After three year as ‘a desert island housewife, unaware of war or peace, and without suet or bottled fruit’, Nona Ranskill returns to an England that she doesn’t understand and which doesn’t understand her. Having left a country still enjoying a fragile peace, she returns to one where war has become a way of life, bringing with it a set of rules, conventions and priorities which have become so entrenched that only an outsider would dare to question them.

‘Was there any truth in this strange island where laddered stockings, a lack of notice boards and an illiterate song had more power to rouse emotion than death and destruction and the smashing of bombs,’ asks Miss Ranskill, and we can hear the author’s voice, as clearly as we sense her shock when Nona’s old school-friend asks of her airman son, ‘Have you had any good prangs lately?’ War has stiffened upper lips to the point where death must take its place along with other inconveniences, evacuees, billeted soldiers, the non-keeping qualities of flour and rough hands.

Nona’s desert island has been shared with the Carpenter, the capital letter indicative of the fact that this is no ordinary carpenter, and that any similarity to the best known of all carpenters is purely intentional. Both Miss Ranskill, as he addresses her, and Reid, as she addresses him, in accordance with the old social niceties, have been washed ashore following somewhat implausible accidents, he some years before her, as a result of ‘something to do with a winch’, she in an attempt to retrieve a dropped hat. The allegorical nature of the opening chapters is barely disguised: we are dropped straight into a sort of pre-lapsarian paradise, in which social rank counts for nothing and a man and a woman can live chastely side by side, where fresh water flows sufficient to slake their thirst and there are wild plants and fish aplenty to eat. Wood and shells can be whittled into shape as bowls and saucers, beds and a boat, bones shaped into needles and Nona’s long hair twisted into thread. Redundant ten-shilling notes find better use as kindling for the fire and a few stones create a hearth to ‘make it more homely’, one of the Carpenter’s favourite phrases.

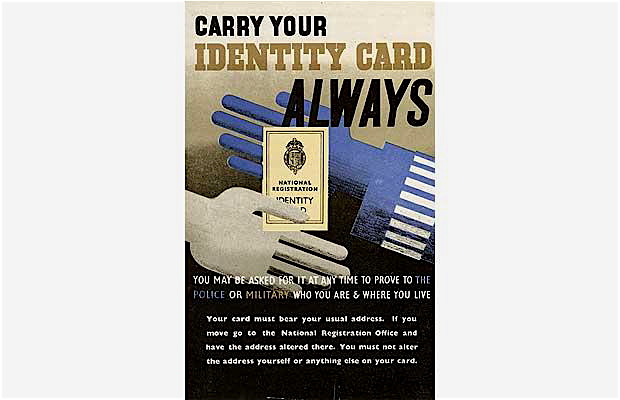

For Nona and for the Carpenter, home, conjured up in their touchingly evoked game of ‘going to the pictures’, is, for one, bread and milk by the nursery fire, with her sister Edith in their red dressing-gowns, and for the other ‘a cat on the rug, a plant-pot in the window and a bunch of flowers on the side-table’. But there is a cruel irony in the title. Having buried the Carpenter (not a spoiler – this is in the opening paragraph) Miss Ranskill does come home, as the title says, but it is not home as she had pictured it during all those years. ‘All the comforting small pictures she had made for herself of bedroom armchairs, tea by the fireside, the welcome of friends and the safe luxury of houses had left her mind. There was nothing left of them.’ And this is before she has been faced by baffling demands for coupons, or the sheer impossibility of buying stockings, or bananas, or hair-grips; and before she discovers the need for an identity card or hears talk of Objectors, and conchies, and Quislings and Nasties and the ATS, and the WAAF and ARP. ‘Even the language was secret from her, full of strange words and alphabetical sequences.’

‘Was she perhaps a trifle mad?’ If Miss Ranskill doesn’t understand the country in which she has landed, they most certainly don’t know what to make of her, a scarecrow (this is the author of Worzel Gummidge) of a woman, with straggly hair, threadbare, shrunken clothes and no shoes, who thinks it is possible to pick clothes from the dress shop racks and pay for them in the old way: no wonder that before she has even gone, empty handed, through the door, the rumour is already rife that she is a German spy, and the police are on her trail. In other hands this might be the stuff of nightmares, but Barbara Euphan Todd treats it with such a light touch that very quickly it is not Nona we worry for, but everyone else, seen through her ‘innocent’ eyes, behaving in ways that defy common sense and to an outside observer border on madness. The description of her bossy old-school-friend, Marjorie, leading her team in ‘extinguishing an incendiary bomb’ in the greenhouse, with a stirrup-pump is gloriously funny. Why should Nona think it is anything but serious, until Marjorie is once more recognisable as the school prefect she remembers, not over fondly, ‘Jebb, your tunic isn’t buttoned properly, Sprink, your shoe lace is untied. You might have tripped and upset the bucket …’.

