On the night of 8th May 1945, when bonfires were being lit all over England and men and women, soldiers and civilians, were dancing in the streets, Mathilde Wolff-Mönckeberg in Hamburg was in a more reflective mood, welcoming peace and the end of Nazi rule, deeply saddened by the loss of Germany; hating the thought of ‘her’ city being occupied by the British, but profoundly relieved that there would not be Russian soldiers in the streets. A four day curfew had been declared on 3rd May, and on the 6th Mathilde and her husband Emil Wolff, always referred to as Wolff, or W, Professor of English at Hamburg University, marked the end of the war by bringing up from the cellar things which had for six years been stored for safe-keeping, clothes and furniture, letters and photographs to be dusted down and returned to their pre-war places.

Not quite the celebration that Vere Hodgson (Few Eggs and No Oranges: Persephone Book No 9) was enjoying with her friends and neighbours, and yet, thanks to the BBC, the Wolffs were able to hear perhaps the very same thanksgiving service from St Paul’s in London, and Mathilde was able to imagine that she could pick out the voice of her youngest daughter Ruth. It would be another eighteen months before they met, for the first time since December 1938. The worst of the war for Mathilde was the enforced separation from four of her five children. Ruth and her husband, Ifor Evans, in Wales; Thys and his English wife in the United States; Jella and her Jewish husband in Sweden; and her oldest son Jan with (or possibly without) his Argentinian wife in Ecuador. Only her daughter Jacoba, with her husband Gustav, both doctors, and their son Fritz, five years old at the start of the war, remained in Hamburg with their mother and step-father (Emil Wolff was Mathilde’s second husband; the children’s father a Dutch art historian was still alive, but pretty much estranged). Letters abroad were first censored and then forbidden, and even communication with Jacoba, when she moved away from Hamburg, was often possible only by hand-delivered notes.

Mathilde’s wartime letters to her children were kept, and later hidden, for the duration in a large envelope. They were never sent or even shown to her children, and were not discovered until 1974, sixteen years after her death and almost thirty years after she put in the ‘final full stop’ in January 1946. We can only speculate as to whether Mathilde ever re-read this vivid, detailed and distressing record of the war years, an intermittent diary addressed to her children as a way of holding them close when they were far away, and keeping open, if only in her mind, a channel of communication. How different things were for Vere Hodgson, who was able to circulate her diary entries to friends and relations, one as far away as Rhodesia (although some letters were returned by the censor).

The worst months of the War in Britain were between September 1940 and May 1941. Over the course of 267 days 40,000 civilians were killed, about half of those in London. In the last week of July 1943, 45,000 civilians died in Hamburg as a result of British bombing, and hundreds of thousands of dwellings were destroyed. Mollie Panter-Downes in London War Notes (Persephone Book No. 111), implicitly critical of ‘the frankly jubilant way in which the press whoops about the tonnage of bombs that has been dumped on German cities’ (photographs of the damage would not be widely published until the following year), accepts that ‘German propaganda wails about terror raiding can’t be expected to make much impression on Londoners, not to mention the inhabitants of Coventry, Hull, Plymouth and other English cities which got hell in the days when the Nazis seemed to be the only boys who could dish it out’, while crediting the ‘average man’ with sufficient empathy to wince ‘over the gruesome thought that the Dortmund bombing [May 1943] must have made his own blitz night seem almost like a party.’ Only the more than averagely empathetic or imaginative might have wished they had tempered their initial delight: on 31st January 1943 Mollie had informed the readers of the New Yorker that ‘The daylight raids on Berlin were a fine tonic to Londoners’. The jury of historians is still out as to whether ‘area bombing’ succeeded in reducing the morale of German civilians, and even if it did, whether it was morally justified.

