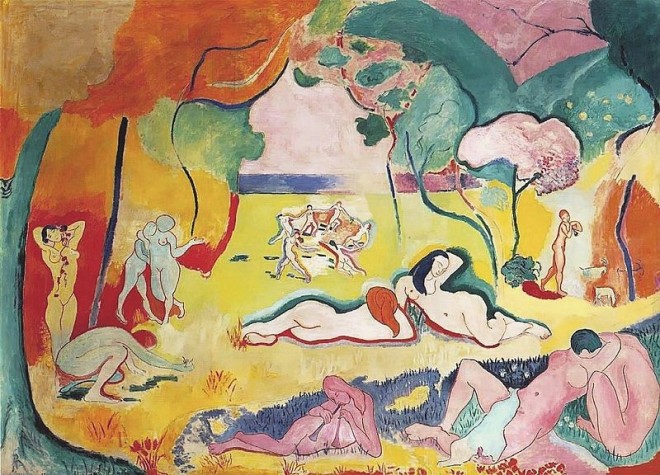

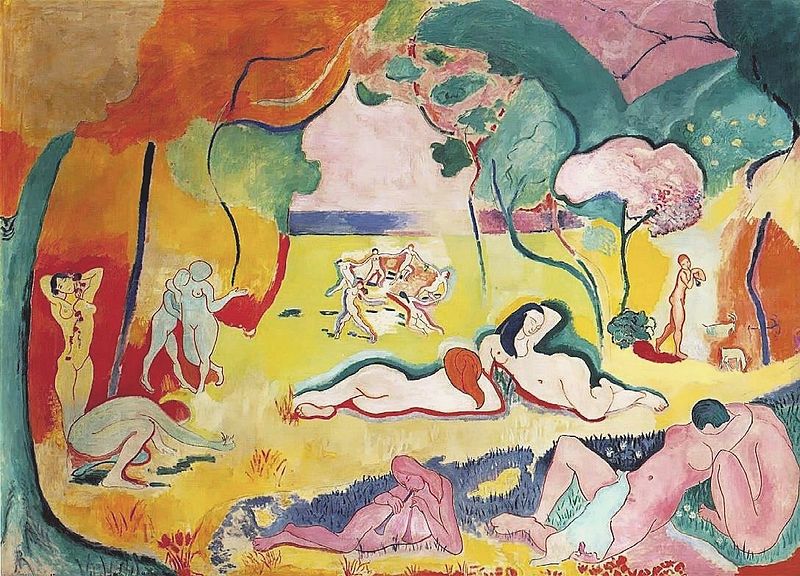

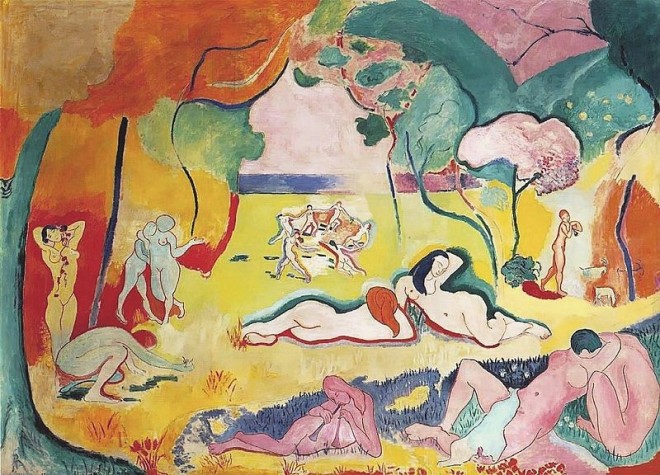

First shown at the Salon des Indépendents in 1906, Le Bonheur de Vivre seemed incomprehensible. It was greeted, recalled Matisse’s first dealer Berthe Weill, with “an uproar of jeers, angry babble and screaming laughter. . . . ” Yet in this painting Matisse had achieved a new kind of serenity, a harmony of unexpected elements, that he would draw on throughout his career’ (quoted here). ‘It is a large-scale painting (nearly 6 feet in height, 8 feet in width), depicting an Arcadian landscape filled with brilliantly coloured forest, meadow, sea, and sky and populated by nude figures both at rest and in motion. As with the earlier Fauve canvases, color is responsive only to emotional expression and the formal needs of the canvas, not the realities of nature. Matisse used a landscape he had painted in Collioure to provide the setting for the idyll, but it is also influenced by ideas drawn from Watteau, Poussin, Japanese woodcuts, Persian miniatures, and 19th century Orientalist images of harems. The scene is made up of independent motifs arranged to form a complete composition’ (quoted here).

