If you click on Books, on the Persephone Books website, and then under Categories click on WW2, you will find no fewer than eighteen titles. Most were written in part or wholly after the end of the war. A House in the Country was written and published during the war and has a particular immediacy.

The year in which the book is set, 1942, was perhaps the lowest point in the war, the darkest hour with no dawn in sight, and no one could be sure that things weren’t going to get darker still. Singapore had fallen to the Japanese in February. Rommel had captured Tobruk on 21st June. Allied forces were overrun and 25,000 British and Commonwealth troops taken prisoner by the Germans. Churchill considered it “one of the heaviest blows I can recall during the war”. The Dieppe raid in August had been a disaster. The brightest point, shortly before Tobruk was taken, had been the American victory over the Japanese at the Battle of Midway in the Pacific. Later accounts recognise this as a turning point, but the motley community of Brede Manor, the ˜house in the country”, would have had no reason to feel so confident.

In the first six months of 1942, 500 Allied ships had been sunk in the Atlantic. Charles Valery, owner of the beautiful Georgian house in the country, was serving on one of them. Jocelyn Playfair does not date her opening chapter, but working back from Tobruk we can be pretty sure that his lonely ordeal as the sole survivor from the Alice Corrie begins on about 7th June. A little over three weeks elapse between Valery’s escape from the blazing ship and his return to Brede, the beginning and the end of the novel.

Like the beam of the searchlights scanning the sky for enemy planes, one of several graphic scenes reminiscent of films of the 1940s, the focus shifts back and forth from the lifeboat where Charles, the man at war, a man of action, lies motionless and adrift in the Ocean, to the house (his, we soon discover), where Cressida Chance, the woman on the home front, is constantly on the move, tirelessly cooking and caring for a houseful of paying guests. For three years she ‘has never managed to find time to sit in the garden’. We are told very little about those three years. The PGs are transient. They have only the sketchiest of back stories, no more than we might, realistically discover in a brief meeting. Cressida’s story, and Charles’s, are revealed, retrospectively, slowly and partially. A House in the Country is a page-turner, because we want to know what has happened, as much as what will happen.

Charles is the voice of the fighting man, questioning, as he lies wounded, the value of life, the reasons why men fight, the nature of war itself, war which had evolved over centuries from a battle between one castle and another, one village and another, to something which for the first time involved the whole world, ‘now a man from a lonely ranch in Texas would go and fight in the jungle of Guadalcan, a boy from Western Australia would fly over a German city, and an Indian would march through Africa.’. As for the reasons for fighting, it seems to Charles to come down to the desire, above all, to conform: men fight because other men are fighting. But he has another reason of his own: he cannot bear the thought of German boots on the gracious curved staircase at Brede.

Man’s war, woman’s war, home front, battle front, three years have passed in which, whoever they are, war, has been the defining factor for everyone. For some it is an inconvenience: for the Greersons, reduced to three maids, for whom paying guests (men and women posted, away from their own homes, on war work) are ‘quite too much trouble’, for Cressida’s infuriating Aunt Jessie, and others like her who don’t see why they shouldn’t wangle petrol and hoard biscuits and run the central heating and have three lights in the drawing room and hot baths up to their necks, in fact go on as nearly as possible in the way they’ve been used to, for the ghastly Felicity Brent, put off joining up by the requirement to wear army underwear (no image for this unfortunately, but the description on the Imperial War Museum website says it all: underwear Lightweight khaki knickers (shorts) with an elasticated waistband ).There are those like Mrs Brandon, who sit on every possible committee, but on the night of the air-raid spends the night under her dining room table, and there are the meek who rise unexpectedly to the challenge. Jocelyn Playfair paints these characters with the same wry humour as Mollie Panter-Downes in her Wartime Stories (Persephone Book No. 8), and Virginia Graham in Consider the Years (Persephone Book No. 22).

Ordinary life for those who are able to see beyond their own selfish needs, who live without blinkers, acquires a new perspective, perhaps slightly surprising for a reader today. ‘It was frightening to consider how enormous personal worries and tragedies would look without the infinitely more immense background of the war to dwarf them into insignificance,’ reflects Cressida, while her brother, Rudolph, agonising over an unhappy love affair, declares, more prosaically, that ‘there’s always the war to fall back on’.

