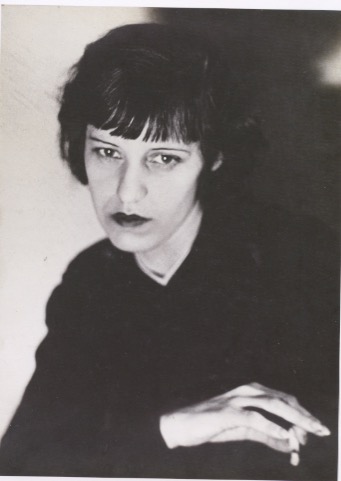

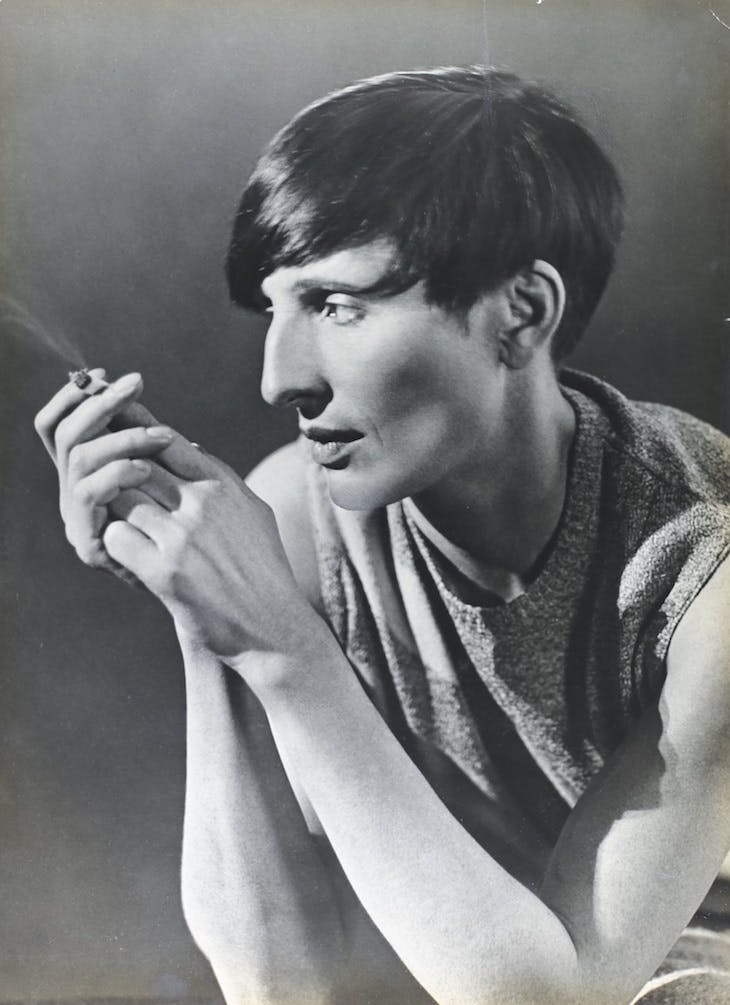

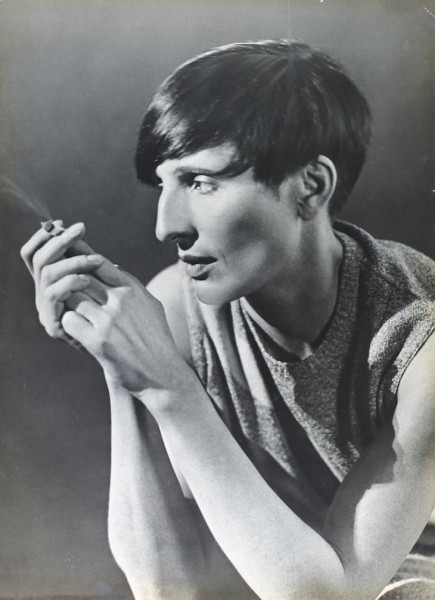

‘Why have we never heard of Dismorr and the other female modernists with whom she shared her brief moment in the sun?’ asked Rachel Spence in the Financial Times here. (Huh! We think we know why.) ‘The new show at Pallant House in Chichester remedies the neglect with a thorough, nuanced investigation into the art and politics — both in terms of gender and wider society — of early 20th-century British modernism. En route we discover not only Dismorr but a clutch of other outstanding, forgotten practitioners. Born in Gravesend in 1885, to a father who was an Australian sugar merchant, Dismorr grew up in a world where women’s lives oscillated between the confines of patriarchal tradition and new possibilities for liberation. On the one hand, they were still regarded as wives and mothers. (Wyndham Lewis once asked Dismorr to make tea for his guests at an artistic gathering.) Yet better education, allied to improved networks of travel and communications, meant Edwardian women were more informed and ambitious than their Victorian counterparts. The demand for women’s suffrage, which gathered pace as Dismorr matured, exemplified the progressive mood. Blessed with a private income, Dismorr enrolled at the Slade School of Art. In this ostensibly forward-looking institution, women were nevertheless obliged to study life drawing in a dark basement.’ This is Jessica Dismorr’s Les Baux, the Priest enters his Church (1911).

‘Why have we never heard of Dismorr and the other female modernists with whom she shared her brief moment in the sun?’ asked Rachel Spence in the Financial Times here. (Huh! We think we know why.) ‘The new show at Pallant House in Chichester remedies the neglect with a thorough, nuanced investigation into the art and politics — both in terms of gender and wider society — of early 20th-century British modernism. En route we discover not only Dismorr but a clutch of other outstanding, forgotten practitioners. Born in Gravesend in 1885, to a father who was an Australian sugar merchant, Dismorr grew up in a world where women’s lives oscillated between the confines of patriarchal tradition and new possibilities for liberation. On the one hand, they were still regarded