First shown at the Salon des Indépendents in 1906, Le Bonheur de Vivre seemed incomprehensible. It was greeted, recalled Matisse’s first dealer Berthe Weill, with “an uproar of jeers, angry babble and screaming laughter. . . . ” Yet in this painting Matisse had achieved a new kind of serenity, a harmony of unexpected elements, that he would draw on throughout his career’ (quoted here). ‘It is a large-scale painting (nearly 6 feet in height, 8 feet in width), depicting an Arcadian landscape filled with brilliantly coloured forest, meadow, sea, and sky and populated by nude figures both at rest and in motion. As with the earlier Fauve canvases, color is responsive only to emotional expression and the formal needs of the canvas, not the realities of nature. Matisse used a landscape he had painted in Collioure to provide the setting for the idyll, but it is also influenced by ideas drawn from Watteau, Poussin, Japanese woodcuts, Persian miniatures, and 19th century Orientalist images of harems. The scene is made up of independent motifs arranged to form a complete composition’ (quoted here).

‘Rest Centre and Communal Feeding’ is by an unknown artist, it’s in the archive of the WRVS, now

‘Rest Centre and Communal Feeding’ is by an unknown artist, it’s in the archive of the WRVS, now

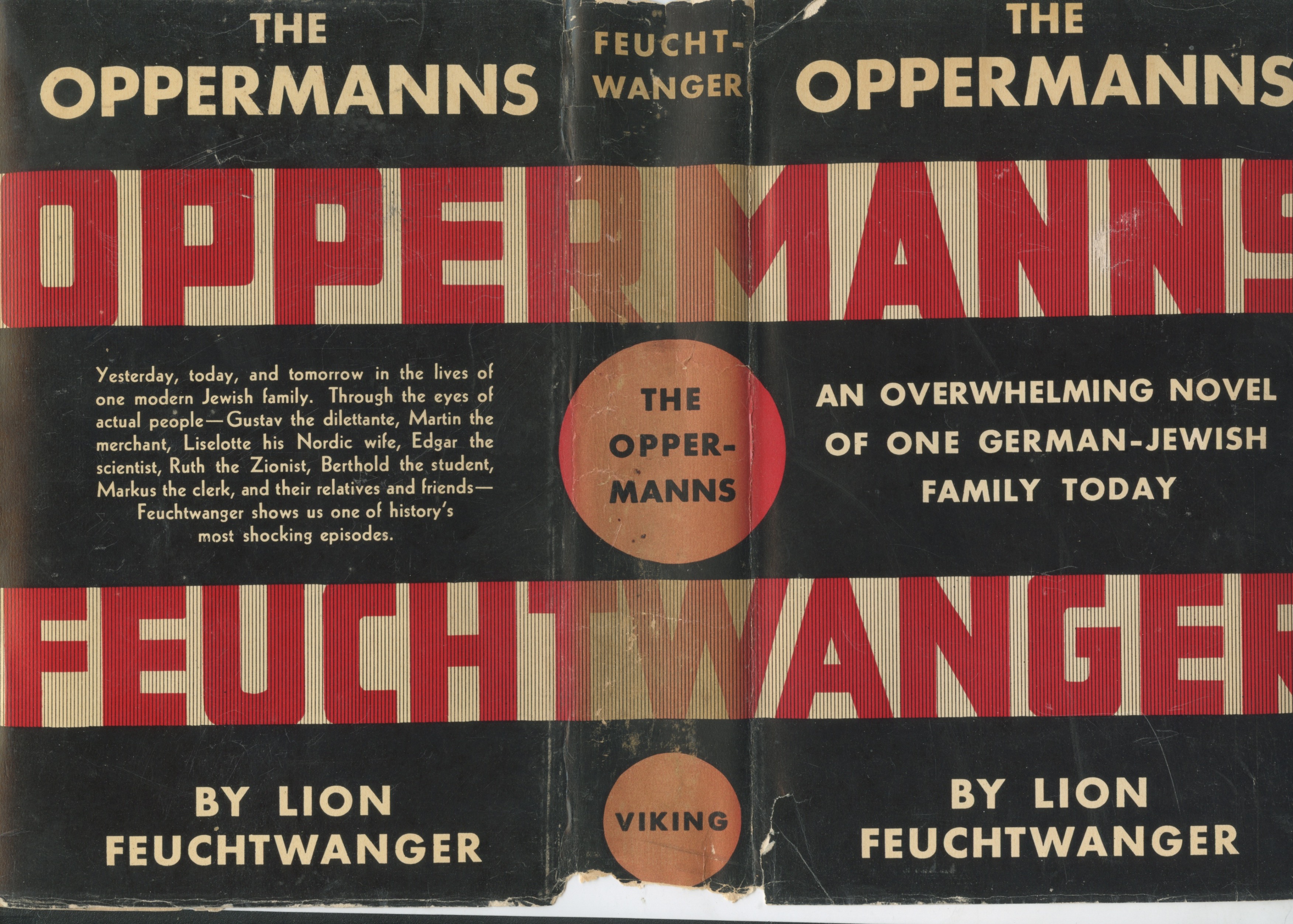

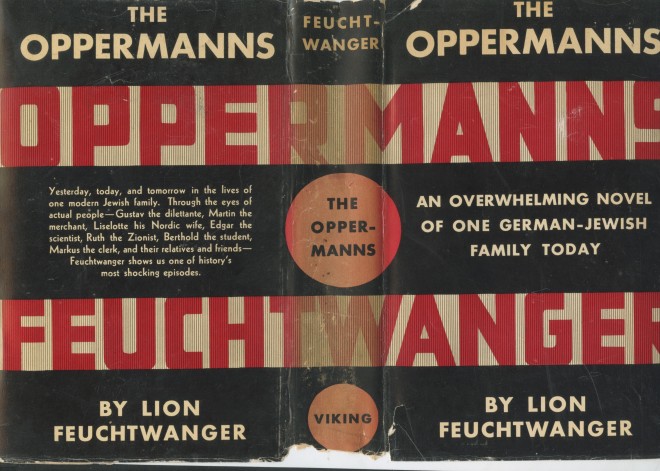

This is the original jacket for the American edition of The Oppermanns: the text describing the book is now up on our website

This is the original jacket for the American edition of The Oppermanns: the text describing the book is now up on our website

The BBC documentary is called Becoming Matisse and ‘tells the tumultuous story of his early life. Matisse (b. 1869) picked up a paintbrush at the late age of 21, and the next 15 years saw him turn his back on the bourgeois aspirations of his parents and teachers’ (

The BBC documentary is called Becoming Matisse and ‘tells the tumultuous story of his early life. Matisse (b. 1869) picked up a paintbrush at the late age of 21, and the next 15 years saw him turn his back on the bourgeois aspirations of his parents and teachers’ (

