Reading A Woman’s Place two things struck me almost from the start. First was the thought that this should be required reading for anyone new to Persephone Books. Perhaps it should even be Persephone Book No: 0. A Woman’s Place provides the contextual, historical, social background to so many of the novels. With a light and, largely, uncomplaining touch, Ruth Adam describes the changing patterns of women lives between 1910 and 1975, patterns determined for the most part by the forces of history, to which Persephone heroines must bend, or, at their peril, resist.

The second thought was that we are witnessing now, in the second decade of the twenty first century, yet another set-back in the slow progress towards sexual equality in the work place. And could those who fought for women to be given the vote possibly have imagined how slow it would be? For in late 2011 women are once more among the early victims of an economic downturn. Rising unemployment, cuts to benefits and childcare services combine again as they did in the last century to drive women back into the home. No wonder then that this month (November 2011) the Fawcett Society is urging women to take to the streets in rubber gloves and full-skirted frocks to stage 1950s tea parties. Some will be wearing handcuffs with which to chain themselves to a kitchen sink. If Ruth Adam were to see us now she might smile wryly and comment ‘plus ça change’.

Until the First World War, a woman’s place, was in the home, not her own home, but that of her father, brother, husband, or (in the case of domestic servants, nurses or teachers) that of her employer. Women’s pay, and fewer than a quarter worked, did not stretch to rent. When they waved off their men in 1914, they expected them back by Christmas. But by the summer of 1915, with more and more men needed at the Front, it had become clear that women’s war effort was going to far exceed keeping the home fires burning.

They were urgently needed in factories and on farms, in offices, and on buses and trams, in hospitals, and, behind the lines, in France. Yet it would be another three years before any of them won the vote, thirteen for those who were under 30 and neither householders nor the wives of householders and then it would radically alter their lives. ‘A similar quick change of character’, writes Adam, ‘has been demanded of them every ten years or so of this century. Men are not required to be flexible in the same way.’

It is this buffeting to which women have been subjected that makes A Woman’s Place so moving, even painful to read. In 1914 women did what was asked of them. For four years they did the work of men. Some were even paid the same as men. Equality seemed to be a possibility. But their expectations would be dashed, the promise of equal pay never materialised and rapid demobilisation at the end of the war put hundreds of thousands of women out of work. The wartime jobs vanished, and the returning soldiers reclaimed most of the others, and, if they were married, they wanted their wives back at home. Many single working class women returned to their pre-war positions: in domestic service, reluctantly and in smaller numbers; on the land, where they found their status improved thanks to the war-time work of the Land Girls; in factories, where thanks to the efforts of the munitions workers, conditions were better. Some improvement. Two steps forward and one back: they had hoped for so much more.

Some middle-class and professional women managed to hang on to their jobs, albeit at a lower salary than their male counterparts: in commerce, administration, shorthand-typing, and most especially nursing and teaching. Not well paid, these women were, nevertheless able to live independently. A new way of living was emerging. The number of unmarried, never to be married, women, already worryingly high before the war, had soared. Willingly or not, many women began to see careers as being for life, no longer a stop-gap between school and marriage. Events and the new economics of work had consigned the ‘old maid’ to history, and a card game.

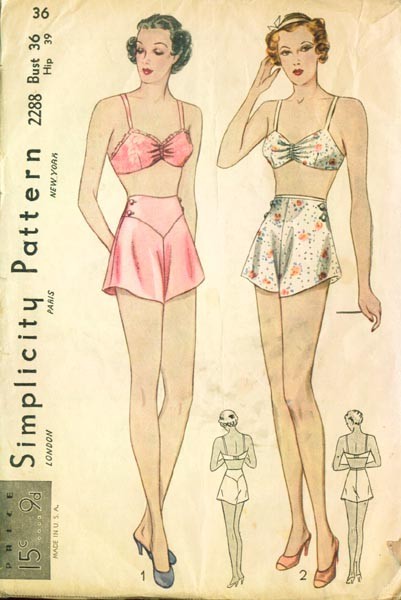

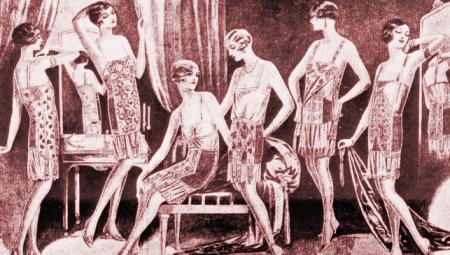

In many ways, though far from heralding full equality, and certainly not for women of all classes, the 1920s was something of a golden age. The Bright Young Things may have had the best of it, but all women benefited from the changing fashions: shorter skirts, shorter hair, simpler hats, or none. ‘The new clothes made being fashionable a joyful experience, in a way it never had been before and never was again.’

