When Winston Churchill’s American mother, Jennie Jerome, crossed the Atlantic for the first time in 1867, the expected journey time would have been about ten days. Thirty years earlier it might have taken twenty days or more and thirty years later, with a good following wind, it would take as little as five. Iron hulls had replaced wooden ones, steam engines and screw propellers had replaced paddle wheels and sails. Average passenger capacity had increased from two hundred to fifteen hundred. Crossings were frequent, regular and, for those who could afford it, comfortable.

The Jeromes, Jennie, her sisters Clara and Leonie, and their mother, were heading for Paris and later London, where they would find the entrée into the higher échelons of society which had evaded them in New York. Leonard Jerome’s fortunes fluctuated, but when he was rich he was very, very rich, and he shared his wife’s ambitions for their daughters. His money, unfortunately, was of the wrong sort. Only old money secured a place among ‘The Four Hundred’, the élite of New York Society, presided over by Mrs William Backhouse Astor – the number being, anecdotally, based on the limitations (if that is the appropriate word) of Mrs Astor’s ballroom.

Parisian society, and the English aristocracy, offered a warmer welcome to American girls described by the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, as ‘livelier, better educated and less hampered by etiquette … not so squeamish as their English sisters and better able to take care of themselves.’ And, he might have added, in the main richer. These ‘dollar princesses’ would be the answer to a prayer for a land-owning class whose land was producing diminishing returns. The same advances in marine engineering which had speeded the Jerome girls on their way had transformed transatlantic merchant shipping. Imports of cheap American grain, and meat (the new refrigerators that so conveniently chilled champagne for the first class passengers could also ensure the delivery of fresh carcases to British butchers) had a devastating effect on the incomes of England’s landed aristocracy. Farm rents had to go down, and with them allowances for younger sons or brothers and dowries for daughters or sisters. Dwindling funds led to the collapse of cottages and stately homes. Add a gambling habit, drinking or expensive womanising to the mix and the most valuable remaining asset was a title. The marriage between Jennie Jerome and Lord Randolph Churchill, younger son of the Duke of Marlborough, was the result of a whirlwind romance and not a commercial transaction; but she so loved the title that after Randolph’s death, and divorce from her second husband she changed her name back by deed poll to Lady Randolph.

Jennie’s father had provided a marriage settlement of £50,000, yielding an income of £2000 a year (£140,000 today), which was deemed insufficient by the Marlboroughs, all the more so as Leonard, wisely, ensured that half the income was paid directly to his daughter. American law was many years ahead of English law: the Married Women’s Property Act had been enacted in 1848; English women would not secure the same rights until 1882.

Her title had not been cheap, but cheaper by far than that of her nephew’s title. When, ten years later, Consuelo Vanderbilt married the future Duke of Marlborough, she brought with her $2.5 million ($65 million today). It has been estimated that between the 1870s and 1914, four or five hundred American heiresses married into the British aristocracy, filling the depleted coffers with the equivalent of £1 billion. Yet ‘cash for titles’ was not a recipe for marital harmony. Consuelo Vanderbilt’s marriage was unhappy from the start: the Marlboroughs separated in 1906 and divorced in 1921. The Churchills’ ‘love match’ cooled rapidly after the birth of Winston, although Jennie remained a loyal political wife, and was with him as he lay dying (most probably from syphilis). Anne Sebba has written a wonderful biography of Jennie Churchill, and in her preface to The Shuttle convincingly links it to the story of Jennie and Lord Randolph, with which Frances Hodgson Burnett would most certainly have been familiar: such marriages were widely reported.

Five years older than Jennie, born in Manchester in 1849, Burnett made her first Atlantic crossing, in the opposite direction, in 1865. She was fifteen and would come to know the ‘shuttle’ well, making the journey more than thirty times in her lifetime, closely observing society at all levels in England and in America, like Edith Wharton, Trollope and Henry James fascinated by the meeting of the two cultures. Old money (jn diminishing supply) meets new (abundant); lazy confidence, based on history and a calcified class system, confronts the ‘can-do’, forward-looking confidence of the new country, in which the social ladder has not been pulled up. The Americans, however rich and clever, and on their own ground sophisticated, show a certain trusting innocence – Burnett calls it ingenuousness – which can leave them vulnerable to the cynical, low cunning of the worst of Englishmen. Financially ‘cash for title’ could prove an expensive failure, emotionally it could prove a disaster.

