Between August 1908, when she left New Zealand permanently for Europe, and January 1923 when she died, Katherine Mansfield lived at more than thirty addresses, rooms, flats, cottages, houses, hotels, and occasionally clinics. Move number twelve was to Clovelly Mansions in Grays Inn Road in April 1911, and it was here, a year later, that her life with John Middleton Murry began.

Not long after her burial at Avon-Fontainebleau in the winter of 1923, Katherine Mansfield’s coffin was moved into the communal part of the cemetery. Her husband, Middleton Murry, having commissioned a stone on which his name features prominently, and already receiving royalties from her posthumously published stories, while putting together more of her work for future publication, had failed to pay the fee required for an individual plot. ‘Even in death,’ writes her biographer, Kathleen Jones, ‘Katherine is not allowed to remain in one place.’

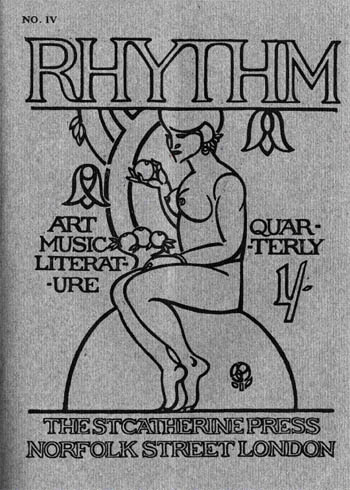

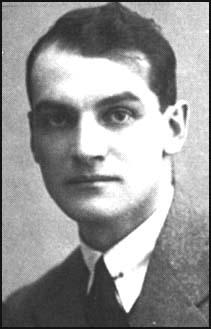

Katherine first met Middleton Murray in December 1911. He was twenty-two, a few months younger than her, still at Oxford, and already editing the literary magazine Rhythm. She urged him to leave Oxford, offering him a room in her flat, and before long a place in her bed. A bold move for a young woman in 1912, but KM, though mildly indifferent to political freedom, finding the world ‘too full of laughter’ to spend time with ‘strange-looking’, ‘deadly earnest’ suffragettes, was an energetic exponent of sexual freedom, far more experienced than Murry.

In her three London years, this newest of ‘New Women’ had had affairs with both men and women, undergone a late miscarriage, and possibly an abortion, and married – the marriage was unconsummated; she and her ‘husband’ co-habited for less than twenty-four hours. She had also, at some stage almost certainly been infected with gonorrhoea. She would tell Murry about the marriage, but little else. Murry tells us that ‘she destroyed all record [she refers in the Journal to her ‘complaining diaries’] of the time between her return from New Zealand to England in 1909, and 1914.’

If she confided the untold secrets of her early life to the ‘complaining diaries’, we cannot know but it is at least probable. While still in New Zealand, together with the works of Balzac, Tolstoy, Zola, Flaubert, Maupassant and other European masters, we know that she read the then popular diaries of Marie Bashkirtseff. Bashkirtseff, a friend of Maupassant, was a wealthy Ukrainian painter (a career as a singer had been cut short by health problems), who spent much of her short life in Paris and died there of TB in 1884 at the age of 25. Even in their bowdlerized form, her confessional diaries reveal a fiercely ambitious feminist with little patience for bourgeois hypocrisy, a seductive model for K.M.’s own journal, and life.

Bashkirtseff however explicitly intended her journal for publication, which K.M. did not. Indeed on the flyleaf of her 1915 diary is a short note, ‘I shall be obliged if the contents of this notebook are regarded as my private property’. She was twenty-six but it has a curiously adolescent ring.

Throughout her life K.M. routinely destroyed papers. Leaving Switzerland for Paris in 1922 she writes, ‘Tore up and ruthlessly destroyed much. This is always a great satisfaction. Whenever I prepare for a journey I prepare as though for death.’ Given the astonishing number of journeys for which she prepared in her short life, it is remarkable how much material she left behind (and must have carried around with her). In her will, written in August 1922, she instructs that all her manuscripts, notebooks, papers and letters be left to John M. Murry, adding, ‘I should like him to publish as little as possible and to tear up and burn as much as possible.’ Murry’s detractors later criticised him for publishing as much and burning as little as possible: ‘editorial scavenging’, wrote one, ‘boiling Katherine’s bones to make soup’ wrote another.