as wives and mothers. (Wyndham Lewis once asked Dismorr to make tea for his guests at an artistic gathering.) Yet better education, allied to improved networks of travel and communications, meant Edwardian women were more informed and ambitious than their Victorian counterparts. The demand for women’s suffrage, which gathered pace as Dismorr matured, exemplified the progressive mood. Blessed with a private income, Dismorr enrolled at the Slade School of Art. In this ostensibly forward-looking institution, women were nevertheless obliged to study life drawing in a dark basement.’ This is Jessica Dismorr’s Les Baux, the Priest enters his Church (1911).

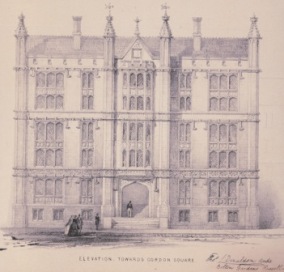

‘An artist at the forefront of the avant-garde in Britain – from her involvement with the Rhythm group during the late 1910s, to vorticism, post-war figuration and the abstraction of the 1930s – Jessica Dismorr (1885 – 1939) has since, unjustly, fallen into obscurity. But at the Pallant in Chichester there is an exhibition of the work of her and her contemporaries who engaged with modernist literature and radical politics through their art, including their contributions to campaigns for women’s suffrage and the anti-fascist organisations of the 1930s.’ This is Abstract Composition 1915. Jessica Dismorr said that the painting was inspired by nights she spent wandering London with its ‘precincts of stately urban houses. Moonlight carves them in purity . . . They are the children of colossal restraint.’

‘An artist at the forefront of the avant-garde in Britain – from her involvement with the Rhythm group during the late 1910s, to vorticism, post-war figuration and the abstraction of the 1930s – Jessica Dismorr (1885 – 1939) has since, unjustly, fallen into obscurity. But at the Pallant in Chichester there is an exhibition of the work of her and her contemporaries who engaged with modernist literature and radical politics through their art, including their contributions to campaigns for women’s suffrage and the anti-fascist organisations of the 1930s.’ This is Abstract Composition 1915. Jessica Dismorr said that the painting was inspired by nights she spent wandering London with its ‘precincts of stately urban houses. Moonlight carves them in purity . . . They are the children of colossal restraint.’