The remit of the book is very clear from the title: not ‘The Carlyles’, but ‘The Carlyles at Home’. Thea Holme is adamant that she does not intend to explore the Carlyles’ marital relations, the subject of speculation by biographers after their deaths, and if the biographers are to be believed, by their contemporaries too. Samuel Butler famously remarked that it was ‘very good of God to let Carlyle and Mrs Carlyle marry one another, and so make only two people miserable instead of four’; Ruskin noted that he ‘used to see the two constantly together – and there was never the slightest look of right affection.’ But Butler didn’t know them, and Ruskin was no expert when it came to marriage. And in any case there is no knowing. This is a picture of how and where a Victorian couple, a rather exceptional Victorian couple, lived, not how, or if, they loved.

It was at my mother’s suggestion that I first read The Carlyles at Home in the 1960s – sadly she didn’t live to enjoy Persephone Books: her library list (I clearly remember the 1950s visits to Boots Lending Library) would have been a close match with the Persephone catalogue. It was with her that I first visited Carlyle’s house in Cheyne Row. In those days Thomas Carlyle’s shower was still in place in the back kitchen. When I went back to 24 Cheyne Row two years ago, I found that the back kitchen had been turned into the National Trust office, and, so young were the personnel, no-one remembered having seen the wonderfully Heath-Robinson arrangement that TC devised for his daily ablutions – was he unusually fastidious for the period? Apart from the shower, I had recalled few details. Rereading Thea Holme’s book, I realised why: I was simply too young. What did I know (or care) as a teenager about builders, or budgeting, or moving house, or mending? The joy of reading The Carlyle’s at Home now, is that, grown-up, one can share so much with Jane Carlyle –share so much, when nearly two hundred years have passed, and yet be astonished by so much.

Arriving at their newly rented house in unfashionable, rural Chelsea (fresh milk could be obtained from the Rector’s house cow, five minutes walk away), they wait for the Pickford van (who else?) to arrive with the furniture. We, like the Carlyles, have picknicked on box tops in empty houses, while removal men worked around us, possibly even carpenters, fixing furniture. That is all comfortably familiar, but then Jane mentions bell hangers. Bell hangers? In a four storey house and one maid of all work, one can see the need for bells but were they not included in the furniture and fittings? Had the previous tenants removed them? Was it normal to provide one’s own? Jane’s letter to her mother is full of detail – laying and nailing down carpets herself, filling in gaps with pieces cut from old blankets, hanging cut down curtains from the house in Scotland, unpacking and sorting books -, but she sees no need to state the obvious, and her mother would have known what a bell-hanger did.

Between them the Carlyles wrote over 10 000 letters, now stored in a digital archive by the Duke University Press. For the minutiae of everyday life Thea Holme relies largely on Jane, but Thomas Carlyle, although touching more often on loftier subjects, was not above describing the despatch of oatmeal and potatoes in barrels from Scotland, regretting the failure to include the dried herrings that his wife had requested, but too late; nor did he fail to mention, frequently, the doses of senna taken to aid his digestion, nor the price of shoes – carpet shoes made of black shag cloth with three buttons, which would normally have cost 5s 6d but made to order cost 9s.

Both were much preoccupied with money, predictably since it was not until the publication of TC’s life of Frederick the Great in 1858, for the first two volumes of which he received the princely sum of £2,800 (roughly £200, 000 today), that they were to enjoy a reliably sizeable income. Prior to that in a good year he might have earned £800, in a bad year as little as £150. Their friend Geraldine Jewsbury noted that it was impossible to know whether the Carlyles were rich or poor. Jane may have asked herself the same question.

Unusually, perhaps for a Victorian wife, she took responsibility for most of the household finances, renegotiating the lease on the house (the rent remained at £35 a year for the duration), challenging builders’ bills, appealing in person to the Commissioners of Inland Revenue about a tax demand that TC would be pressed to meet (Income Tax had doubled in 1855 to 1s 4d – approx 6p – in the pound!). Her description of the Commissioners is masterly: ‘One held a pen ready over an open ledger, another was taking snuff, and had taken still worse in his time, to judge by his shaky, clayed appearance. The third who was plainly the cock of that dungheap, was sitting for Rhadamanthus [one of the judges of the dead in Greek mythology] – a Rhadamanthus without justice’, a passage that could have come straight out of Dickens. Jane’s pen was as sharp as her eye.