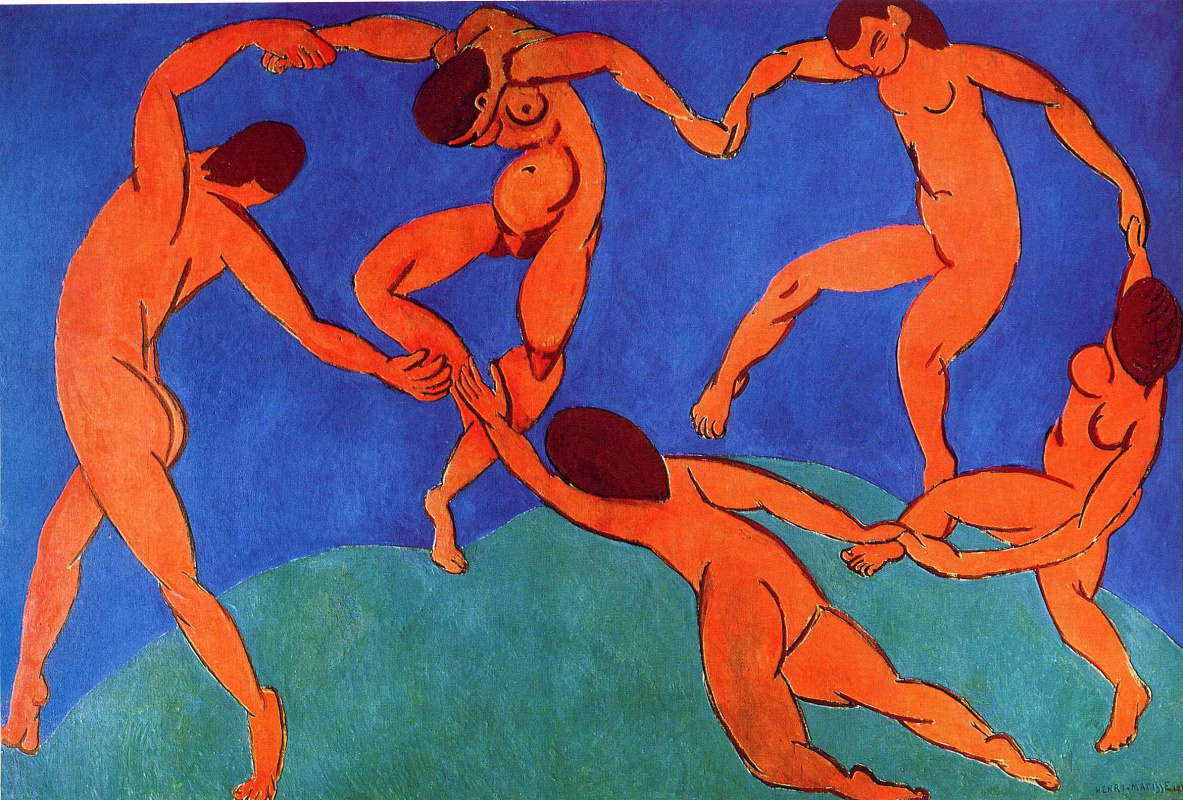

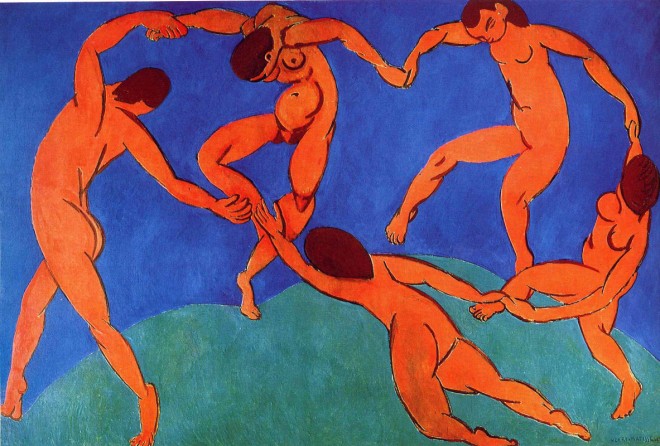

The Dance (1909) is an ode to life and has become an emblem of modern art. ‘It was commissioned with its matching painting Music by the influential Russian collector Sergei Shchukin. Characterised by its simplicity and energy, this ecstatic bacchanalia left a lasting mark on 20th-century art. Dance was painted at the height of the Fauvism aesthetic and embodies the emancipation from Western art’s traditional conventions of representation. It can be seen at the Hermitage in St Petersburg.’ ( In 1909 Virginia Woolf was 27. She kept

The Dance (1909) is an ode to life and has become an emblem of modern art. ‘It was commissioned with its matching painting Music by the influential Russian collector Sergei Shchukin. Characterised by its simplicity and energy, this ecstatic bacchanalia left a lasting mark on 20th-century art. Dance was painted at the height of the Fauvism aesthetic and embodies the emancipation from Western art’s traditional conventions of representation. It can be seen at the Hermitage in St Petersburg.’ ( In 1909 Virginia Woolf was 27. She kept

First shown at the Salon des Indépendents in 1906, Le Bonheur de Vivre seemed incomprehensible. It was greeted, recalled Matisse’s first dealer Berthe Weill, with “an uproar of jeers, angry babble and screaming laughter. . . . ” Yet in this painting Matisse had achieved a new kind of serenity, a harmony of unexpected elements, that he would draw on throughout his career’ (quoted

First shown at the Salon des Indépendents in 1906, Le Bonheur de Vivre seemed incomprehensible. It was greeted, recalled Matisse’s first dealer Berthe Weill, with “an uproar of jeers, angry babble and screaming laughter. . . . ” Yet in this painting Matisse had achieved a new kind of serenity, a harmony of unexpected elements, that he would draw on throughout his career’ (quoted