But the truth for the men at home was more complicated than that and Cressida realises it (for much of the book she is the voice of Jocelyn Playfair: there are passages which read as if they might have been the author’s own diary entries). It is she who compares the fear and exhaustion of actual battle with that other sort of hell, ‘living in England, surrounded by normal people, living near-normal lives, trying to do a job that seemed to have no end and no purpose, a life of exercises and long journeys in lorries from one English village to another … .’ Rudolph is, safely, stuck in England, but his sister recognises how much easier it is ‘for the lucky ones who happened to be actually fighting’.

Cressida Chance is perceptive and beautiful, and elegant and kind and unselfish and brave and, astonishingly, given all those qualities, hugely attractive as a character. She is, rightly, irritated by the petty selfishnesses of some of her ‘guests’. She rages against the men who ‘fought the last war and won it, and then threw away the vision of peace’, pitying our young fighting men who were babies in 1918, and sympathises too with the panic-stricken German boy on his first flight over England. She is the woman one would want to have been in the war. And Tori, the small, fragile, odd-looking, charismatic middle-European, is the man one would have wanted beside one: charming and strong and intuitive and with a very un-English understanding of women. We know that, like the other guests at Brede, he cannot be a permanent fixture. War moves people on.

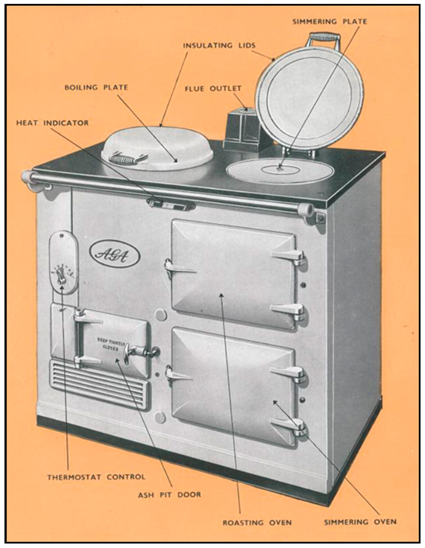

Cressida is quietly accepting of this, knowing that, like her dogs, she must live for the moment. She, and Brede Manor, are still points in a turbulent and uncertain world. ‘Her beauty, and that of the house had something in common, some effortless tranquillity which united them so that exterior details lost their disruptive power.’ In the kitchen, Cressida gazes at the Aga. ‘It seemed cleaner, squarer, more solid than usual, like a fortress for the simple, sane things of life; comfort, good food, warmth, friendliness ….’ . These are the things that women will always defend and perhaps that is a reason why WW2 books outnumber even “Family”and “Love” on the Persephone list.

quotes … do share your favourites

‘Oh, dear, Miss Ambleside thought, if only one could see a little ahead, how much simpler things would be. This aspiration, which she unwittingly shared with the General Staffs of all the belligerent countries, did not comfort her in the least. She, and the General Staffs, merely became more anxious and more irritable, because it was so annoying to feel that at any moment something might happen which would entirely ruin all one’s plans and render all one’s efforts a mere waste of time.’

‘…I think that to stay at home, to be unnoticed, to do every day the same things, to be bored, to be tired by work which no-one sees, to live in the same way that you have always lived, with only the difference that it is upon you that all the work will now fall, there is I think is the most severe test of all. There is no uniform, just old clothes becoming every day older, and no company such as a factory would give, no new interests, no sense of urgency, of being what you might call in the war.’

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Good Evening Mrs Craven: The Wartime Stories of Mollie Panter-Downes (Persephone Book No. 8)

Few Eggs and No Oranges by Vere Hodgson (Persephone Book No. 9)

Consider the Years by Virginia Graham (Persephone Book No. 22)

House Bound by Winifred Peck (Persephone Book No. 72)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

‘A House in the Country is not a cosy paean to countryside ways, but a deep, moving, and surprisingly controversial novel. Cressida Chance (wonderful name) lives in the house of the title, and has started taking paying guests. The idea of paying guests is completely foreign now, but it must have been an ingenious way for people to get a bit of extra money without demeaning themselves, and to provide houses for those who needed them during the war. If someone were to make a list of things which would attract me to a novel, having big old houses at their centre would definitely make the list. I have read few novels with so intriguing an angle on wartime living .’ stuck-in-a-book

‘This is not the most festive or cheerful book on the Persephone list, but it is beautifully written, poised on the edge of danger, with such interesting characters. If you have wondered what all the fuss is about Persephone books, this is a readable one to start with, if not the best known.’ northernreader