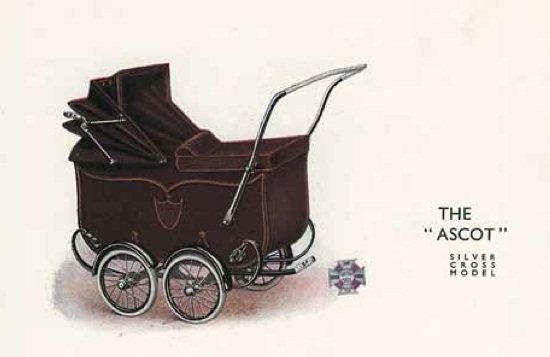

Although easily identified as Walpole Street, off the King’s Road in London’s Chelsea, where the author, Denis Mackail, and his wife Diana Granet began their own married life, Greenery Street is not so much a street as a state of mind, a place where love’s young dream can be lived out. In Greenery Street, ‘Everything is new, everything is exciting, and every excitement is doubled by the fact that it is shared.’ In Greenery Street, the ancient phrase, ‘So they were married,’ it runs, ‘and lived happily ever afterwards’ is modified: ‘For ‘and,’ say the inhabitants, please read ‘and therefore.’ Only a cynic would think of adding, ‘for a while.’ Greenery Street is where newly-weds make their first homes, privileged, upper-middle class newly-weds that is, where the husbands have private incomes to support a still niggardly salary, and the wives a comfortable settlement from their fathers. Something under £1000 a year does not make the young Fosters rich, but it allows them to live, like their neighbours, with two servants, in a five storey house, a ‘narrow little house’, as Denis Mackail describes it, for which the going rent in 2013 is £3,900 a week. Like their neighbours, they will find the house too small once the first pram appears in the hallway.

The house will squeeze them out to make room for another couple with the fairy dust of the honeymoon still in their eyes, two more young people, inexperienced in life and in love, still green. but bursting with optimism. That is what makes Greenery Street such a delight to read. The doors of Greenery Street open on to lives on which, we feel, the sun mostly shines. The ever watchful household gods – this is no ordinary street – are generally benevolent, and when they are not, are swiftly outwitted by a loving marital embrace.

A sequel was published in 1932, in which we meet Felicity and Ian six years on, with two children and a larger house. Praising it for its depiction of ‘real life’, Adrian Dover, the devoted keeper of the Denis Mackail website concedes that the events described ‘are less obviously dramatic than those related earlier’. Less dramatic! In Greenery Street Ian and Felicity meet setbacks, nothing more, and each one either dematerialises, is forgotten, or averted. One dream house is withdrawn from the market, but another, better house takes its place. Objections to the marriage of the two young things dissolve. A builder’s bill is covered by the sale of grandmama’s pearls, at a bad price but redeemed by a grateful sister and returned. The promised salary rise is confirmed. Chance, and a little, mild, cunning, restore a momentarily wayward sister to respectability, and, we eagerly delude ourselves, because that is the frame of mind we are in, to happiness.

It comes as no surprise that Mackail should have known P.G. Wodehouse. Not only do the Fosters, like Bertie Wooster, inhabit a world without malevolence, they are brought to life – Felicity’s wayward sister and loving parents, though swiftly drawn, rather more convincingly than the young Fosters – by a writer with a turn of phrase frequently equal to that of his better known friend. A young father, moving on from Greenery Street, clutches the keys in one hand while ‘in the other he grasps a wicker basket wherein the family cat is wretchedly revolving on its own axis’; ‘his heart melted to the consistency of a lightly-boiled egg’; ‘… with the handicap of six years at public school and three years at a university, he was lucky enough – and knew it – to be earning anything at all’, and, brilliantly, of Ian’s vituperative letter of dismissal to their housemaid, ‘it was a letter which, treated in the right way, might have earned the recipient a safe income for life.’ A promising early career in stage design had been cut short by the War, but Mackail retained from it an ear for dialogue: the short set pieces that he inserts are so reminiscent of another contemporary, Noël Coward, that the ring of the clipped vowels is almost audible.

