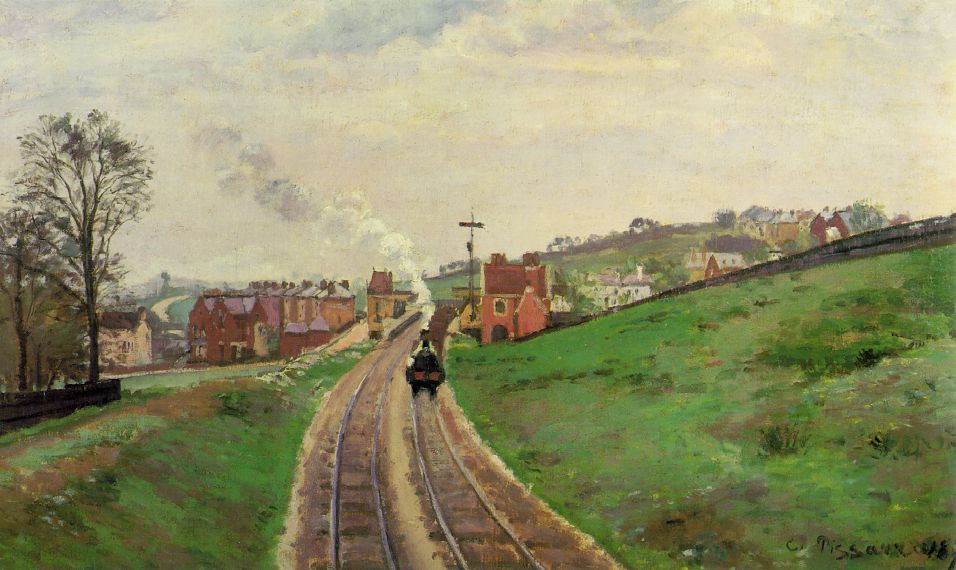

The arrival of the first trains from Victoria to Bognor, considered by some to have lowered the tone of this previously exclusive resort, would have encouraged London couples to choose it for their honeymoon. Since the visit of the future George V and Queen Mary in 1900, the pier had been completed – good for wet and windy days – and a flurry of house building begun in the 1880s had continued. There would have been no shortage of seaside landladies to welcome the newly-weds.

The Stevens find ‘Seaview’ in an advertisement, the newly acquired property of Mr and Mrs Huggett, ‘well done up and scrupulously clean’. Built in 1890, just ten years before the Stevens own house in South London, it owes its name to the fact that ‘from the lavatory window you could see the top of a lamp post on the front’. The honeymoon is lovely, both agree on that, and one fortnight in September leads on to another and another, with one child, then two, then three. Other resorts are considered – Brighton, Bexhill, Lowestoft – but Mr Stevens dislikes change, and Mrs Stevens defers to Mr Stevens, in all things. She is younger, less educated, and of a lower social class, carelessly, to the dismay of her husband, dropping aitches when over-excited, and inclined to pronounce really as ‘reely’.

The Fortnight in September is a scrupulously and delightfully detailed account of the twentieth of these holidays, the fortnight around which Mr Stevens regularly pivots his calendar, and which his wife finds a burden, sometimes a nightmare. There is an uncomfortable truth to the cliché that ‘a holiday takes you out of yourself’, and Flossie Stevens who is content with her suburban life, at home in Dulwich, where the roads are long and friendly and dotted with people she knows, doesn’t want to be taken out of it. ‘At home the children were hers: they loved her: came to her in everything. At Bognor, somehow they drew away from her – became different. If she paddled, they laughed at her: saying she looked so funny. They never laughed at her at home.’ For her husband Going Away Eve is the happiest evening of the year, but not for her.

