A beautiful frieze in Moscow, presumably of Russian workers, it’s quite hard to tell, but the quality of the carving is remarkable – and there are many carvings like this all over the city.

A beautiful frieze in Moscow, presumably of Russian workers, it’s quite hard to tell, but the quality of the carving is remarkable – and there are many carvings like this all over the city.

On the same street as the Chekhov statue (cf. the Post last week) there is a branch of Le Pain Quotidian. For the European, Russia is such an extraordinary mixture of the familiar and the completely different.

Some Russian holiday snaps this week on the Post, but only five, which is better than the 635 or whatever that Pat and Tony on The Archers are inflicting on their friends. This is the kind of mural/sculpture that one sees a lot of; yet it’s quite hard to know how to react because the non-Russian has such conflicted feelings about it. On the other hand many of us are not so keen on the statues of generals on horseback which can be seen all over central London, although we pass them by without a second glance.

The Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow has the famous Portrait of an Unknown Woman 1883 by Ivan Kramskoy, which has been used as the cover for several editions of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina 1873-7. Here is a good piece by James Meek replying to the question: ‘What is it about Anna Karenina that gives it special status among the great novels?’

This statue of Chekhov is in Moscow on Kamergersky Pereulok, a pedestrian street near the Bolshoi. Chekhov wrote stunningly well about women. And most unusually. In a short story called ‘A Woman’s Kingdom‘ he describes a woman who has inherited a factory and responsibilities but wishes she hadn’t: ‘She thought with vexation that other girls of her age — she was in her twenty-sixth year — were now busy looking after their households, were weary and would sleep sound, and would wake up tomorrow morning in holiday mood; many of them had long been married and had children… she longed to wash, to iron, to run to the shop and the tavern as she used to do every day when she lived with her mother. She ought to have been a work-girl and not the factory owner!’

Persephone Books publishes one of the great Russian women writers – Eugenia Ginzburg. In a blog last August Esther Harper wrote about Into the Whirlwind: ‘The essence of this book is one innocent woman’s story of life, freedom and affluence being stripped away from her, and replaced with a life where mere survival is the focus – a life where every scrap of bread, every half-cup of dirty water and every fishbone sewing needle is a means of simply carrying on. It is a story of what is left when all she knows and loves is snatched away – what of her remains, what she turns to, and who she becomes.’ We are showing the film (which stars Emily Watson) next week.

Nadezhda Mandelstam (1899-1980) married the poet Osip Mandelstam in 1922. ‘After his arrest and death in 1938 she saved his poetry by committing it all to memory, and saved herself by fleeing to the remote eastern regions of Russia. She was allowed to return to Moscow in 1956 and fought to get Osip’s work back into print. In the late 1960’s Mandelstam had her two monumental volumes of memoirs (unpublishable in the USSR) smuggled into the west, where they appeared as Hope Against Hope (1970) and Hope Abandoned (1974); together they offer a unique look at life among the Russian intelligentsia under Stalin and beyond. In her last years she was revered by Russian writers, who made endless pilgrimages to her one-room Moscow apartment.’ This photograph is here. Clive James wrote eloquently about Nadezhda Mandelstam here (‘Hope Against Hope puts her at the centre of the liberal resistance under the Soviet Union and indeed at the centre of the whole of 20th-century literary and political history’) as he did about Anna Akhmatova here.