Just such a near disaster is at the heart of The Shuttle. Burnett wrote to a friend that she was ‘not in the least anti international marriage’, only against ‘a certain order of particularly gross, bad bargain’. She weaves a complex and compelling plot around the consequences of just such a bad bargain. Reuben Vanderpoel’s money, like Leonard Jerome’s and William Vanderbilt’s, is of the wrong sort. In one of the early international unions, he marries his older daughter, ‘pretty little simple’ Rosalie, to Sir Nigel Anstruthers, an evil-tempered, arrogant, impoverished Englishman, with an equally unpleasant mother, a crumbling estate, and a past that he prefers to conceal. Vanderpoel is a loving father, in no way desperate to find a match for his daughters, but ‘the republican mind had not yet adjusted itself to all that such alliances might imply. It was yet ingenuous, imaginative and confiding in such matters’. Like many others the Vanderpoels were easily seduced by the promotional image of ‘a baronetcy and a manor house reigning over an old English village and over villagers in possible smock frocks’. Only eight year old Bettina sees through Sir Nigel’s assumed charm: ‘I loathe him … He’s stuck up and he thinks you are afraid of him and he likes it.’ Sir Nigel detests her.

While English girls rarely emerged from ‘the schoolroom’, and both boys and girls ‘were decently kept out of the way and not in the least dwelt on except when brought out for inspection during the holidays and taken to the pantomime’ – Burnett’s pen is as sharp as it is in The Making of a Marchioness (Persephone Book No. 29) – American children joined fearlessly in adult conversation. Although she lacks the adult words, Rosalie’s younger sister has seen Sir Nigel for what he is, ‘an unscrupulous, sordid brute, as remorseless an adventurer and swindler in his special line, as if he had been engaged in drawing false cheques and arranging huge jewel robberies, instead of planning to entrap into a disadvantageous marriage a girl whose gentleness and fortune could be used by a blackguard of reputable name.’ Betty is a force to be reckoned with, unlike her non-too-bright malleable sister, and indeed unlike her father, a kind man, who may be a shrewd businessman but strikes the reader as a poor judge of character. The Anstruthers’ family solicitors, we later learn, had similarly concluded that Rosy’s father’s ‘knowledge of his son-in-law must have been limited, or that he had curiously lax American views of paternal duty.’

Burnett is remarkably forgiving of Reuben Vanderpoel’s ingenuousness. She allows him a period of sorrowful reflection many years later, when Betty, now grown-up, has already taken matters into her own strong hands. ‘The memory of that marriage had been a painful thing to him, even before he had known the whole truth of its results. The man had been a common adventurer and scoundrel, despite the facts of good birth and the air of decent breeding.’ Reuben fears even for Betty: ‘… no man knows the thing which comes, as it were, in the dark and claims its own – whether for good or evil. He had lived long enough to see beautiful strong-spirited creatures do strange things, follow strange gods, swept away into seas of pain by strange waves.’

Frances Hodgson Burnett herself had learned some cruel lessons from her second marriage to her long-time lover Stephen Townsend. They married in February 1900, by May she is already referring to him as a blackguard and a blackmailer, to which she would later add a liar and bullying coward, complaining of his insistence on her ‘duties as a wife’, which included ending her acquaintance with anyone who did not admire him, and making over all her property to him. In April 1901 she insisted on a separation. Nigel Anstruthers is a darker version of Stephen, with even more extreme views on wifely duties, and crueller and more devious ways of enforcing them, the most cruel of all being isolating Rosy from her family so that she felt herself abandoned by them, and they by her. ‘If you shocked, bewildered or frightened her with accusations, sulks or sneers, her light innocent head was set in such a whirl that the rest was easy.’ Time, a little effort and any number of lies, which came easily to him, would ensure that Rosy’s money, protected by American law, became his money, as, by English law, he, and his scheming mother, believed it should rightfully have been. Only Betty’s persistence, strength and courage can rescue Rosy.