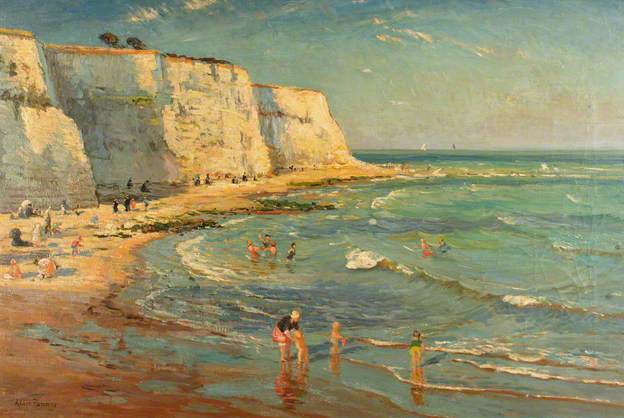

If she is ‘almost elated’ at the start of this particular fortnight in September, it is because ‘the holiday brought such joy to the others’, her husband, Mary and Dick, grown-up and close to leaving the nest, and little Ernie. She will watch as they shed their work clothes, hats and ties, heavy shoes and thick stockings, ‘to join the bareheaded, open necked, bare legged crowd’ but she has no holiday wardrobe, ‘she had tried without success to think of something she could do to make herself look different – but neither she nor the family could think of anything for her to put on or take off.’ She tried white sandshoes once but they made her insteps ache, and she feels uncomfortable without a hat. Sherriff is touchingly sensitive to Flossie’s unease.

Every year the journey fills her with dread: top of her fear list is the change of platforms at Clapham Junction, from which might ensue the loss of the trunk, or of her husband (this had happened once, briefly); this is closely followed by the possibility of a fellow passenger feeling faint (once, in nineteen years) or having ‘some kind of fit’ (similarly, once), and, more realistically their daughter Mary being sick (regularly as a child, but she is nearly twenty and those days are over). Mr Stevens is no less imaginative when it comes to potential disaster. The ten minutes allowed to walk from Corunna Road to Dulwich station, following the porter trundling their trunk (what a fascinating detail), could prove insufficient were a lady to faint, or accidentally fall down across their path, require care, maybe a policeman, or an ambulance, draw a crowd. They would miss the train, then the connection, and would have to go home and wait an hour in their hats and coats. Vividly he likens it to ‘breaking open and waiting in the tomb if you missed the train back from a funeral’. Manfully, paternally, he conceals his fears. For the fortnight in September he is in charge. The family will follow the marching orders he has drawn up, and refined over the years. Pre-departure tasks have been allocated and ticked off.

He rises to the challenge of Clapham Junction, to the delighted relief of his wife and his own satisfaction, a Pooterish smugness, reminiscent of Edgar Hopkins in The Hopkins Manuscript,Persephone Book No 57, which Sherriff delights in describing and gently pricking: ‘He was conscious of it – this instinctive power – leadership, he supposed it was. His ordinary life gave little chance to draw upon it. It required a Clapham Junction or a burst pipe to bring it to the surface.’ The train journey always ‘put down as a doubtful quantity in the sum of human happiness’, is controlled as far as possible, not always to his total satisfaction – fellow passengers can prove noisy or too numerous – but the familiar landmarks provide reliable pleasure plotting the distance from the slights and disappointments of his daily life. With a cinematic eye for passing detail (little surprise that he would later become a Hollywood script-writer) Sherriff puts his reader in a window seat, pointing out the family cat on the tool shed, the inexplicable detritus along the railway bank, the broadening Arun river, the first seagull, harvesters and housing developments, while allowing his characters vividly to present themselves through their various reflections and in their own distinctive voices. The journey takes up almost half the novel, and isn’t a page too long.

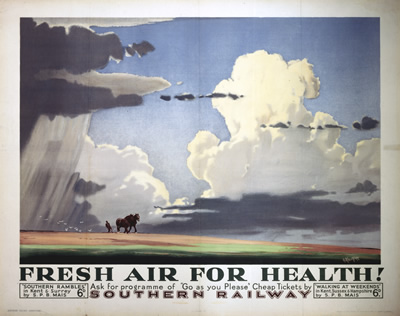

Bognor is seventy miles from London, no more than three hours by train in 1930, but the distance is everything. It’s not physical change they go for: what they love about Bognor is that it stays the same: the shop with the sandshoes hanging outside, the shop with the fat rods of rock, and the fish shop, the toyshop and the postcard shop, ‘where you bought the little folding cards that let down a zigzag strip of pictures’. The change they look for, and find, is in themselves, even Flossie during her quiet happy evenings alone with her needlework and a ‘medicinal’ glass of holiday port. ‘The man on his holidays’, reflects Sherriff, ‘becomes the man he might have been, the man he could have been, had things worked out differently.’