What is not in doubt is that with the exception of a small number of clergymen, and a few outspoken pacifists, including Vera Brittain, whose short book Seeds of Chaos: What Mass Bombing Really Means provoked wide and vituperative reaction on both sides of the Atlantic, it certainly raised the morale of the British. Vere Hodgson’s diary entry for 26th April 1942 reads: ‘We are all heartened by the terrible raids on Lubeck’, while Mathilde Wolff-Mönckeberg was writing, ‘The unhappy towns of Lubeck and Rostock have had devastating air-raids and huge areas were razed to the ground’. And on Sunday 15th August 1943 Vere Hodgson describes lying bed listening to ‘the Deep Purr’ of our bombers winging their way to Hamburg. She found it ‘a comfortable feeling.’ The bombers whose purr lulled her to sleep were about to drop their deadly load on Mathilde’s city. But Vere was not a cruel woman. In a previous entry she had written, ‘it is no satisfaction to hear of the treasures of our enemies being laid waste in a similar way [to those of the United Kingdom]. I don’t wish it.’

As ‘defeatism’ was a capital offence in Nazi Germany, few would have openly admitted to a lowering of morale. Mathilde had every reason to be hiding her ‘letters’. From the beginning she deplores ‘the Führer’s blind lust for conquest’, and, worse still, ‘the fact that nobody, not even those who opposed the régime most vehemently stood up against this.’ Even more dangerous, had her ‘letters’ been discovered would have been her declaration in June 1942: ‘It is not true what the newspapers reiterate, that the German people stand steadfastly behind the Führer’, and later, ‘Practically everyone knows that all that bluff and rubbish printed in the newspapers and blazoned out on the wireless is hollow nonsense, and when big speeches are made nobody listens any more.’

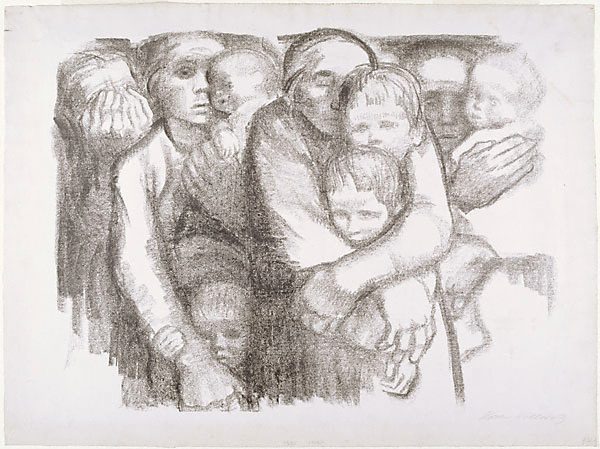

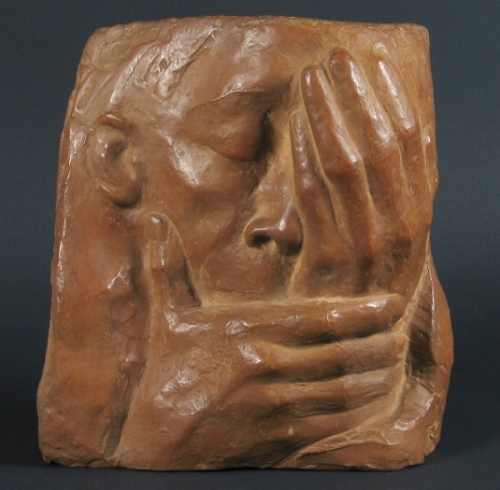

German successes are recorded with little elation, ‘We do seem to advance amazingly quickly, and the French are just running away from us. The famous Maginot Line was penetrated from the word go.’ When the first British bombers appear in the sky pursued by arcing searchlights, shot at by anti-aircraft guns, her sympathies are with hunter and hunted alike: ‘… those cruelly searching fingers of light remorselessly pick out and pounce on a small black dot, trying to tear it down, regardless of how many mothers, wives, brides, sisters and children will weep.’

Weep and struggle against worsening odds to maintain something approaching normal life: like women in Britain (and throughout war-torn Europe) women in Germany would queue for hours, stretch increasingly meagre rations, nightly carry what they could to air-raid shelters, improvise when supplies of gas or electricity or water failed, make do and mend. And do all of these things while, in the words of an elderly acquaintance to whom I spoke when writing about Few Eggs, ‘absolutely blindingly tired’. Mathilde’s letters are in many respects a mirror image of Vere Hodgson’s diaries.

Mathilde writes more, and movingly, about the bigger picture:

If one could look down from the sky onto the world, all one would see would be a circle of fire right round the earth … In all the cities, wherever they might be, right up in the icy north, in the hottest south, in snow-covered Russia, everywhere weeping, deserted women, mothers, sisters, fiancées, everywhere field hospitals full of mutilated young bodies.

