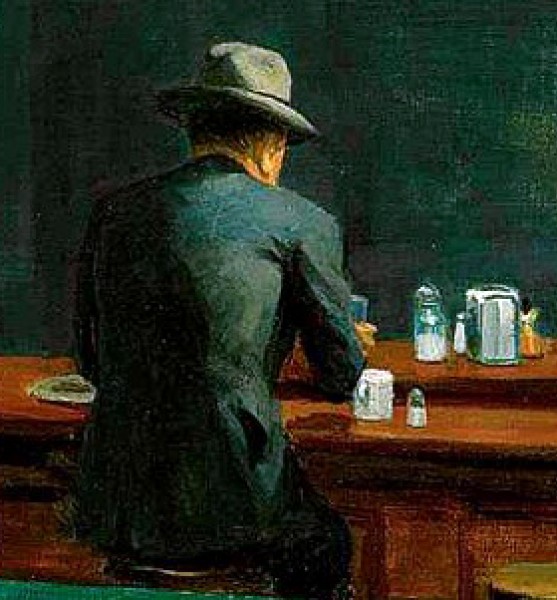

A young medical intern is driving from Los Angeles to Phoenix, Arizona, in a white Cadillac, borrowed from his mother. We surmise, but are not told, that he is young, because he refers to his younger teenage sisters, that he is a doctor because in the trunk (boot) he has stowed his medical bag, and from the car, conspicuous and conspicuously expensive, we infer that his family is comfortably off. We meet him a quarter of the way into his 420 mile journey to attend his niece’s wedding. He is leaving Indio, California, where he has had a minor encounter with a jalopy load of teenagers, which unsettles him more than one might expect, and a long wait at a drive-in for a bacon sandwich gracelessly served, which, surprisingly, troubles him barely at all.

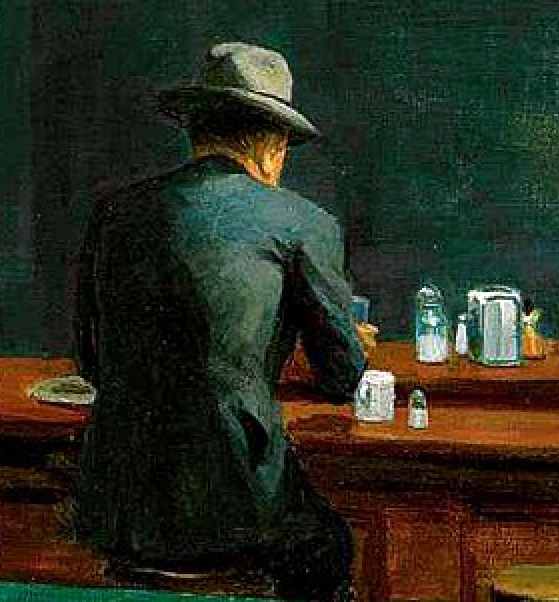

There are few cars on the interstate highway, it is early evening but still blisteringly hot as he heads into the desert. Way beyond walking distance from Indio, sheltering in the shadow of a tree, a young girl is hitching a lift. A kind, educated, professional man, from a good family, our young doctor, for whom, in just a few pages, Hughes has enlisted sympathy and admiration, does the right thing. To protect her from some other, potentially predatory, driver, he picks up a vulnerable, charmless teenager, who proves to be both mendacious and needier even than she first appeared. ‘I let my sympathy rule my judgement,’ he ruefully reflects later. Picking up strangers on empty roads is perilous, ‘he’d known it long before newspapers and script writers had implanted the danger in the public mind.’ Iris Croom, the name she gives, is trouble, and we are as keen as Dr Hugh Densmore to get her out of that Cadillac and onto a Greyhound bus; failing that, and it fails, to see her dropped off in Phoenix, so that our attractive, if somewhat paranoid, young doctor can join his relations for the celebrations.