In his introduction to the Journal he is less than open about his editorial ‘policy’ in making his selection from the papers which he inherited – over forty notebooks and diaries and hundreds of loose sheets of paper. The quality he claims to be seeking to convey, he writes, is ‘a kind of purity’. In so doing, his critics argued, he created an idealised picture, an over-rarified spirit, toning down material which might reflect in his view badly on her. Some complained that he left out reference to her ‘less conventional sexual proclivities, others like K.M.’ s great friend Solomon Koteliansky regretted that he ‘left out all the jokes’. Leonard Woolf missed her ironic humour and fundamental cynicism.

The impression we get of Murry is of a rather dour, humourless character, handsome and attractive to women, but immature and unable to face too much reality. And K.M. may well have represented too much reality: volatile, and moody, a habitual liar who valued truth above all things, self-centered and acerbic, and ill (he found this very difficult), but such a life-force that no amount of ‘purification’ can diminish the thrill of the Journal. ‘Touched-up’ it may have been, but this is a multi-faceted, and utterly credible self-portrait of a writer struggling with her craft, an invalid doing battle with her failing body, a voracious reader, a keen eyed observer of others, and of herself, an early twentieth-century woman at odds with convention, fiercely individual, racing against time.

Unloved by her mother, in her teens K.M. lost her adored grandmother, the one person on whom she could rely to comfort her, with hot bread and milk, and ‘a little pink singlet softer than cat’s fur’ around her feet. Her beloved brother was killed in the War, within weeks of arriving at the Front. The men Katherine loved proved unreliable, the women too. Friends were rarely a source of comfort for long. K.M. was demanding and fickle. It is almost as hard to keep track of the people in her life as it is of her addresses, so rapidly did they go in and out of favour, their initials appearing for a few pages of the Journal then disappearing. Apart from Murry only her life-long friend Ida Baker, (aka Lesley Moore) features to the very end, but try as she might to provide comfort and succour, and L.M. tried to excess, she could never replace Grandmother Dwyer, her ‘best’ efforts provoking angry irritation, followed by guilt. At various times flat-mate, housekeeper, travelling companion, nursemaid, generous provider of loans, furniture, clothes, K.M. needed L.M., but found ‘something profound and terrible in this eternal desire to establish contact’, quite cruelly evoking her puppy-like devotion, ‘If I do absolutely nothing then she discovers my fatigue under my eyes’.

‘I’d always rather be with people who loved me too little rather than with people who loved me too much.’ Did Murry love her ‘too little’? He most certainly loved her a great deal less in sickness than in health, and candidly included K.M.’s references to this: given than he would behave in a similar way to his second wife, it is possible that he saw nothing blameworthy in distancing himself from the coughing and the pain. It would seem that K.M. got from J. the love that she required: ‘why I choose one man for this rather than many is for safety. We bind ourselves within a ring [how easy it is to miss her subtle use of ‘within’ rather than ‘with’] and that ring is as it were a wall against the outside world’. The Journal offers touching glimpses of their life together, ‘After tea we knitted and talked then read’, ‘Played cribbage with J. I delight in seeing him win’ – not exactly the hurly-burly of the chaise-longue. Towards the end of her life, bravely accepting that ‘life together, with me ill, is simply torture with happy moments’ and acknowledging that they shared ‘almost nothing’, that the two of them ‘are only a kind of dream of what might be’, she still longs for him. ‘I do not feel that I need another to fulfil my being, and yet having him, I possess something that without him I would lack … to be together is apart from all else an act of faith in ourselves’ . To be herself for Katherine was to be a writer, and Murry enabled that, from the next room, the next street, even from the far side of the Channel.

The Journal is not a narrative record, no use indeed as an historic document. Apart from her mourning dreams of her brother, and a brief note by Murry that ‘no single one of Katherine Mansfield’s friends who went to the war returned alive from it’, there is no mention of the defining events of 1914-1918. The occasional tantalising social detail leaves one longing for more: on 14th April 1914 she writes, ‘Won a moral victory this morning to my great relief. Went out to spend 2s 11d and left it unspent’. What was she going to buy? Though there are occasional passages of self-criticism, the Journal is not a confessional diary, and there are moments when we feel that we know more about her neighbours than we do about her. In her final ‘entry’, for want of a more accurate word, Katherine includes a short wish-list: a garden, a small house, grass, animals, books, music, pictures. It hardly differs from a list drawn up some years earlier and is dreadfully sad. Her material wants were so modest and she had gathered barely half of them.

