen to marry is an extraordinarily bold move, but, of course, delightfully ‘moral’. Much easier just to sleep together. The descriptions of their tentative love-making are full of delight, and never over-sentimental.

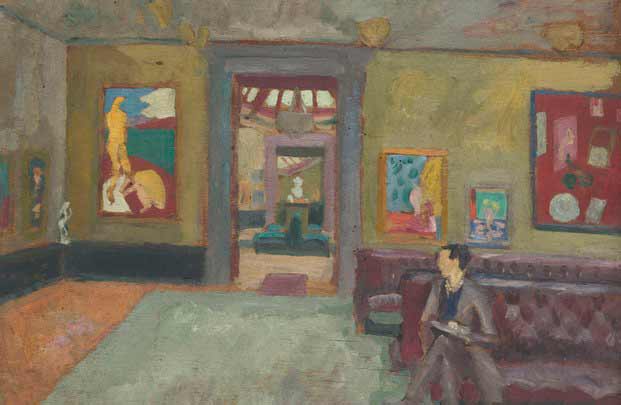

Wilfred’s knowledge of sex and women’s bodies has been acquired not from women of easier virtue than Eileen Stenhouse, but from attending a young mother in labour, an event which is described in graphic detail, though not quite as graphic as the operations at which he assists, where every cut and stitch is meticulously noted. A slice of medical history complements the political, social and cultural history. Wilfred reads in the newspapers about ‘the dreadful business in Sarajevo’. The Suffragettes are news, not history. He and Eileen discuss their views on art at the Second Impressionist Exhibition in 1913, and on music at the first English performance of Prince Igor. The reader is right there with them.

War, inevitably, comes and Wilfred, inevitably, leaves Britain for the front. He joins up with the London Rifle Brigade and arrives in France in October 1914. He was one of many thousands of men to do so: The British army before 1914 was tiny in comparison with other powers, with about 250,000 men serving. But the initial call for another 100,000 volunteers in August 1914 was far exceeded and almost half a million men enlisted in two months By the end of 1914 the British Expeditionary Force (as the first experienced troops came to be known) was essentially destroyed, losing 90,000 men in the first few months of war. The army was therefore increasingly reliant on those volunteers such as Wilfred who had had very little training.

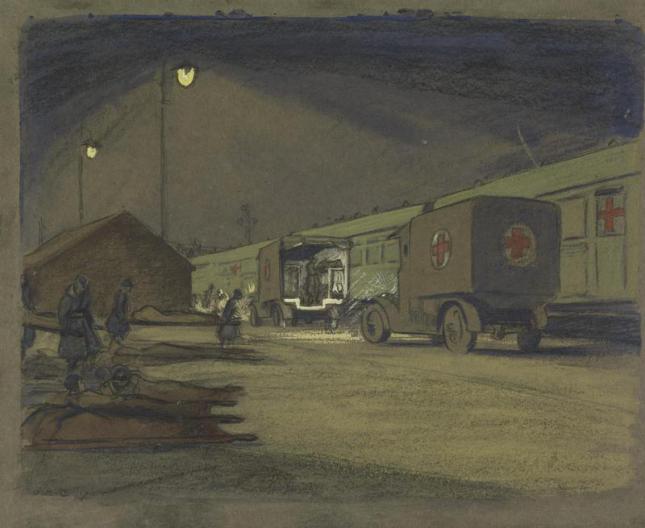

The casualties were horrendous and Wilfred will have been faced with attempting to treat injuries unseen during his time in Cambridge and London. Casualty Clearing Stations (CCS) were set up in tents away from the trenches for surgeries and amputations. Although traumatic, amputation saved the lives of many men as it often prevented infection. And infection was rife. Wilfred will have done his best with carbolic lotion to wash wounds and gauze soaked in solution. Severe wounds were smeared with ‘Bipp’ (bismuth iodoform paraffin paste).

We are with Wilfred most painfully in the trenches. The letters he writes home – it is hard not to believe that these are the real thing – are so credible, because the details are so ordinary: the loneliness, the cold, the distance of home and past, the joy of washing in clean water, ‘like going to the theatre’. ‘The only people who even know the enemy are there, out there for sure are the people who’ve been killed or wounded’ – is there a better description anywhere of the ‘fog of war’?

As with the first of Persephone’s First World War novels, indeed the first ever Persephone book, William – an Englishman, Wilfred and Eileen is both a ‘domestic novel’ (about engagements and weddings, family bickering and class expectations) and a ‘trench novel’, fully exposing the horrors of life on the front line. It starts as a seemingly simple Edwardian love story about two young people meeting and falling in love at University and beginning to set up home together: playing billiards on wet Sunday afternoons; Eileen watching Wilfred fish for supper when the weather is fine.

This privilege and promise is shattered by the violence of the trenches: the Great War comes and tests the courage of this young couple as it would have done for all the millions it affected. Reading it now we wonder about how brave we might have been in their situation. And what it really means to be brave at all.

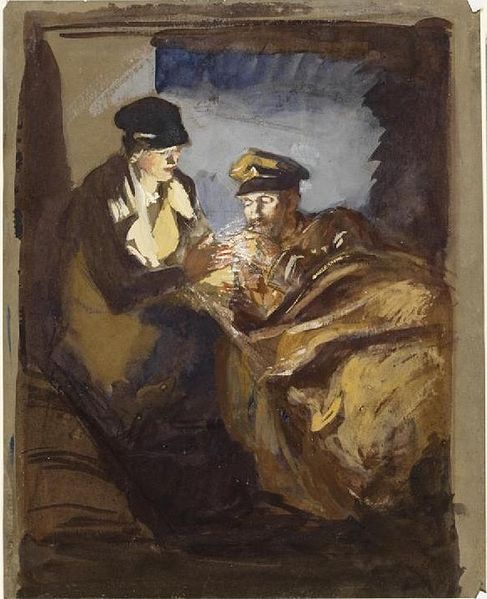

In his letters home Wilfred, the bold young doctor, describes divvying up the scarce rum rations to keep warm in an abandoned Belgian convent and endless marching: for 11 miles one day, 17 miles the next – with bruised feet and sopping wet uniforms. But Wilfred remains, in his letters, stoic. He takes pride in his efficient trench digging and all the physical demands of being at war; he is strong and healthy and determined. But, as Jonathan Smith writes in his new afterword to this edition, this is just as much Eileen’s story as Wilfred’s: ‘How could a woman of her conventional background be so assertive and tenacious and strong? I was overwhelmed by her extraordinary determination. In her refusal to be beaten she was in every way the equal of Wilfred.’

For the turning point of the novel is when we see the real mettle of Eileen Stenhouse. Her bravery goes far beyond the genteel pluck of a young middle-class newly-wed, she does something truly brave (fear not, no spoilers here). Thus this is a novel which wonderfully plays with our expectations of masculinity and, in fact, what it means to be a hero in a time of war. Both Wilfred and Eileen prove themselves to be truly heroic and utterly brave; they both make decisions which force them to confront incredibly dangerous situations.

Sensitively fleshing out the main characters, and teasingly introducing contemporary detail, Jonathan Smith has written a novel which reads almost like a biography of a fascinating and brave man who owed his life to a remarkable, original and outstandingly courageous woman.