Half way through They Knew Mr Knight Dorothy Whipple offers a description of what constitutes , to borrow Winnicot’s term, a ‘good enough’ family. ‘The growing children were dependent on their parents; their parents were bound to each other by affection and interests which were perhaps made mutual by lack of money. Thomas could not afford a car, a club or golf; he therefore spent his spare time with his family. It is 1928 and for almost a decade, ‘the Blakes had been, like a happy country without history. They had lived in the Grove, holding together’.

The easy mutuality of the couple’s life finds outward expression in their garden: ‘… Thomas liked to cut down, root out, dig and mend fences, while Celia liked to plan, plan, tend, tie up and tidy.’ A family excursion into the countryside was bliss, then Celia ‘walked in contentment. They were all together, all well all happy’. But there is a shadow over this little Garden of Eden in the Midlands, which will break up the family.

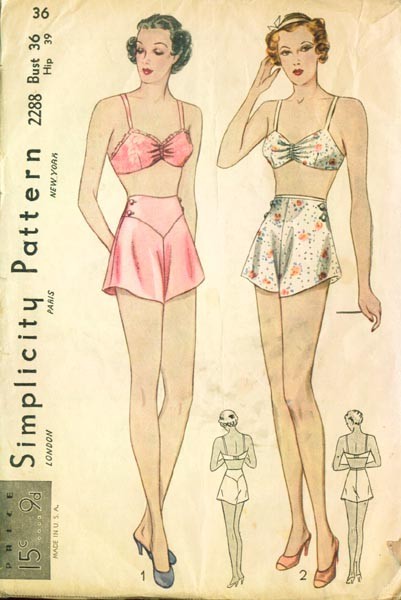

The fine fault lines are evident from the start. Thomas takes a warm pride in providing for his wife, Celia, and children, Freda, Douglas and Ruth, but providing for his extended family, his mother, sisters and feckless brother Edward is burdensome, and stretches his patience and finances to the limit. He dreams of retaking control of the family engineering business, lost by his father through incompetence, possibly compounded by a weakness for drink, but the harsh reality is that even his subordinate position there is not secure. Meanwhile, good as she is at ‘dusting, carrying shopping baskets, keeping accounts, sewing, soothing, smoothing for her family’, Celia nurses another self, not walled in by the preoccupations of house, husband and children, the self that, in another life, might have waved a Suffragette banner or written a novel, the self that might have made a home fit for the elegant furniture from her childhood. She admits to herself that loving Thomas and the children is ‘almost enough’, almost, but not quite. Seventeen year old Freda yearns to float free of her modest middle class family. There is little focus to her ambition other than to have her hair permanently waved and live out her fantasy of a life of luxury and glamour, and to avoid, at all costs, becoming a teacher.

Douglas, a budding scientist, and Ruth, the nascent novelist, observant and amused by life, are well-grounded survivors, whose plans for the future are in tune with their talents. It is the dreamers, Thomas and Celia, who are the most vulnerable, the most susceptible to the dangerous charm of Mr Knight, the larger than life financier, whose chance entry into the life of the Blake family will first raise them up beyond their wildest fantasies, then dash them down, and come close to destroying them.

In her Afterword, Terence Handley MacMath likens Mr Knight to Satan; in the current Persephone Biannually (Autumn-Winter 2011-2012), Adèle Geras states unequivocally that ‘Mr Knight is in fact the Devil’. Someone once described to me how it felt to be in a room with a well-known fraudster, who must remain nameless. ‘It was’, he said ‘like being in the presence of pure evil’. And, against the fiery background of the iron furnace, Laurence Knight appears to Thomas, in his dream, as the devil. But the dream fades, fear gives way to amusement and Thomas begins to look for a way to capitalise on his fortuitous encounter. With his millions, Knight is not the devil, but the answer to prayer. The Blake fortunes are about to be changed. Like countless others Thomas falls for the Devil’s charm.

Murdle, Melmotte, Hatry, Madoff,and more, literature and life provide no shortage of examples of seductive swindlers, and Knight can charm. Even Celia is not immune to this at first, admitting as she dances with him, that his face though ‘coarse and strong was not without attraction’. Only later when she has watched him stand by, amused, as her son Douglas has his heart broken, does she see him in his true colours, ‘he’s a gross, sensual grabber. I think he’s revolting.’