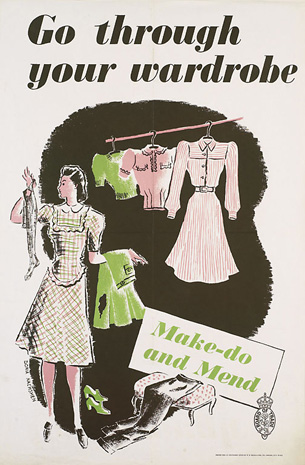

For Marjorie, as for many others, whose development like hers has been ‘arrested midway through the last term in the sixth form’, the war, for all the loss and discomfort it brings, has provided a setting in which one time Head Girls can take up their old places, put on their uniforms and lead their teams out onto a fresh playing field. Up against a very different team from the girls from the Towers, they can bring the Nasties down to size by ensuring adequate supplies, no longer of pens and India rubbers, but of soup, tinned fish and candles. They can make their little bit of England a safer place by turning their rose beds over to lettuces and parsley. ‘Dig for Victory’,‘Jump to It’, ‘Be a Sport and Save the Soap’, ‘Make Do and Mend’, echoing the language of school assemblies, the new rules, lest anyone forget, them can be hung on walls, painted on oil cloth, poker worked into panels.

With their girls behind them, Marjorie Mallinson and Miss Philips, Nona’s compliant sister’s reluctant landlady, and thousands like them will carry on bottling fruit in place of the unobtainable tinned fruit, which none of them ate when it was obtainable; they will carry on making rose-hip syrup for the children, when they have long ago and with sighs of relief seen off their unwelcome evacuees; determined to keep up standards that were shallow in the first place, they will make clothes out of old bedspreads when they have more clothes than they need in their wardrobes. When Miss Ranskill arrives and asks why – Why not spread the butter ration thickly one day and enjoy it, rather than suffer bread and scrape for seven? Why not have ten inches of hot water in the bath rather than six, when the unused water will go cold? Why wear shoes when one is more comfortable without? ‘… like a kindergarten child who had been jumped into the sixth form of a high school’, Miss Ranskill asks the questions a child might ask, unintentionally, but effectively challenging rules and priorities.

Her island years, with the thoroughly good and honest Carpenter, have washed her clean of the old prejudices and assumptions. Her easiest and most comfortable encounters are with children and with the young. She understands the significance of a lost penknife, and is happy to be instructed by a small boy as to the varying tones of the air raid siren and on how to use a gas mask. She knows how to reassure a child, understands that a warm hug is more effective than exhortations to brace up. And she appreciates why a young airman might want to defy the social expectations of his parents and choose to marry a girl because she was ‘comforting’.

Barbara Euphan Todd’s is too subtle and too easily amused for her irritation to evolve into full blown anger, but it comes close in her damning descriptions of the do-gooders who do no good, and haven’t an ounce of ordinary everyday humanity in them, cutting them down to size with a throwaway phrase. To reverse the old dictum it would be tragic if it weren’t so funny. Touchingly sad and ordinary encounters are balanced by sparklingy funny set pieces, as well as perceptive and troubling visions of a post war future, when the old values are going to need to be dusted down and revived. A generation of fatherless boys who have grown up in the war years will have to learn how to live correctly; young servicemen – and Todd has seen this after the First World War – will have to forget that they were once heroes and cut a new path.

The message of Miss Ranskill Comes Home is one of quiet and unassuming goodness, embodied first in the Carpenter, whose spirit lives on in Miss Ranskill, and who continues to deliver strength and courage to her in their posthumous conversations. His ghost does not rest until she no longer needs him. Barbara Euphan Todd’s husband, Lieutenant Commander John Bower, died in 1940. During the first dark years of her widowhood, the petty rules and increasingly obsessive concern with material things on the part of those around her must have appeared painfully absurd, when weighed against her grief. The naval commander was the younger son of a baronet, the Carpenter just a carpenter. Is it fanciful to conjecture that the two have been melded?