It is nearly summer, we have the shop door open, retreat in to the garden for the occasional sun bath, and here is one of the windowboxes.

We are all still in shock about the election although in Bloomsbury we have a wonderful new MP, Keir Starmer. We are going to invite him to tea and will keep you posted as to whether he comes or not. It was tears all round last Friday as we watched both Ed Miliband and Nick Clegg give their resignation speeches. Clegg’s remarks about fear and grievance gave us liberals a lot of food for thought as we realised that liberalism has become something apparently only the affluent can indulge in.

Here in the office we have been reading a very good book about domesticity and feminism. It is by Maureen Freely and is called What about Us? An open letter to the mothers feminism forgot. First of all there is ‘a depressing survey of the feminist literature on motherhood’ (her words) and the conclusion that ‘having a child is the fastest way of turning into a second-class citizen – and yet it is something that most women still want and actively choose.’ She then writes about possible responses to the ‘problem of feminist antipathy to maternity’ but declares that ‘you do not have to give up your feminist ideas in order to speak out in defence of parents, children and families.’ And yet ‘feminism is not for mothers, but for daughters’ – feminists are ‘too happy in those rooms of their own, too busy redefining their sexuality, having too much fun in their postmodern integrated circuits. While those of us who are bringing up families today are too stretched, too discouraged, too weighed down with our double loads even to dream of a way to attract their attention.’ The book is stimulating but a bit abstract. For example, it is only right at the end that she mentions possible practical solutions, like dovetailing school and office hours and so on. (My personal solution would be to have a traiteur – a place where you pick up ready-cooked food – on every corner.) But overall this is a stimulating and very thought-provoking book. And what on earth is the solution in the long run?