Mackail’s characters don’t go in for much serious conversation. Sad thoughts are brushed aside. Any marital altercations are quickly resolved in tears and kisses, and there is little heart searching or lengthy introspection. Conventions agreed and adhered to make for a comfortable life. Just for a moment, having contrived to bring to an end his sister-in-law’s affair, Ian questions his motives: ‘What had he really been after? Daphne’s happiness, or just – just the common, conventional fear of scandal?’ Poor Daphne, swept up by the Bright Young Things, a kind woman, with a kind husband, and a sad little crib in the attic, which she bravely offers to Felicity but will not discuss.

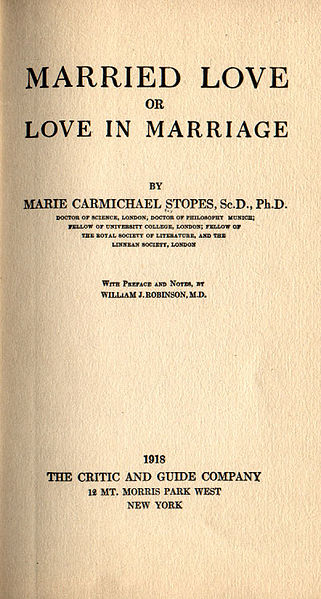

Tucked behind Felicity’s limited collection of books, out of sight, but not of reach, of Felicity, or her husband, her maid or her cook, is a copy of Married Life, a thin disguise, one assumes, for Marie Stopes’ Married Love, published in 1918, in good time for the young Fosters, but just too late, for sister Daphne, married ten years before the opening of Greenery Street.

Denis Mackail shows us a tiny corner of a society in transition: marriage is still in the gift of parents, but chaperones are no more than a formal presence at dances, and sexual freedom is beginning, if only for the very few. The shadow of the Great War has passed and few question the belief that it was the war to end all wars. There is just one reference to a vaguely sinister beggar who may or may not be an injured veteran. Impossible to believe that Greenery Street was published less than seven years after the end of the war, and in the same year as Mrs Dalloway. Or, in this starry-eyed hymn to marriage, that the annual number of number of divorces had more than quadrupled since before the War. Divorce, like death, has no place in Greenery Street. I am not sure in what corner of London the Mr and Mrs Younghusbands of today live, but I clearly remember as a young, unmarried, woman walking home in the early evening, past the newly ‘knocked-through’ basement kitchens of Islington (the 1970s equivalent of 1920s Chelsea), and seeing the pretty young mothers serving high tea to toddlers in dungarees, a silent picture of domestic bliss, or so it seemed.

The Fosters, the Lamberts, the Binghams, and all the other young marrieds, are, so long as they remain in Greenery Street, only removed by a few degrees from the fairy tale characters in Felicity’s limited bookshelf and, like Persephone’s other glorious fairy tale, Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, Greenery Street is a delightful, untroubling, buoyant read. Dotted with fascinating domestic detail, it’s a sort of Carlyle’s at Home ‘lite’: unpunctual, drunken servants with unsuitable men friends, neighbours borrowing and not returning spoons (and a step ladder and a fish kettle), dealings with builders and local tradesmen – not as fraught, nor as carefully accounted for as Jane Carlyle’s -, as well as trips to Andrew Brown’s (Peter Jones) for dresses, socks and library books (I know about Harrods library, but Peter Jones?).

We learn that two live-in servants suffice to run a five storey house, that it is normal for a newly married woman to return home for lunch every day of the week, and that on the parlour maid’s day off, it was usual for the young couple to eat out. And we realise that we might have had more in common with Jane Carlyle than with Felicity Foster and her neighbours.

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Cheerful Weather for the Wedding by Julia Strachey (Persephone Book No 38)

The New House by Lettice Cooper (Persephone Book No 47)

Patience by John Coates (Persephone Book No 99)