Published in the fifties by a writer already in her seventies, Lettice Delmer tackles illegitimacy, abortion and venereal disease, latent homosexuality, and, less fashionably, a stern Christianity. To do all of this, and in verse requires a most particular gift, and courage. Susan Miles had both, and the ability to tell a good story. Unexpectedly – no escaping the fact that blank verse may not be immediately attractive to every Persephone reader – Lettice Delmer is a page-turner, so sad that we might sometimes wish we hadn’t turned the page, but a true page-turner, and the verse form, again unexpectedly, contributes to this. The metre brilliantly adapted to evoke, for example, the rippling ease of an afternoon’s fishing, the unstoppable clatter of train wheels, and Lettice Delmer’s inner turmoil, it drives the story on, hitching the reader to its rhythm, so that we are no more able to put it down than Lettice Delmer is able to escape her destiny.

Like Alex Clare in Consequences (Persephone Book No. 13) Lettice is dogged by bad luck, and like Alex lacks the inner resources to fight back. Some thirty years after Alex she has been born into a different social milieu, but, in the early years of the twentieth century, the rising professional middle classes nursed aspirations for their daughters similar to those of the upper classes of the late nineteenth. While her older half-brother, Hulbert, will follow his father into medicine, Lettice will marry. What need for education, life-skills, or even common sense, when her path has already been mapped, a husband chosen?

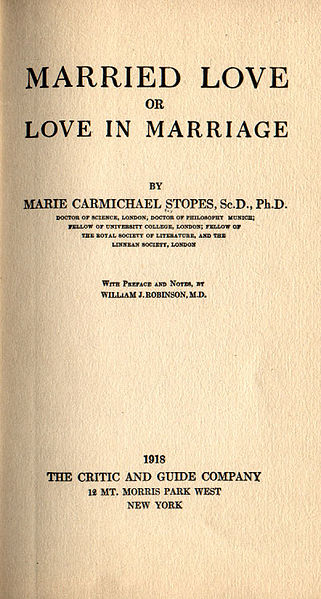

Like others girls of her class, she might have received some basic information regarding what used to be known as ‘the facts of life’ prior to her wedding, but nothing about the risks and dangers of sex. Lois Delmer (and she was doubtless not the only mother to make that choice) prefers to shield her daughter from all such unpleasantness, rather than warn her. In her mother’s eyes Lettice is ‘snowdrop-pure’, ‘pure as a dawn, lark-carolled,/in an unclouded May?’ This is how she wants her to be, and to remain: innocent, and as fresh and fragile as the posies Letty has put together for the ‘fallen women’ at Dr Delmer’s Special Hospital. Her fate, from which her mother will prove quite unable to protect her, will be no better than that of the flowers, unwelcome, inappropriate ‘wasted gifts’, that ‘lie among plimsolled feet’, ‘bruised by their fall’.

To have explained to her daughter why the flowers were so wrong was beyond Lois. Were it not for Lois’s objections, Dr Delmer would long ago have ‘talked plainly’ to his daughter, she would have understood the reasons for Flora’s hospitalization, and been spared the consequences of her own ignorance. His blinkered wife, who too easily confuses ignorance with innocence, loves her fond chats with Letty, but studiously avoids any difficult, or troubling conversation.

She couldn’t have confessed to her daughter, or even to her husband, how much she hated her regular Thursday visits to the hospital. Rendell Delmer is a good, Christian man, and like many good, strong men with a vocation to care (is Susan Miles’ thinking of her own husband the Reverend William Roberts?) he is unable to see that his family might not share either his generosity of spirit or his strength. It is at his suggestion that Lois unwillingly agrees to take in a recovering Special Hospital patient, one whose misdemeanors had left her not only with an unnamed venereal disease but an abandoned son, Derrick, who is to be traced and brought to join her. Their initial stay with the family is short and far from sweet, but Flora Tort and more particularly Derrick, will find their lives entwined with that of the Delmers to an extent that Rendell could not have foretold, or desired, and that he does not live to see.

Rendell’s brand of muscular Christianity does not admit resistance or much discussion, but he is not an unkind man and understands Lettice better than her wilfully blinkered mother. It is he who is concerned for her when Flora and Derrick are forced to leave, Flora to return to hospital and Derrick to live with the Delmers’ one-time laundress: he has injured Lettice in a fit of temper, his mother has gone back to her old ways, and both have been pilfering. Rendell has observed how his daughter’s ill-judged, but largely well intentioned overtures towards the small boy have been rebuffed, and is troubled, ‘She isn’t used to failure.’ Unlike her mother he has little faith in Lettice’s artistic or literary talents: like Lois, he hopes that she will marry early – what else is she fit for? – but rightly as it turns out, he has less confidence in the ‘understanding’ with Hubert’s old friend, Francis Conway.