More than anything throughout her life she wanted to work, to write, and much of the Journal is a writer’s diary, vividly describing the daily struggles, successes (rare) and failures (frequent) of the writer. ‘It’s the continual effort – the slow building up of my idea and then, before my eyes and out of my power, its slow dissolving’; ‘… what is it that I do want to write?; ‘I look at the stories that wait and wait just at the threshold. Why don’t I let them in?’. Time and again the cry goes up, ‘It’s not good enough’; ‘I didn’t get the deepest truth out of the idea’; ‘Musically speaking it is not – has not been – in the middle of the note.’ Constantly critical of herself as a writer, she does not spare other writers, even the ‘greats’. Worried about her own writing, she is reassured to read Gorky and ‘realise how streets ahead’ of him she is; Turgenev is ‘such a poser’; Forster ‘never gets any further than warming the teapot.’ Chekhov she admires unreservedly and Dostoevsky too, for his ability to build up a character from ‘vague side-lights and shadowy impressions’, so that when he at last turns a full light upon him, ‘he behaves just as we would expect him to do.’ She could be describing her own writing.

Vignettes, memories, sketched passages for future stories, simple observations of street activity or chance encounters all delight with her mastery of detail: the ‘endless family of half castes, who appeared to have planted their garden with empty jam tins and old saucepans and black iron kettle without lids’; a dog ‘so thin that his body is like cage on four wooden pegs’; a little French boy ‘bursting out of an English tweed suit that was intended for a Norfolk, but denied its country at the second seam’, a baby ‘at that age when it droops over a shoulder … when it cries, it cries as though it were being squeezed’. Ill as she was towards the end of the Journal , more often than not confined to one room, looking at her reducing world through a window, she didn’t lose her eagerness for people, for characters, for nature, and for words. Her eye remained as keen, and her ear as acute. She never lost her fascination with life, even as her own ebbed away.

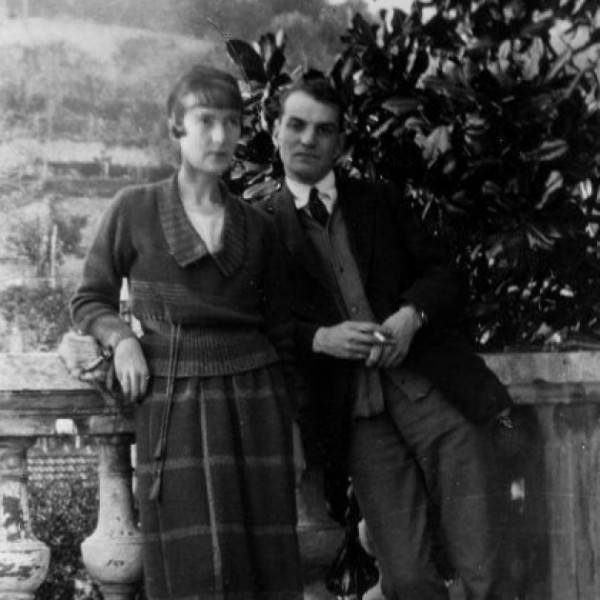

This photograph appears in her last passport.

In his Introduction Murry writes that Katherine died ‘suddenly and unexpectedly on the night of January 9, 1923’, unexpectedly maybe for him, who for years had denied the symptoms of her illness, deliberately blinkered himself to a progressive decline that is obvious even from her photographs. But Katherine did not shirk the reality. Her most ‘confessional’, and tragic entries describe the illness which is swallowing her, the pain, the breathlessness, the cruelly limiting fatigue, the despair and the hope.

Ironically while he was so scrupulously honing the dead Katherine’s image, Murry was shaping his second wife Violet Le Maistre into a second K.M., a pale reincarnation: an aspiring writer, similar in looks to the young Mansfield, she quickly adopted the same severe hair cut, and almost identical hand-writing, bore a daughter whom Murry named Katherine, and sickened and died of TB before she was thirty. Somehow, and although Murry has been, probably fairly, charged with falsification, manoeuvring, idealising and sentimentalising, a flesh and blood, living and dying Katherine Mansfield escapes the editorial knife, and emerges from the pages of the Journal.