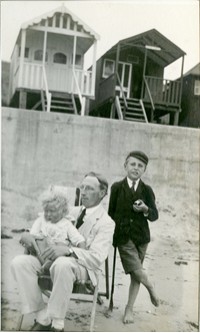

Mr Stevens’ long solitary walks, longer since the early days, thanks to the introduction of buses, give him time and space to reconcile himself to what he is accustomed to thinking of as his failures, to accept, for a while, his limitations, and then, taking a different turning, to dream again, to plan ‘the things he would do when his stroke of luck came.’ We do not need reminding that he has walked these paths twenty times over, dreaming the same dreams, no more changed than the shops or the pub on the corner where he enjoys his nightly holiday drink with his holiday friends. The fortnight doesn’t alter him, but it gives him a rest from himself. After a day or two ensuring that the right impression is made, on the beach and at the bar – ‘no buckets and spades, yachts or even kites on your first day’s visit to the sands’, and no going to the Clarendon Arms when tired after the journey – he can begin to relax, to enjoy a little (secret) flirtatious banter with the buxom barmaid, to find his inner child playing beach cricket, and allow himself to be photographed wearing ten-year-old Ernie’s little striped hat.

Less attractively, in micro-managing the holiday, he is able to enjoy a degree of control way above anything he could aspire to in his working life. Not that he sees it that way; ‘It was not that he enjoyed bossing people and running the show: it was simply that he knew how necessary it was to have some general scheme if every hour of the holiday was to be properly enjoyed.’ Part of his wise plan, leaving nothing to chance, is to timetable days off. This suits him very well, and as it turns out suits the family, freeing them from his boisterous calls to action, driven by a longing to revive the holiday spirit of previous years when David and Mary were still children, a futile longing which blinds him to the more grown-up benefits that the two of them, unexpectedly, derive from the fortnight. David’s own long walk gives him time and space to re-assess his past and consider his future, to work out a plan that will liberate him from his dead-end job, while his older sister, thanks to a little judicious fibbing, gets the opportunity to wear her best holiday dress for a slightly illicit meeting with a new found girlfriend, followed by an even more illicit meeting with a young man. Granted a little more freedom, what might have been the last family fortnight in September may prove not to be.

The shadow of the older children wanting to go away on their own in future had rather hung over the holiday, as does the possibility, the likelihood in fact, that Mrs Huggett won’t be taking in summer visitors for much longer: the house, so sparkling and bright 20 years before, has grown shabby, Molly, the maid-of-all-work has aged and her cooking has deteriorated. Mrs Huggett’s regulars are deserting, hotels and bungalows and day trips are defeating her. But the Stevens will return, they will pre-order the crate of dinner ale and the two jars of ginger beer, Flossie will take her list to the local shops, they will protect their exposed skin with olive oil and look forward to the military band, ‘much smarter than the ordinary kind’, and reserve a bathing hut with a balcony in good time.

The period detail is fascinating, and The Fortnight in September is full of humour, rarely unkind. For all his bossiness, and old-womanish fussiness, we can believe that Mr Stevens is doing his best to create the perfect holiday. Only once does Sherriff put poison in his pen, to describe Mr Stevens’ rich clients in their newly and very, very expensively built villa, with rolling lawns and dying trees: ‘his eyes, nose and mouth were crowded very close and rather meanly together considering the large amount of unused face that lay around them’, while ‘she looked as if she had been boiled in too much water, then artificially flavoured’. We have met those people.

And, although we no longer travel with trunks, or change at Clapham Junction, except perhaps to catch an Easy Jet plane from Gatwick, and the beach huts have all been sold for the price of small houses, and our photographs are on our phones. not waiting in envelopes to be collected from the chemist, the anxieties, delights and disappointments of the family holiday haven’t changed that much. Down to the ‘whisper that comes from the little stream of sand that falls from your shoe as you undress on the night you return once more to your bedroom at home’, Sherriff gets it so right. Search Google for ‘holiday + psychology’ and you will find pages and pages of advice from ‘Stress Management During the Holidays’, ‘Strategies for Surviving the Holidays’, to ‘Summer Break or Summer Break-up’ and worse. Sherriff wonders in his introduction why his novel ‘took off’, which it did, spectacularly, and modestly suggests that it was because it was ‘easy to read’. It is easy to read, but much more importantly it is beautifully observed, with no less insight than shelves of holiday-psychology articles.