Thomas dismisses Celia’s opinion. ‘Celia judged Knight by womanish standards, a man judged a man differently’. Knight makes Thomas feel special. He gives him back his self esteem. Above all, he takes him back into the world of men, a world of cigars, and clubs, and golf, and money. Family outings and weekend gardening together become things of the past. The schism is marked, when the Blakes make their first significant move up the housing ladder, to the ironically named ‘Fairholme’, by the acquisition of fashionable twin beds condemned incidentally by Marie Stopes as the invention of the devil’.

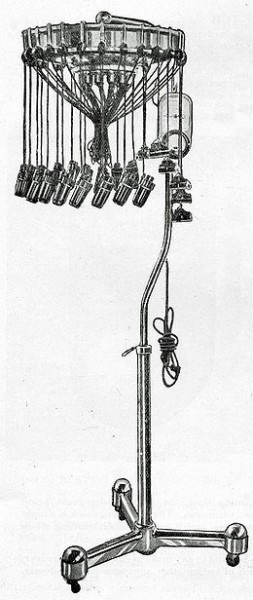

Celia must make her life among the women. As Thomas is able to provide more and more for his family so Celia’s role is reduced. One by one the domestic tasks that gave meaning to her life are taken over by a growing body of servants, and the family scatters: thanks to Mr Knight Douglas can go away to boarding school, and Ruth to a pensionnat, while Freda provides company for Mrs Knight, lonely, bored, and, thanks to the little trays that punctuate her days and provide her principal comfort, overweight. When her modest kitchen was her own, Celia could offer warmth and a hot drink to visiting tradesman, and food to the needy; but the kitchen at Fairholme is Cook’s domain, and she must pursue another form of charity, so ‘she sat on committees and undertook to sell tickets for innumerable affairs.’ As Thomas was emasculated by the loss of the family business, so the family’s newly acquired wealth diminishes Celia’s role. She falls ‘into the prosperous woman’s habit of “passing the time”‘. Only her garden keeps her in touch with her self.

If any woman is to be envied, it is Carrie, the barmaid. Making her own living she can shape her own life, and in the process make a man of Thomas’s brother Edward. She is capable and kind, and generously unforgiving of her snobbish in-laws. In all the change and collapse and ultimate, partial, regeneration of the family, if not its fortunes, Carrie is the one whose path, thanks to commitment, hard work and love, moves steadily upwards. As Knight is evil, so Carrie is good.

They Knew Mr Knight is a strongly moral, even Christian novel. When, at the end, Celia rejoices that her life, which has been so disturbed, is suddenly sorted out, and things ‘put into their right proportion’, it is God she thanks.

The religious message is perhaps, like the clear social and sexual demarcations, of its period, but the moral tale of the consequences of need, greed and the chance encounter is the stuff of folk tales, told by Dorothy Whipple with a light touch and sharp humour, aphoristic wit, and an eye at times almost cinematographic.

While charting its break-up, Dorothy Whipple paints a rivetingly complete picture of a1930s household: the houses, the servants (even a modest semi had a live-in maid), the gardens, the food, the clothes, down to the undergarments that Freda sews for herself from the best crèpe-de-chine, a lost world where a second subscription at Boots’ lending library is a privilege of the rich.

Quotes ….. do share your favourites

‘She missed the simple, busy life she had lived in the Grove. She missed her kitchen and her cooking, and she was cut off from the back door, which opened, it had always seemed to her, on another aspect of life altogether. She could no longer comfort the coal man with a hot drink on a cold day, or advise the window-cleaner about the placing of his children at work, or ask the vegetable woman in to get warm or rest a little.’

‘“Oh, these beautiful girls!’ she thought. ‘Why do they come into young men’s lives? They only go out again and the young men are spoiled for what’s left. The ordinary is what most of us have to put up with. Poor women, we can’t all be beautiful, any more than all men can be beautiful. Women put up with all sorts of men, but men run after beauty.”’

‘Poor mothers they are pretty helpless. They dose the stomach for the heart and try to staunch the wounds of love with decoctions of egg.’