She vividly describes the widespread lassitude, a lethargy among civilians that goes far deeper than tiredness, ‘…one even gets used to being half throttled; what at first appeared to be unbearable, becomes easier to tolerate; hate and desperation are diluted with time.’ This is far from the familiar up-beat celebration of wartime spirit that, correctly or incorrectly, characterised the British home-front.

But existential despair can swiftly be displaced by the search for a lost pen, irritation at a pair of broken spectacles, or the longing for a decent dinner. Food, the lack of, looms large in in the thoughts of both women: a marketing or bartering success can raise the spirits as much as a military victory. Mathilde trades the Wolff family dining table for fat and meat ‘and quite a number of other delicacies’. This is not the time for sentiment, ‘What else can one do these days? The stomach demands its due and money does not buy a thing.’ Vere Hodgson manages to spend her points on some stewing steak, dispelling further concern about the Japanese advance on Manila. Seemingly trivial shortages take on unexpected importance. Vere Hodgson’s need for a colander, Mathilde’s for paper serviettes. Welcome gifts from English visitors in the winter of 1945 (shortages did not end with the war) included shoe-laces, chocolate, and a comb!

Consolation in Hamburg, as in London, was to be found in music, in concert halls, on the wireless and on gramophones. Mathilde, W. and their friends celebrate Christmas 1944, gathered around the fire listening to Bach’s Christmas Oratorio. The same unexpected camaraderie of the shelter develops, and the same, equally unexpected nostalgia for it with the coming of peace. Books too bring comfort, poetry and novels – the irony of reading Trollope and Fielding aloud in their flat with W, the children’s old nanny, and Mathilde’s aged aunt is not lost on Mathilde, nor is W’s dogged effort in to continue his lectures on England in whatever venue he can find.

Only at the end of the war does this devoted anglophile find his faith challenged. Welcome as the British trucks are in May (for months Mathilde had been dreading that the Russians might reach Hamburg first) W. deplores the arrogance of the occupying soldiers, initially friendly but rapidly placed under orders from Montgomery not to fraternise with the German population, who were to be reminded not only that they had been defeated but that their nation was guilty of beginning the war. ‘Who,’ asks W, ‘destroyed our beautiful cities, regardless of human life and women and children, or old people?’

Mathilde’s summing up is qualified and more tragic. ‘Our beautiful and proud Germany has been crushed … millions sacrificed their lives and all our lovely towns and art treasures were destroyed and all this because of one man who had a lunatic vision of being “chosen by God”. The tragedy for Mathilde and W and millions like them was that, though they had endured the devastation of war living under a régime that they abhorred, they cannot escape what she calls ‘this collective guilt’. She defends their own position: they had, at some risk, supported their Jewish friends, but more active protest would have cost them their lives, or delivered them to the concentration camps. Early in the letters she admits to being ashamed to have stood by and said nothing, confesses to blushing with embarrassment at the treatment meted out to Jews in Hamburg, historically a liberal, tolerant city, adding that there are things which she recoils from describing, ‘much, much worse things’: is it knowledge of the horror, or fear of reprisal that stays her pen? Her words certainly raise the question of how much was known in Germany about the camps, and when. According to Mollie Panter-Downes, although the first photographs were not seen in Britain until April 1944, some liberal British journals had been publishing accounts of the concentration camps as early as 1933.

On the Other Side is a slim book – some sixty letters, none more than five or six pages, some little more than a page long, together with a Preface and a most touching Afterword by Mathilde’s daughter Ruth, and an illuminating historical afterword by Christopher Beauman. The raw reality of life, and death, on the German home-front, as it was lived and felt by a couple of thoughtful, liberal academics in their sixties is brilliantly conveyed on every page. Mathilde Wolff-Mönckeberg emerges as a brave, forbearing and generous, but never smug, or self-pitying woman; sometimes impatient, not above stealing a little extra jam from the family jar from time to time; capable of describing the destruction of her own cities, while regretting the damage done to those of the ‘enemy’, of confronting questions of responsibility and guilt. Above all we see a mother and grandmother, desperately missing her children and grandchildren, and sharing the pain of all women in times of war.