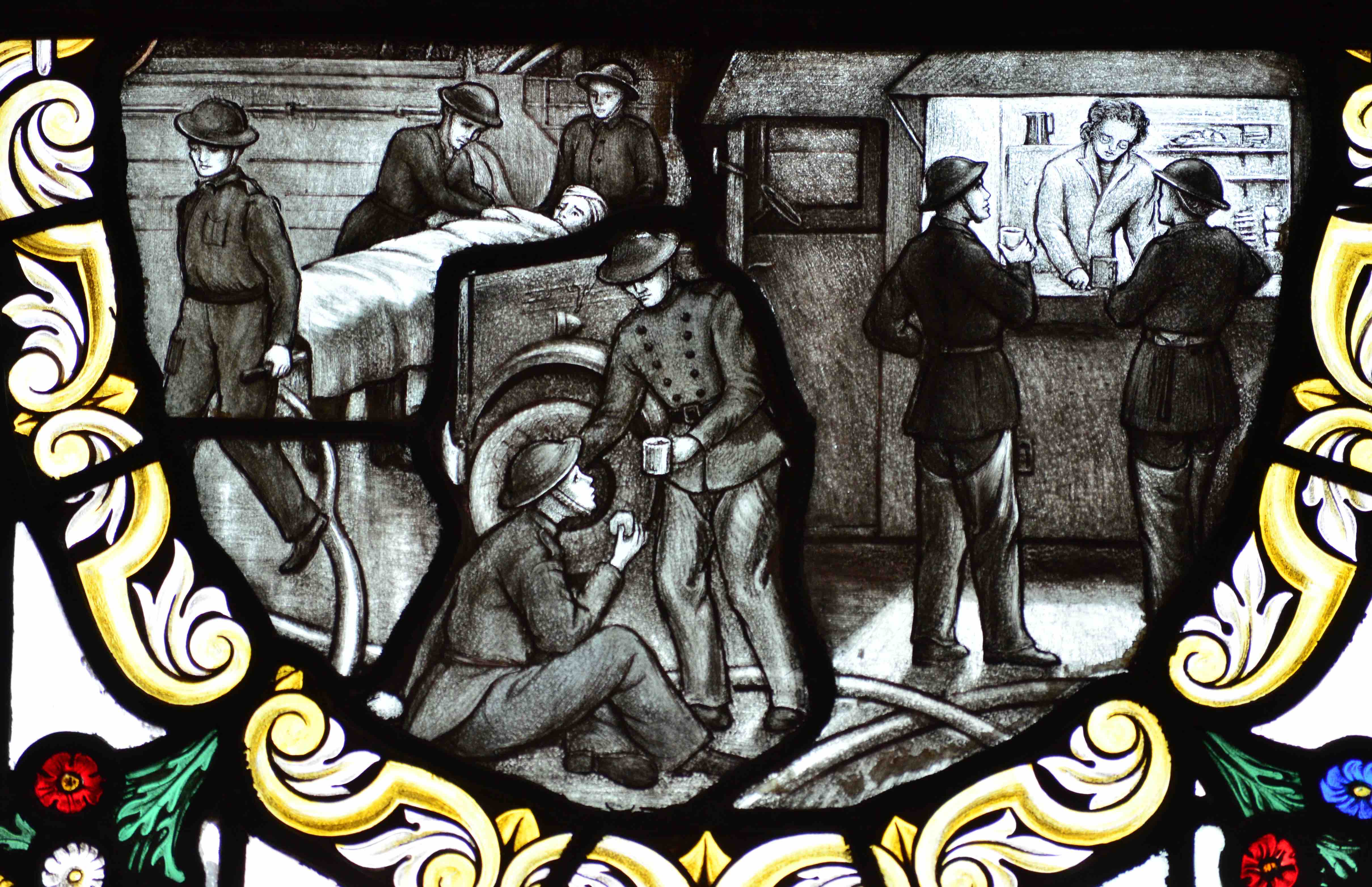

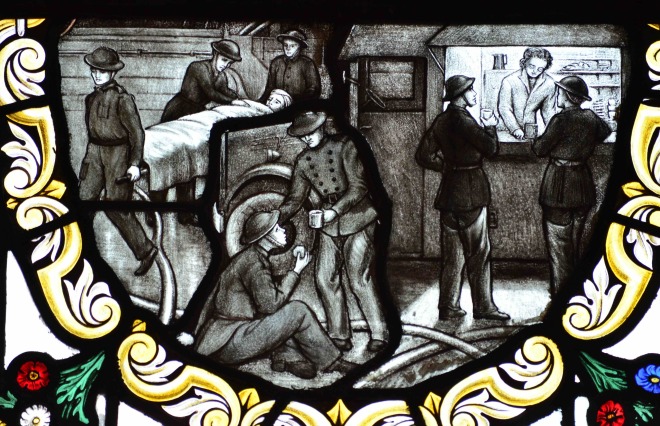

The Parable of the Lost Coin is at St Lawrence, Sandhurst, Glouc. It was designed by Harry Stammers in 1949. Jane Brocket has written eloquently on her blog here about his work opening up the whole world of stained glass for her. When she came across the windows by him in the Lucy Chapel at St Mary Redcliffe in Bristol. ‘I was amazed. I’d never seen ordinary people in ordinary, contemporary clothes. Headscarves! Handbags! Court shoes! Aprons! On women who weren’t saints or queens, but who probably scrubbed doorsteps and cleaned out stoves and swept floors, brought up children, and took them to Sunday school. Women who had a shampoo-and-set once a week, went shopping with baskets over their arms and wore sensible coats in winter. The kind of women I saw and knew when I was growing up: mothers, workers, wives, daughters. And here they were. Not beautified, idealised or objectified, but depicted with clarity and simplicity and dignity… I’d always assumed stained glass wasn’t my sort of thing, yet I found myself completely enthralled by a mix of post-war Social Realism, abstraction, woodcut linearity, book illustration, poster design, plus glorious colour, superb handling of huge windows, and masterly manipulation of light. Harry Stammers (1902-1969) was my introduction to stained glass, my way into looking at and appreciating an art that is so often excluded from art books. That is the story of my stained glass epiphany, my conversion.’