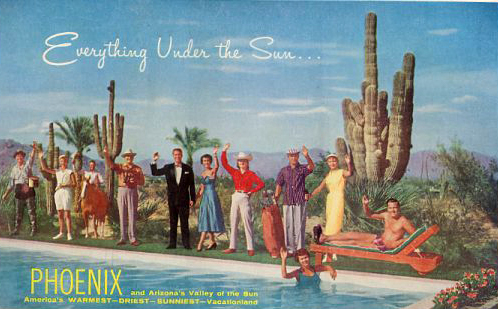

The family home in Phoenix is a large old frame house, with red roses climbing over the broad porch, and oleanders against the tall hedge. Clytie, Hugh’s niece, has chosen to be married ‘in the ancestral home, to walk down the long front stairway as her mother and her mother’s mother had before her.’ This is picture postcard America, prosperous middle-class, professional: his brother-in-law is a doctor, his father in insurance, grandfather a minister, Clytie and her cousins at or heading for good universities – far removed from Iris Croom’s dead-end life in Indio, abandoned by her mother to live with an uncaring feckless father.

Iris is no more than ‘a small memory far back in Hugh’s consciousness’, not quite erased; told that he has been booked into a motel to make room for the in-laws, he is relieved to know that, in the unlikely event that she were to spot the Cadillac, Iris will not be pursuing him at home. But the links in what he subsequently describes to himself as ‘a paper chain of circumstance cut from sympathy and too much imagination’ have already been joined. In a rear unit (‘there were no second-rate units’) at a luxury motel, Iris tracks him down, as he had feared she would. She is pregnant, he, regretfully, refuses to help, and sends her away.

Once again he has done the right thing. So why, when a girl’s body is found in the city canal, is he the prime suspect? The clues have been there all along. Hughes has planted them, but so subtly that in our haste to read on, they have been easy to miss. Why has Hugh been given a rear unit? Why was he so very anxious about giving her a lift? Why looking for a room the previous night at his regular stop, had ‘he hoped there’d be a vacancy tonight, you never knew. Sometimes even when the sign said there was one, the last unit had been rented just before you arrived’? Why had the official at the interstate inspection station ‘resented the big white Cadillac the moment Hugh drove up in it’? Why had he accepted such ungracious service at the drive-in? Why the paranoia? One word from a foul-mouthed police officer and the pieces fall into place. It is shocking and dramatic and if you haven’t read this brilliant book, log out now!

SPOILERS AHEAD

‘This guy says a nigger doc driving a big white Cadillac brought Bonnie Lee [Iris was lying about her name] to Phoenix.’ The first time I read The Expendable Man, I had to turn back to the beginning to check that I hadn’t missed mention of Hugh’s colour. Dorothy B Hughes, indirectly in her hero’s voice, has told us a lot about him, but not mentioned what is, but shouldn’t be, his most significant feature. He is everything we thought, clever, ambitious, kind, and so are his successful relations, and so is his niece’s elegant and beautiful roommate, Ellen Hamilton, from ‘one of the old Eastern families whose status went back to Revolutionary days’. But the ancestral home, with its wide porch and its long front stairway belongs not to a white family, as we had prejudicially assumed, but to an established African-American family. Hugh and his family and Ellen are black.

And that is why the police have come for Hugh. If we have wondered who the ‘expendable man’ might be, now we know.

Hugh is vulnerable, not because of age or poverty or wretched parenting like Iris/Bonnie, but because of the colour of his skin. A white girl has been murdered. She has been seen in a car with a black man. Why look further for the culprit? For the police, lazy and racist, further enquiries represent a waste of time and effort. The press is crying out for an arrest. No wonder Hugh asks himself, ‘How long before he’d be thrown from the sleigh to appease the wolves of discontent?’. The uncomfortable truth is that: ‘He was the wrong man to have played Samaritan, and he’d known it, known it there on the road and in every irreversible moment since.’