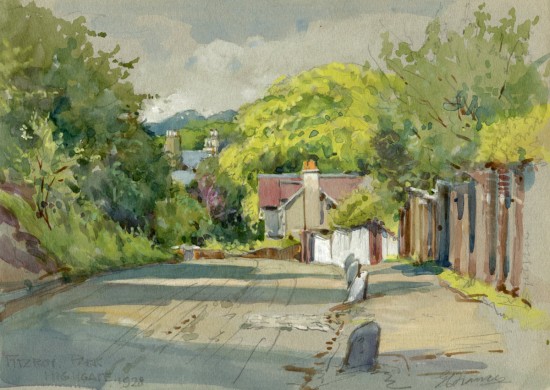

Miss Lettice, whom you used to live with once,

over at Highgate? Fitzroy Park, you know.’

Fitzroy Park 1920s by George Francis

Both parents, in their way, love Lettice (not so much that they don’t think twice about having her fill in when they are short of a maid!), but neither are, as we might say now, ‘there for her’ when she needs them, her father dead, her mother virtually silenced by a stroke. Her brother Hulbert, personally deeply disappointed by his sister’s failure to seal the understanding with Francis Conway (he clearly loves Francis and marriage to his sister would have kept him close for life), has been charged by his father with helping Letty. He means well, tries, but fails with tragic consequences.

So Lettice finds herself floundering in the world, in spite of early years in the bosom of a prosperous and essentially caring family, while Derrick, the child of a promiscuous single mother who doesn’t much care for him, finding his legs too skinny and unnerved by his squint, gradually replaces her in the now extended Delmer family, growing up to be clever, and kind, and most importantly, aware of the needs of others and conscious of the fact that his well-being and progress depend on this awareness. Insecure in his early years he builds his own security around him. One could say that he makes his own luck, in way in which Lettice proves quite unable, or unfitted (nature or nurture?) to do.

For Lettice was always selfish, in the sense that, while not deliberately unkind, she lacks empathy. The dark side of her innocence is a lack of imagination when it comes to the needs or emotions of others and Susan Miles makes this clear from the start. It is without a thought for what might please Flora or Derrick that Lettice plans the decoration of their rooms. Others will, of course, do the work, and when it doesn’t please Lettice, redo it – the old seamstress will gather where she had goffered and not complain (how bleak, by comparison, will Lettice find her hostel room in London, ‘… neat and comfortless,/ its curtains not from Liberty’s or Heal’s/ but from some cheaper shop that mimics theirs …’). Weakly Lois let’s her daughter have her way – ‘Letty will develop Flora’s taste/ not pander to it’ – and, ever indulgent, is lavish in her praise, not wanting, or daring to suggest that she think first of others’ tastes and needs, that she seek to understand rather to be understood. It is ultimately this failure to appreciate the needs of others, to be sensitive to their passions, or their intentions, good or bad, that will prove her downfall.

Miles places a cast of complex characters, a large cast for such a short novel, against a background of social upheaval, a new world in which class boundaries are shifting, expectations changing, for which a comfortable and cosseted upbringing may not be the best preparation. It will not be their own children who benefit from the security promised by ‘Foursquare House’, Dr and Mrs Delmer’s retirement home. That will be for another family.

History, luck, fate, the hand of God? Could things have gone differently for Lettice? Grimly and unpredictably her life mirrors Flora’s, even the opening hospital scene is revisited later in the novel, down to the smallest detail. But Flora is neither innocent nor ignorant and unlike Lettice she is not a victim. Her spiral, like her son’s, revolves upwards, while Letty’s spins horribly downwards: she meets the wrong people, makes the wrong decisions, acts on impulse and flawed intuition and, as if life had not hurt her enough, seeks comfort in inflicting further punishment on herself. Is the suffering redemptive? We are allowed to hope so. A chance encounter – luck for once being on her side – saves her life, a second effects some reconciliation with her family, a fresh path beckons as a result of an, unusually, unselfish impulse on her part – her own sorrows have, predictably, left her with little to give others. Her end is tragic, and haunting.