A woman’s place is mirrored in her wardrobe, suggests Ruth Adam. The fashions didn’t last and nor did the brief upturn in women’s fortunes. The legislation clock could not be turned back: women had the vote, they could no longer be excluded from the professions (which did not mean that they were to be included in large numbers), divorce was a little easier and a little fairer. But the clock could be stopped. The Depression brought with it renewed hostility against women in work. They were to be put back in their boxes until they were needed again. Another decade, another change of role, another set of clothes – longer skirts, fuller sleeves, platform shoes, and permed hair (think of Freda in They Knew Mr Knight). A woman must be alluring. The magazines which had trumpeted freedom from domestic drudgery began to glorify it. Unmarried women were to find work where they could; the upside of unequal pay was that employers too them on as cheaper labour in the place of men. The married woman’s place was in the home.

It would take another war to release them once more. Now the fashionable woman was wearing khaki (Vera in Saplings), or factory overalls. Like the First World War, the Second altered the lives of women in ways that could not be reversed. The Education Act, providing free schooling, and university grants for all brought an end to the cruel dilemma of parents agonising over the value of paying to educate a daughter who might give up a career for marriage. Had she chosen nursing, or teaching, or the civil service, she would until the late 1940s have in fact been compelled to do so. Thanks to Beveridge, Family Allowance would be paid directly to mothers, and their health and that of their children cared for under a National Health Service. Pre-natal homes, instituted to provide a safe environment away from bomb-threatened cities (Tell It to a Stranger) raised standards of maternal and infant care. Lessons learned as a result of the social mix enforced by the evacuation of the mothers and children (The Wartime Stories of Molly Panter Downes), for good or ill, would not be forgotten.

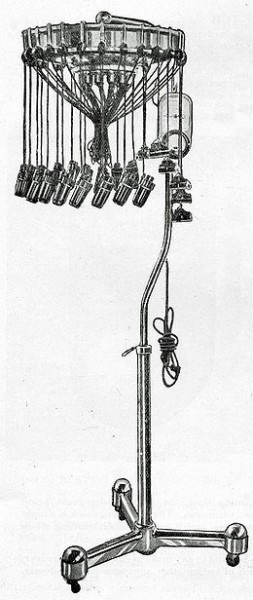

The aftermath of the Second World War like that of the First, brought with it a new period of underemployment for women – 2 million left their jobs – and a new look, the New Look. Tight-waisted, full skirted, calf-length dresses, were as far removed as could be from the austere utility clothes. Back in the home the woman was ‘all woman’ once more. In 1947 only 18% of women were in full employment. Live in staff were rare, live in British staff rarer still. No young working-class girl would choose domestic service – the wives in Penelope Mortimer’s Daddy’s Gone a’Hunting worry about their foreign cooks. For the first time middle-class and educated women were caring not only for their own houses, but for their own children. And that too was subject to fashion, dictated, until the 1970s largely by men, Truby-King, Bowlby, Spock.

By the time she died in 1977, Ruth Adam had witnessed some quite remarkable changes in women’s lives, the most radical either resulting from, or being hastened by, two world wars and a major economic crisis. She saw skirts go up again in the sexually liberated sixties, down again in the seventies when the ethnic look expressed the earth mother side of even the highest academic achievers. She saw the number of women in work rise rapidly to well over 50% and she saw their average pay climb slowly to a little over 55% of that of the average man.

A Woman’s Place is clear and richly informative and sharp it illuminates not only the past but our own lives. The last thirty years have not been as marked by the fits and starts that characterised the previous seventy. We have been spared the seismic changes of two world wars and a depression. Nearly 70% of mothers work, only slightly fewer than those with no dependents. But the disparity in average pay for men and women has not disappeared. There are fewer women in parliament than under the last government. Women were admitted to legal training in 1919. In 2011twelve judges sit in the Supreme Court: one is a woman. Where are we now? Where do we want to be? And what do the fashionistas say we should be wearing in 2011? Long skirts and teeteringly high heels …. Still we don’t have to follow them. That’s progress, of a sort.

Quotes ….. do share your favourites

My favourite has to be the one chosen for the flyleaf of A Woman’s Place, the closing paragraphs:

‘This demand for women to change their colour, like chameleons, to fit the background of their period was one of the penalties of the speed at which their emancipation had been accomplished. Major changes in their state had taken place within the span of each generation, so that every twentieth-century mother, in turn was amazed at the difference between her daughter’s life and her own.

‘A woman born at the turn of the century could have lived through two periods when it was her moral duty to devote herself, obsessively, to her children; three when it was her duty to society to neglect them; two when it was right to be seductively ‘feminine’ and three when it was a pressing social obligation to be the reverse; three separate periods in which she was a bad wife, mother and citizen for wanting to go out and earn her own living, and three others when she was an even worse wife, mother and citizen for not being eager to do so.’

… and questions

so many and yet they all come down to two:

What do women want?

Can they have it?

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Every other Persephone Book in the list.

What other bloggers have said about this book:

There are some absolutely fascinating tidbits in this book, stuff I never knew. Because the book was originally published in the 1970s, it tends to be a bit feminist at times, but I thought for the most part that this was a very smart book, not preachy or pedantic. Sometimes her tone is sarcastic and dry, but never bitter. I enjoyed what Ruth Adam had to say about superfluous women spinsters like me and widows who really didn’t have much of a place in early 20thcentury England. It’s interesting to see how things have changed, or not, in the hundred years since! agirlwalksintoabookstore