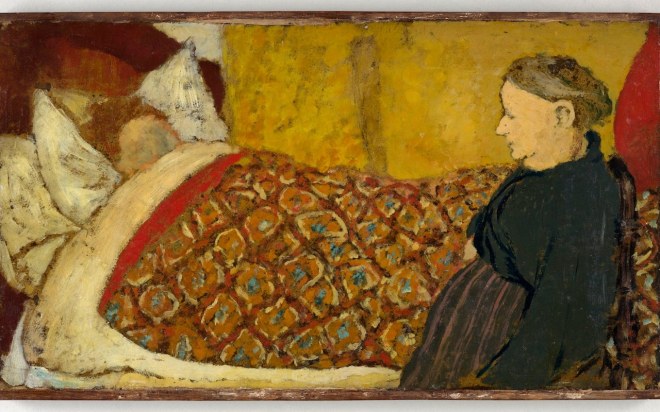

‘Early critics noticed the intimate, mysterious nature of Vuillard’s everyday domestic scenes, which have a subtly theatrical quality (he was a keen devotee of Ibsen and Strindberg, and designed theatrical costumes and scenery). As one writer put it in the 1890s, his pictures speak, as it were, “in a low tone, suitable to confidences”. Yet, for all their quiet modesty, and debt to traditional domestic interiors by Vermeer, Vuillard’s “intimiste” paintings (as they are known) have a surprisingly radical quality. In part, this is due to the way he manipulated paint: frequently, his brushwork appears crude and unresolved. He also painted on cheap, unconventional surfaces, such as cardboard. His subject matter was avant-garde, since, in an unexpected way, it dramatised modern life. Before Vuillard, few artists depicted bourgeois women performing housework – that was done by servants. Moreover, by painting his mother toiling in her dressmaking workshop, alongside the seamstresses she employed, Vuillard was shining a light upon something hitherto undocumented: the thousands of women in Paris’s garment industry who worked from home. The Lullaby (1894), which Vuillard kept until his death – after which it was acquired by Picasso – provides a good example: Madame Vuillard, seen in profile, watches over the artist’s sister, Marie, her body hidden beneath a vibrant diamond-patterned bedspread, her face a milky blur. At the time, Marie was pregnant, and the painting documents a serious illness that sadly resulted in a stillbirth.’