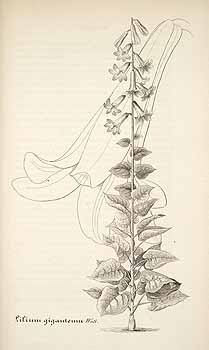

Bettina Vanderpoel had long ago proved herself the cleverest and most promisingly handsome as well as the richest at her ‘ruinously expensive school’, where she was educated ‘with a number of other inordinately rich little girls, who were all too wonderfully dressed and too lavishly supplied with pocket money’ (Burnett loves the Americans but she is not blind to their faults, and paints a vivid and keenly observed picture of their excesses). At twenty she proves to be one of the girls so admired by the Prince of Wales, lively, educated and well able to take care of herself, and her sister and her nephew, as well as the needy and the sick in the village, the house and most importantly, and symbolically, the garden at Stornham Court. With the help of a sympathetic gardener, Kedgers (one of Burnett’s charming ‘walk-on’ parts), Betty, like Mary Lennox in The Secret Garden, brings a neglected, overgrown garden back to life – the same garden, in fact, as both were based on the garden at Frances Hodgson Burnett’s house, Maytham Hall in Kent, where she lived with Stephen and began writing The Shuttle.

‘Grow them, Kedgers, begin to grown them,’ said Miss Vanderpoel. ‘I have never seem them – I must see them.’

The Shuttle brilliantly interweaves two narratives of two very different American sisters, and two very different titled Englishmen, one a villain with no redeeming features, the other a strong, complicated, romantic hero who wins our hearts as swiftly as he wins Betty’s – but no more of him, the story is far too good for spoilers! Suffice to say that in this stark indictment of late Victorian England, where good people are more likely to be found at the gates of the rich (or not so rich) man’s castle than inside, Mount Dunstan is a rare shining example of a man with a noble heart to go with a noble title.

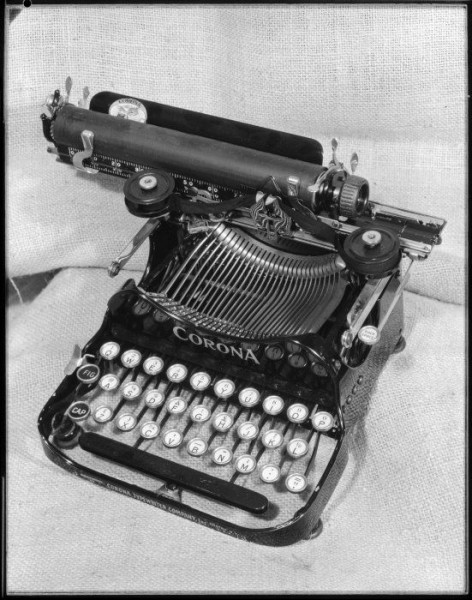

There are good Englishmen, but Burnett clearly believes that the English had more to gain from the shuttle than the Americans, and not only financially. The Vanderpoel sisters and others like them brought their fortunes, but not all Americans made the shuttle in first class. Many travelled steerage. G.Selden, is a delightful character and vital intermediary in the plot, who arrives with only the clothes on his back, a sales catalogue, a sample typewriter, and a bold charm, uninhibited by old world social conventions and free ‘from the insular grudging reserve’. Like Betty, he is confident that he can move obstacles, and like her, he is uncowed by England, his ‘nobles’, Pierpoint Morgan and W.K. Vanderbilt, being in his mind entirely parallel ‘with the heads of any great house in England’.

Frances Hodgson Burnett indentified increasingly with the New World. By the time The Shuttle was published in 1907, she had already become an American citizen. The success of the novel, $38 thousand dollars in US royalties in the first three months , enabled her to buy a plot of land at Plandome, Long Island, overlooking Manhasset bay, and build an Italianate villa, with a colonnade and a balustraded terrace. It was there that she died, not quite sixty years after her first ‘shuttle’, from Liverpool to Quebec.