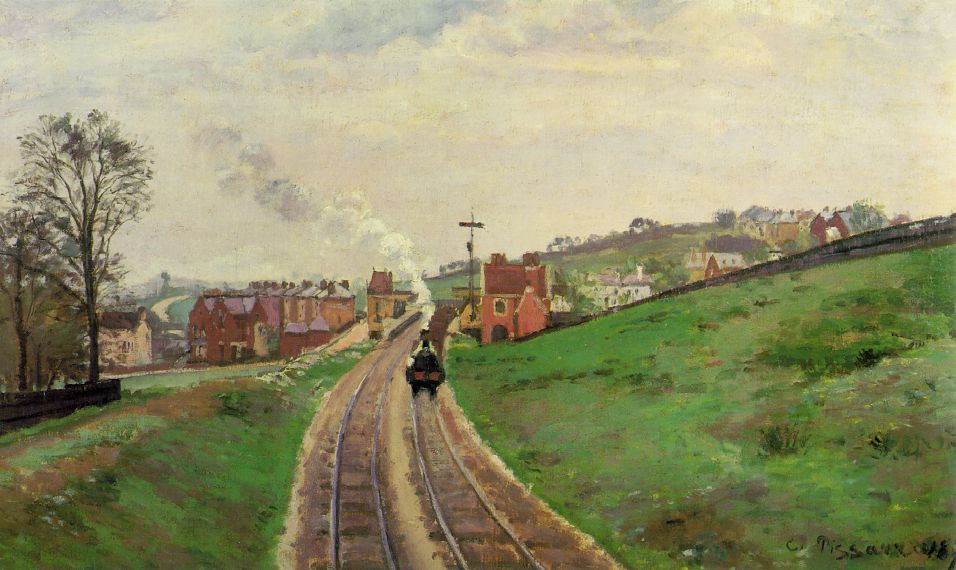

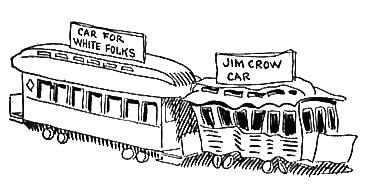

The Expendable Man was first published in 1963, the year of Martin Luther King’s ‘I Have a Dream’ speech, the year in which President Kennedy proposed civil rights legislation that would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964, pushed through by President Johnson, helped by the shock-wave of sympathy following Kennedy’s assassination. When Hughes was writing The Expendable Man, segregation was still enforceable by law in the South: the ‘Jim Crow’ laws (‘separate but equal’) covered schools, housing, employment, and transport, public lavatories, waiting rooms and restaurants.

‘This wasn’t the Deep South,’ Hugh reassures himself, ‘it was Arizona.’ Nor, although he does not specify this, was it liberal California, where Hugh’s immediate family had settled and where he has pursued his medical training. In most Western states, including California, there was no legislation. In the North-Eastern states segregation was forbidden by law (although de facto segregation existed in both housing and employment); but in Arizona, along with New Mexico, Kansas and Wyoming, racial segregation was ‘a local option’, not required but allowed. A contemporary blogger, writing about Phoenix in the 1960s, describes it as ‘culturally a Southern city’, which suggests that the ‘option’ was quite widely taken up.

Hugh’s grandparents would not have been unusual in owning their own home – in the 1920s, 75 percent of African-Americans living in Phoenix owned their houses – but their neighbourhood, though still relatively prosperous, would by the 1950s have been predominantly black. ‘Mortgage discrimination’ (African-Americans refused mortgages on homes in ‘Anglo’ areas) and rigid racial deed restrictions set by the Real Estate Board, forbidding the selling of homes to ‘members of any race or nationality, or any individuals detrimental to property values’, had ensured that. Racial drift completed the ghettoisation. Hugh’s brother-in-law, Edward, father of the bride, has his office in a building ‘housing two doctors, a dentist, an architect and a pharmacy. All Negro. The white tenants had moved out when the pioneer, the architect, moved in.’

But by the early sixties things were changing, albeit slowly and erratically. In this relatively short novel, with a small but vividly characterised cast, set over a period of less than a week, Hughes provides a snapshot of a city in transition. Hugh has observed the changes. When Ellen waits to take over his Motel unit, the receptionist explains, ‘We haven’t any other space unreserved right now’.

