Several of these collected stories feature doors and many of them are closed. Outside lies freedom, but also loneliness and exclusion while, to be shut in can seem like imprisonment. The houses in The Closed Door are rarely homes and the sound of the front door being pulled to rarely heralds security, warmth or comfort. Doors are closed to keep others out rather than to celebrate the togetherness of marriage or family.

The Closed Door brings together ten short stories (actually two novellas and eight short stories) written over nearly thirty years. The viewpoint and the voices change – from the smug husband, to the desperately sad divorced wife, and the innocent child, Dorothy Whipple is pitch perfect – but the underlying themes do not. Whipple uses these small canvases to paint small lives, lived mostly by people with small minds, and shrivelled hearts. Marriages have grown cold, if they were ever warm, families barely function, love is a risky adventure, particularly for women.

There is little to admire about the men in these stories, although some expect admiration, one for writing the occasional article, another for, cynically, doing the ‘right thing’ by his pre-war sweetheart. Living comfortably on his (admiring) wife’s income, Ernest Hart does not doubt that his limited literary endeavours place him above other men and fully justify his cosseted position in the home (The Closed Door). Harry Smith’s ‘admirable’ loyalty to Meg – admirable because of her tragically brief fling with an American airman – allows his own infidelity (and we strongly suspect there will be more, why not?) to go unsuspected and unpunished (Cover). William West is a vain man, in whose eyes his ageing wife’s plainness and lamentable clothes sense, more than justify his affair with a younger, better dressed woman (The Handbag). William is, unexpectedly but gloriously, caught out.

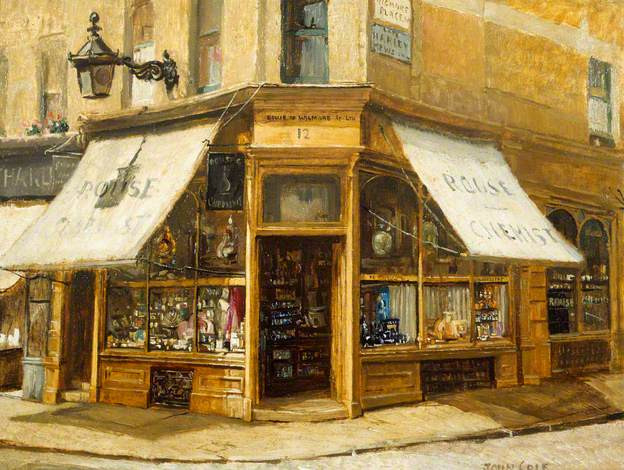

Respectability is what matters to Mr Parker, town chemist, arch snob and craven admirer of his upper class customers and neighbours, and when that is threatened by his only daughter’s bid for freedom, what can he do but pull down the blinds and bolt the door (Family Crisis)? Mr Bulford (Wednesday) has cruelly engineered grounds for divorcing his wife, depriving her of her children and replacing her with a new, younger, prettier Mrs Bulford. The first Mrs Bulford is touchingly philosophical, asking ‘since nature discriminates against women, why should men do otherwise?’ Do we hear Dorothy Whipple sighing here? In the happiest of families men could expect to be favoured: ‘Our parents travelled in the next compartment. In those days fathers were not disturbed.’ (Summer Holiday). Even Stella Hart’s good-natured husband lacks the imagination to protect her from her mother, being ‘rather apt to think that kindness solves all human problems, but of course it does not.’ Whipple’s’s voice again.

Women too can be socially aspirational, controlling, even cruel. Wanting a smart house and a smart husband, with which to impress the neighbours, though they have no car, Elsie Smith would prefer a garage to a greenhouse.

Alice Hart is a cold mother to baby Stella, an unexpected, unwanted and expensive arrival, ‘grimly determined to do her duty by the child who slept lightly in the cheap cot beside her’ – how brilliantly Whipple chooses every word. Alice’s thrift went beyond the choice of cot: to allow for growth she made bonnets that were too big, ‘but Stella never caught up with the bonnets’, which regularly obscured her view of the trees under which her pram was placed whatever the weather. Whipple permits a sad humour to break through from time to time, while maintaining her rage. Alice has no redeeming features. Her cruelty is bounded only by a careful regard for convention. ‘One thinks, romantically, that women to be fatal must be beautiful like Helen or Troy or the Egyptian Cleopatra; but plain, harsh, mean women like Alice Hart are fatal. They destroy as surely, but without the ecstasy that perhaps makes the ultimate destruction worth while.’

There are several unmarried daughters, and one niece, in this collection: their fate is not a happy one and only chance or exceptional courage gets some, but not all through the ‘closed door’. For the sake of economy Stella is forced into the role of unpaid servant; the housework falls to Margaret Parker, when her electively invalid mother chooses to swap her apron for a bed-jacket. ‘Mrs Berry was devoted to the care of herself and she expected the same devotion from Christine’; Christine Berry (After Tea) is another maid-of-all-work. Miss Morley (Youth) has money enough not to need an unpaid servant, but having trusted that her orphaned niece, taken in as a child, would be a companion for life, is shocked to the core when she defies her. Apart from Stella, these girls are victims of selfishness rather than active unkindness, victims too of a system that far from helping them to challenge their situation seemed to sanction it. The few who break free do so by embracing independence, not by following their hearts. Sexual, or simply romantic attraction leads more often to disaster than to bliss. Marriages in The Closed Door are for the most part loveless, often lonely and in their various ways unhappy.

These are sad stories, brilliantly told, perfectly paced, and with a comic touch that is occasional and easily missed. In the shortest of stories Dorothy Whipple can linger eloquently over the smallest detail, while in the longest big events are announced quite baldly, and back history conveyed in the slightest of hints. ‘It was one of the grudges he secretly bore his wife, that she took no notice of his tomatoes’ (Family Crisis) – how many more grudges the ludicrously self-important Mr Parker secretly bore, or what they were we do not learn, nor whether they were of greater or lesser magnitude than Mrs P’s failure to notice the tomatoes. We hear that same pompous inner voice a few pages later, in another silent altercation with his wife – no-one spoke much in the house – ‘He wished he wasn’t a man of high principles, because he longed to hit her.’ But Whipple is not entirely unsympathetic: ‘It did not exactly occur to Mr Parker that he was reaping as had sown. Few of us get as far as that.’ Her authorial interjections are rare but wise.

Parker is a complex character and well developed, but Whipple creates vivid walk-on parts: heavy, friendless Beryl, whose ‘deepest joy was to play the violin when her family was out of the house’ (The Closed Door), Mrs Bulford’s confused children (Wednesday), Rose, the young and pretty nursemaid, her admirer Frank, and her seducer the flashy Mr Salter (Summer Holiday) all live with many others on the page.

A treat for lovers of Dorothy Whipple and a marvellous introduction for those who are new to her.