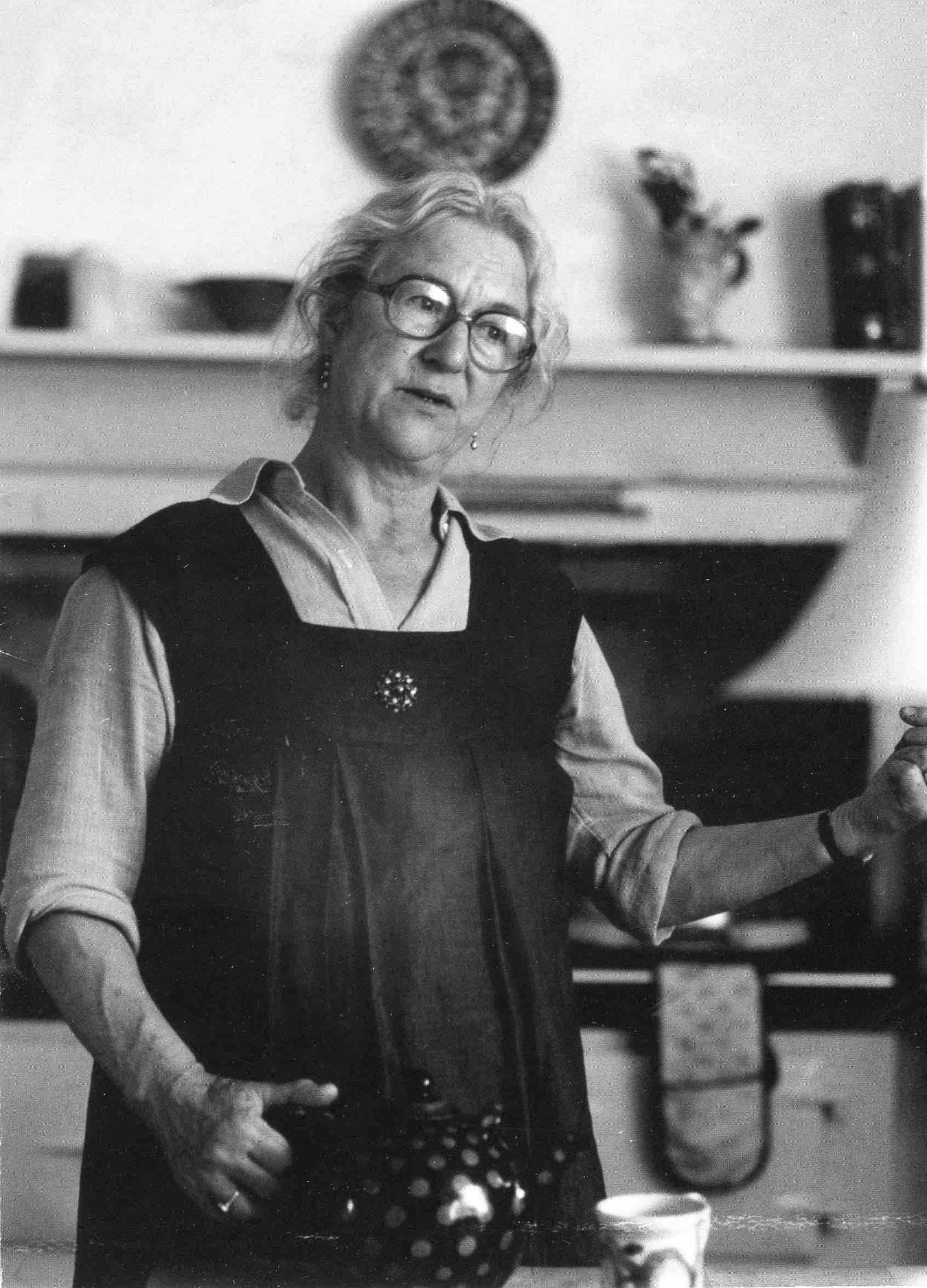

This week on the Post we have covered the subject of looted art. The final picture mentioned Anne Olivier Bell because, as Anne Popham, she was one of the Monuments Men.

Later in life she edited Virginia Woolf’s diaries. At the National Portrait Gallery last autumn her daughter Virginia Nicholson gave a very interesting talk about how her father Quentin Bell wrote the biography and her mother edited the diaries . This was recently reproduced in Canvas, the magazine that is sent to friends of Charleston Farmhouse.

It seems that Leonard Woolf ‘placed the diaries in the bank in Lewes for safe-keeping. But before doing so he had the entire diaires transcribed by a typist. He retained the top copies, but the carbon copies were scissored up and in 1953 Leonard published that chopped-out selection as A Writer’s Diary (now Persephone Books No. 98).

‘In 1966 Leonard packed the carbon copy remnants into manila envelopes and dispatched them to Quentin in Leeds. He told him that – since the missing sections had been published – he had only to reconstitute the published with the unpublished sections, and the result would be the whil Diary from 1915 until Virginia’s death in 1941. Simple’.

It was Mrs Bell, Anne Olivier (always known as Olivier) who then ‘began meticulously piecing together the ticker-tape jigsaw puzzle of Virginia’s cut-up Diaries. For the duration, her raw material was a patch-together done with scissors and Bostik.’

‘Next, Olivier began to compile what we would now call a research database. First, she got a Lewes printing company to print five sets of coloured cards, each one represting a month, with thirty-one ruled lines, and spaces to insert date headings. Then she put the month cards in chronological order in an open box beside her desk, with divider tabs for the fifty-seven years of Virginia Woolf’s life. On these cards information from the many and various sources was inserted day by day. White cards were used for information Leonard’s appointment diaries. Pink cards, meanwhile contained information gathered from letters between other people, referring to Virginia’s doings.

‘Alongside this Olivier developed another card index – an alphabetical catalogue of everyone Virginia Woolf had eer named in her diary or letters, with brief but scrupulously legible biographical notes on the roles.’

Later the Bells ‘procured scrolls of paper on which, with endless care and innumerable rubbings-out, they constructed and pieced together the Stephen family genealogy back to the early eighteenth century. Later that autumn of 1971 they laid out painted letters from A to Z, snipped up the galley proofs, and created a huge living index the length of the dining-room floor.

‘One day a collection of enormous cardboard boxes, strapped together with parcel tape, were delivered to our house. They contained the photocopies of the 2317 pages of manuscript of Virginia Woolf’s twenty-seven volumes of Diaries, shipped from the Berg Library in New York., and piled in a mountain by the front door. This was the raw material for the work which would take Olivier the next twenty years of her life.’

But ‘the transcripts that Olivier had pieced together didn’t always match the photocopied manuscript. Often they overlooked whole sentences…. Nothing escaped Olivier’s eagle eyes: compressions, abbreviations, slips of the pen, minor illegibilities, ampersands.

‘Her watchwords , drawing-pinned to the window frame above her desk, were ACCURACY, RELEVANCE, CONCISION, INTEREST.’

Olivier Bell wrote her own account of this process in a little pamphlet called On Editing Virginia Woolf’s Diary in 1989, copies (expensive alas) are available here.

Finally, another great woman, Hilda Bernstein, would have been 100 yesterday.

Nicola Beauman

59 Lambs Conduit Street