‘Mrs Knight did not move easily; her corsets would not let her. The physical endurance of stout, restricted women is not sufficiently realised or admired.’

… gradually Mr Knight had undermined Thomas’s fundamental honesty by persuading him, casually, that the dishonesties

… and questions

Blogger ‘greenroadbook’ (see below) suggests that with more financial acumen Celia might have been able to warn Thomas against further entanglement in Knight’s schemes. But was it in her character to advise? At what point might she have intervened? Would he have listened?

Blogger ‘danitorres’ considers the characters to be well-defined. ‘greenroadbooks’ would disagree in the case of Mr Knight. My feeling is that such men, even in the flesh, do not seem quite real. Any thoughts?

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Someone at a Distance by Dorothy Whipple (Persephone Book No 3)

The Priory by Dorothy Whipple (Persephone Book No 40)

The New House by Lettice Cooper (Persephone Book No 47)

Princes in the Land by Joanna Cannan (Persephone Book No 63)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

Dorothy Whipple once again turns a shrewd eye on the foibles and shortcomings of her characters and once again they fall from grace, learn from their mistakes and find a sense of redemption by story’s end (well, some of them anyway–the ones you care most about).Her cast of characters are always well defined and developed no matter what mistakes they may make. With every new Whipple novel I read I seem to find a new favorite, so compulsively readable are her stories. They are never mere entertainments, though entertaining they are, but show a surprising depth and weight. danitorres

The characters are all brilliantly drawn. With the exception of Mr Knight, there is no obviously good or evil character, everyone has their moments. Even Freda, the eldest daughter, comes across as flawed rather than unpleasant. I felt terribly sorry for her when she rushes into a less-than-satisfactory marriage. Whipple makes it clear that one of the reasons of the tragedy is Celia’s detachment from the outside world. She knows nothing of finance or office, “a man’s world”. Hence she can neither warn Thomas, nor realise when he’s falling in over his head. Nor can she financially support the family when their new world comes crashing around them. This is a lesson on why female empowerment is so important. greenroadbooks

6 replies on “Persephone Book No.19: They Knew Mr Knight by Dorothy Whipple”

Dorothy had undoubtedly read Dickens’ ‘Little Dorrit’ and Mr Knight is a 1930s version of Mr Merdle – a ruthless, unprepossessing, but very rich man who in the end commits suicide because he can’t face the legion of people whose lives he has wrecked. Mr Merdle, Mr Maxwell, Mr Murdoch – we still gape at them and run after them.

This is one of Dorothy Whipple’s three great novels. Celia, Ellen and Lucy are all essentially the same character – a middle-aged, middle-class housewife who is devoted to her family and thinks no evil. And Mr Knight most certainly has a very evil influence on the Blakes. They ‘know’ him in the biblical sense – that is, they get much too close to him and are more or less corrupted. Only Ruth, who has a firm identity of her own and no interest in his way of life, is not damaged.

Celia is the moral centre of the book and I was only annoyed with her twice – first when she over-reacts to Freda’s perm (like you might if your teenage daughter came home with a pin in her nose) and then near the end when she believes she sees God. Yet there is no denying that the novel is imbued with Christian values, and these are surely more durable than the values of Mr Knight. Celia’s God is simply the principle of right living; Dorothy’s code is more austere than we in the twenty-first century are used to. Freda has made the wrong marriage and didn’t want to get pregnant, but nevertheless ‘this child will be the making of her’. The Blake family have suffered an awful humiliation, but in the end avoid self-pity, because, after all, nobody has died and they are not starving. They will stay together and make a life. I wonder whether this is how Dorothy comforted herself when her novels went out of fashion?

I haven’t seen the 1945 film, unfortunately. Alfred Drayton, who was a very ugly man, played Mr Knight, and Mervyn Johns was perfectly cast as Thomas.

This is one of my favourite Persephone/Whipple books, because of the plethora of domestic detail, and the depiction of the lives that were lived, which are so different to the lives the current residents of those same houses would be living!

It is a very moral book. As an athiest, I remark more on the morality than a specific Christian message. At its heart, it is about greed, rise and fall and redemption. Redemption may well be an unfashionable message to hear nowadays, but I think it still relevant.