‘It was a lie and they all knew it was a lie, but there was no rancour among them. This clerk couldn’t cancel the system; her genuine friendliness was her contribution toward eroding it. Five years ago she wouldn’t have had a vacant unit; ten years ago she would have said, “We don’t take Negroes”, if any had had the courage or spunk to inquire.’

Change, but still some uncertainty: when Hugh decides to hide himself away in a cinema he finds that ‘he didn’t know what the current rules were for seating but, remembering childhood, he took a seat in the balcony.’ That he does this without rancour strikes us, fifty years on and from across the pond, as rather surprising, but reflects the fact that this is the world in which he has grown up, while at the same time confirming his rooted self confidence – ‘He, Dr Hugh Densmore, product of his heredity and environment, sufficiently intelligent and well-adjusted to his mind and body and colour and ambition.’ – which he knows he must defend, and which will be, viciously and crudely challenged.

Ringle and Venner, the police officers investigating, if that’s not too generous a word for an instant assumption of guilt, operate by the old rules, preferring to believe ‘their own’. Even when ‘their own’ is poor Iris’s violent boyfriend, his word is worth more than ‘a dark alien stranger’, however well educated, and well connected. For a moment at the wedding celebrations Hugh wishes that Ringle and Venner could have been looking in: seeing how there was no segregation with Clytie’s university friends and her husband’s Air Force crowd, ‘they might realise that poor shoddy little Iris couldn’t have been the outworn cliché of sexual interest to Hugh.’ But, as the novel draws to a close – no spoilers – he is compelled to accept that ‘the Venners would not be changed in their generation’. Looking at recent television footage of police violence coming out of the United States, that estimate seems wildly optimistic.

But Ringle and Venner are low down on the law enforcement ladder. Higher up is the Marshal, whom we sense at heart prefers the old ways, but is anxious to keep things legal and clear, without taint of prejudice. He doesn’t want a lot of do-gooders weighing in, and furthermore he has political ambitions: public opinion is moving towards civil rights, and that’s where he’s hitching his wagon.

Until this month probably the best known, and revered, American literary legal hero was Atticus Finch, but Harper Lees’s recently published sequel/prequel to To Kill a Mockingbird has revealed him to have feet of clay. Finch was a racist after all. Not so Skye Houston, the white lawyer who takes on Hugh’s case and who, perhaps not coincidentally, lives on Mockingbird Lane. Not only is Ellen Hamilton beautiful and intelligent her father is a Washington judge. It is he who suggests Skye, and Skye who insists on first names – he is the future. Skye Houston has made his reputation, and his fortune; unlike Marshal Hackaberry he is able to do the right thing for the right reason.

Even with Sky Houston at his back, Hugh must do his own investigating (helped, of course, by the brave and resourceful Ellen – think Agatha Christie’s Tuppence, Durbridge’s Steve or Dorothy Sayer’s Harriet Vane). A desperate search for Iris’s killer or killers leads him to some seamy areas of Phoenix, a world away from the Densmores and the Hamiltons, where Hughes introduces us to some unsavoury characters, brilliantly, and not wholly unsympathetically, drawn, brought down not by colour but by poverty, and inadequacy, whose moral compasses have long ago been ditched, expendable in their way, but protected by the colour of their skin, for as long as the ‘Venners’ survive .

This page-turning thriller carries a powerful but non-polemical message: small details and subtle hints describe what Hugh Densmore calls ‘the tedious inching forward’ towards racial equality. It also offers a rare picture for the period of middle-class African-American life, rarely touched on by white novelists.

In an attempt to fill in the many gaps in my knowledge about the civil rights movement in the United States, and in particular in Arizona, I came across an article by Phoenix Municipal Court Judge Elizabeth Finn who grew up in Phoenix in the 1950s. She describes the dramatic breakthroughs that were made by lawyers working pro bono and by ‘just plain citizens, of all races and creeds, giving their time and effort to a cause they cherished’, noting particularly the important role played by women, who were not worried about offending people in power and did not hesitate to express their feelings about the fundamental issue of civil rights.: women, perhaps, like Dorothy B. Hughes, who had lived most of her life in New Mexico (which borders on Arizona) and took the same equivocal stance on segregation.