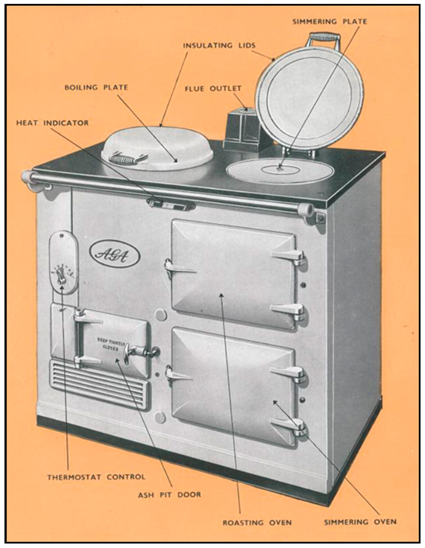

While Jane shielded him from such unpleasantnesses, TC continued to hold the purse strings, and she accounted to him for household expenditure, pleading, eloquently, in 1855 for an increase in her allowance. Her letter is not only elegant in style, and, it would seem, convincing, it presents a fascinating snapshot of their life: social historians trawl laundry lists, and bank books for this type of raw material. After twenty years in London, the couple are comfortably off. Their servant’s wage has doubled to £16 a year (they still have only one, not the same one – the saga of the maidservants’ coming and going takes up two chapters) and she expects a ‘meat dinner’, and, presumably, the same ‘beer money’ as her predecessors. Water has been laid on at a cost of £1. 16s a year plus ‘a shilling to the turncock’ – the turncock? – whereas previously they had paid only 4d a week to the water carrier. Gas light, installed in the kitchen and over the front door, is an improvement, but vastly more expensive than candles – one or two candles had been thought sufficient to light the dingy basement kitchen.

The food budget is interesting too, particularly for what it tells us about their diet, even more shocking to us in health conscious 2012 than it was to the 1965 reader: a pound and a half of butcher’s meat a day, for three people, two pounds and a half of butter a week, a pound and a half of potatoes a day. We know that TC didn’t like any other vegetables, and Jane mistrusted fruit on the grounds that it caused colic: when her doctor thought a daily intake of mutton chops and two glasses of good sherry a prescription for good health, who was to tell her that she might be wrong.

Her dress allowance, she suggests, by way of mitigation in the same letter, could be reduced from £25 to £15, ‘A silk dress, a splendid dressing gown, “a milliner’s bonnet” the less; what signifies that at my age? Nothing!’ But Jane did mind about her clothes. She was considered to be well dressed, but had very much her own style, refusing to wear either stays or the fashionable crinoline. In the early days she made do and mended, and turned pelisses, and made jackets out of scarves, with the same skill with which she darned the stair carpet, or cut up and remade an old mattress to sit upon a newly acquired sofa. But even then she drew the line at making clothes for her husband, her reason being that she was ‘an only child’: had she had brothers she would have been expected to sew shirts, and night shirts and drawers for them, as her sister in law, did and continued to do for Thomas. The past is another country.

But maybe not entirely. How easy, and enjoyable it is to share with Jane the irritation of noisy neighbours, although the noises are a little different: the early morning cock crow is rarely heard in Chelsea now; the tiresomeness of the hopeless family around the corner, in her case the Leigh Hunts, with too many children, living in squalor, and always on the scrounge: tea cups, spoons, porridge, tea and, less likely today, a brass fender, not all of which were returned; and the dog, little Nero, devoted companion and habitual escapee –we too know the agony of the lost dog and the mixture of relief and anger when they return; and we understand her irritation when, having made all the preparations for her first soirée, her mother produces a fresh supply of delicacies. And the builders, most especially the builders! How we sympathise: the boss who doesn’t reply to messages, the bricklayer who comes to measure up and never reappears, the tuneless singing (the Victorian equivalent of Radio 1?). Would Jane be surprised to learn that their descendants are still spreading dust, and putting their feet through ceilings, and saying a job will take six weeks when they know that six months is more likely? Perhaps a wry smile would cross her long, intelligent face.

In presenting the book by theme rather than chronologically, with a series of overlaid strokes, Thea Holme builds up a vivid and many layered portrait of Jane (and of Thomas Carlyle too, but he would not be sitting at the tea table with us), bringing us together with a woman who was both of her period and untypical of it, educated and clever, ambitious not for herself but for her husband. She was articulate and witty, loyal but impatient and short tempered; bursting with energy one day, bedridden the next, and the next – health was a constant pre-occupation. She met life’s problems with humour but came close to suicide. There would be much to talk about, and laugh about, but would we have liked her? Perhaps in small doses.