I would disagree with greenroadbooks about Celia’s role in the book. Today, yes, it would be folly of the highest order that a wife could, or would leave all that decision making to her husband with no input. But we must remember that this was an era before feminism, in which the emancipation of the female gender was gained. The suffragetttes, while important did not have the liberation of the female gender at the heart of their movement. Married women could not purchase their own property or have their own bank account. The concept of rape within marriage or domestic violence did not exist. While an exceptional woman could have warned her husband, the point, I think of “They Knew Mr Knight” is that neither Celia or Thomas WERE exceptional. They were simply decent middle class people of average intelligence trying to live their lives and raise their children within the same moral code in which they themselves had been raised and which utterly precluded the life experience that would have alerted them to the nefariousness of Mr Knight. And it is this moral code that allows them to recover from the ordeal they go through, and permits the possibility of redemption.

Having read “The Priory” (my favorite Whipple), “They Knew Mr. Knight,” and “They Were Sisters,” it was interesting to observe how Dorothy Whipple endows her female characters with similar behaviors across these novels. In particular is the appearance of the female figure who sees the world only in terms of her own comforts and desires (Penelope, Freda, Vera). These women all proceed to marry men they do not love in order to escape a distasteful home life and maintain a particular status among their peers.

Merryn suggests that Celia overreacts to Freda’s perm. What I took away from that scene was the pain of a mother recognizing that her child has taken its first determined step against family connections. I cannot think of any scene of warm conversation between Freda and the other members of the family, until after Freda reveals she is pregnant. Freda is disconnected from the family unit, and would rather disobey her mother than miss the opportunity to climb the social ladder. To me, this scene was Celia’s forewarning of what Freda’s disregard for family connection would lead to, namely, her elopement to an unsuitable mate strictly for the sake of avoiding poverty and loss of position.

Regarding the character of Mr. Knight, I think it is impossible to give nuance to such a figure. These men are all perception, hiding their true selves behind a socially acceptable veneer until the moment their true nature is revealed. Dorothy Whipple has portrayed this character completely accurately.

For the first half of this book I thought it was a real plodder with nothing like the page-turning style of ‘Someone At A Distance’. Then, at about the mid-point, Douglas had his crisis over the Diana Wilson girl and everything changed. I really thought he was going to top himself and devastate Celia absolutely. Then the pace really picked up after that until it started to slow down and come to a grinding stop with Celia sitting numbly in her kitchen, aware of every tick of the clock, just before she had her ‘Damascene’ experience. And then I realised that it was all meant to be like that. It was clever old Dorothy Whipple adjusting the pace of her writing to reflect the changes in the lives of the Blake family, describing the arc of their rise and fall. And as she slowed the pace and brought them back to where they started, she had more time for poetry in her writing, as in the section describing Ruth wondering around Field Place when they know they will have to leave it, and the opening paragraph of Chapter 29 when Celia is back in The Grove.

I liked the unwitting way that Whipple marks out the society of which she writes – a society in which Sundays are noticeable because they are silent, where people always put on their hats before going out, tramps mark out kind households with signs on gateposts, servants are in evidence in even quite lowly establishments, goods are delivered by tradesmen on regular days, and not every house has a garage or parking space.

Best quote: ‘Truth is a slippery idea.’

Amy is right; parents have always panicked when their teenage children declare their independence, and one way to do this is by altering the way they look! I saw one woman nearly faint when her daughter came home with a Mohican hairstyle, and I’ve seen an eighteenth-century cartoon in which a respectable burgher reacts with horror to his son’s foppish appearance – ‘Welladay!’ he cries, ‘is this my son Tom?’ So it’s been going on a long time.

Dorothy had no children but I’m sure she worried about the crises of her nephews and nieces. You’ll remember how in ‘Someone at a Distance’ Hugh threatens to stay in the army rather than tolerate his father’s behaviour – this is averted, and how it’s up to Lucy to save her sisters’ children, as described in one of the most moving closing paragraphs I know.

. . . . and my mother (91 next week) can still recall her mother almost pulling her hair hair straight again when she went home after having her first permanent wave!