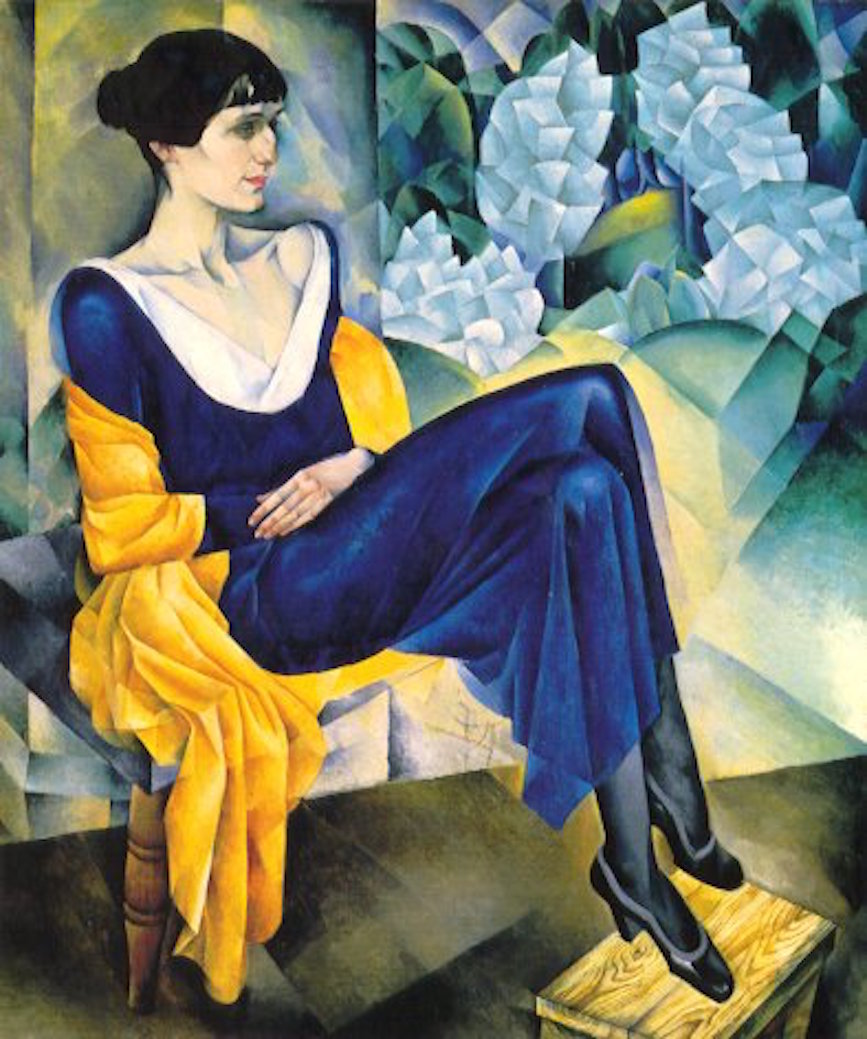

One third of the Persephone Books office has been in St Petersburg and then Moscow for the last ten days so this week on the Post – Russian women writers or (since there are alas not so many of these) writers very much associated with women. First, irresistibly, the famous 1914 painting of Anna Akhmatova by Altman in the Hermitage. We also visited the flat where Akhmatova lived.

Golden seems to have remained living in London all her life, always being most interested in the pockets of the city where people worked; friends remember her loving to watch the people on the Thames from to top floor of her house in Southwark. This is the 1951 edition of her book Old Bankside which tells the stories of the famous Londoners who congregated by the river (a sort of precursor to Gillian Tindall’s The House by the Thames).

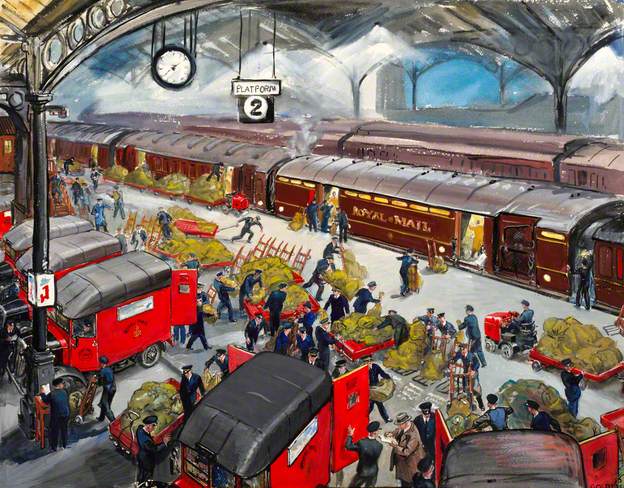

Euston Station: Loading the Travelling Post Office (1948) is at The British Postal Museum and Archive (the museum store in Essex has this exact model of bright scarlet postal van on display).