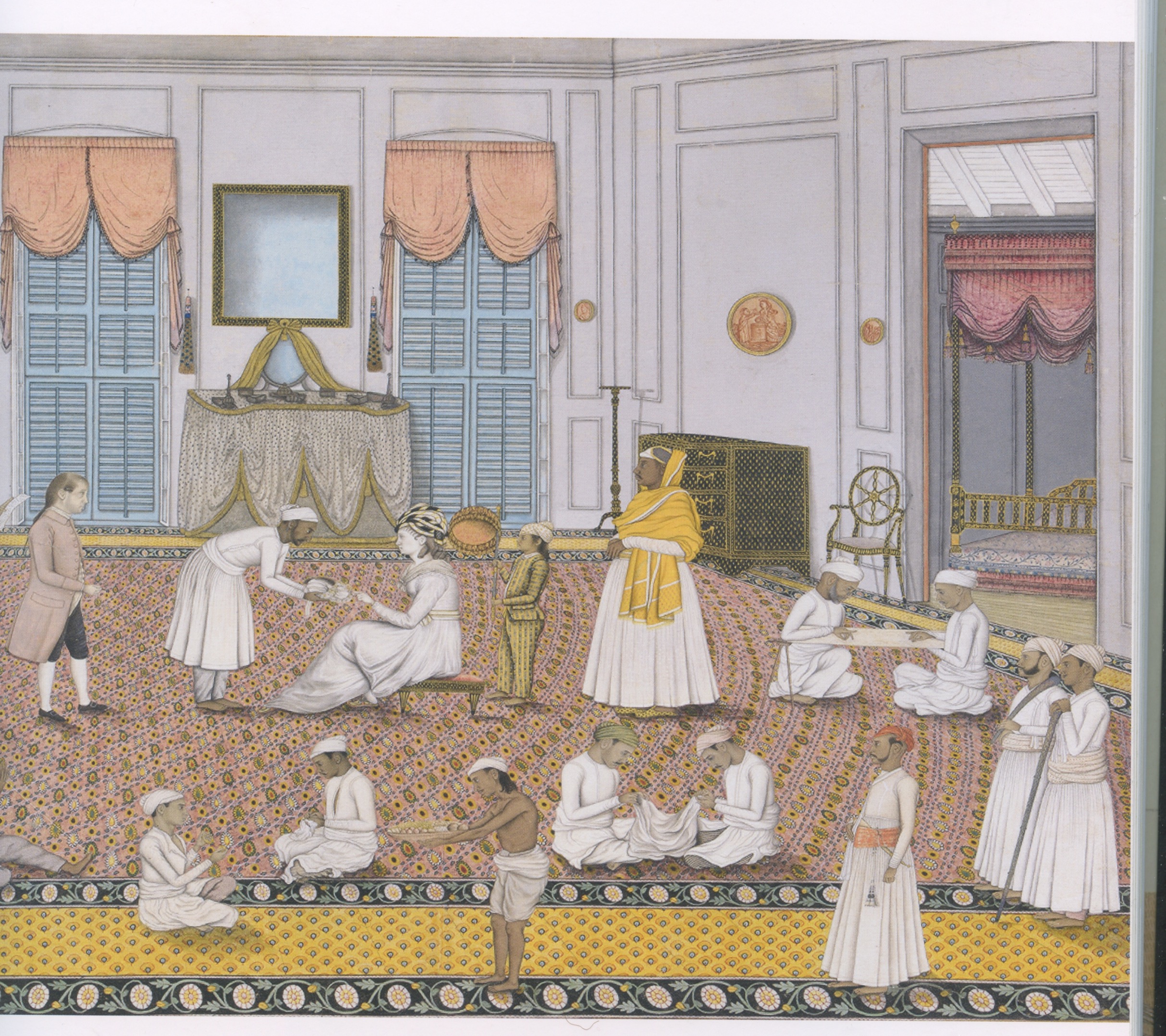

‘The British didn’t stop at birds and plants.’ wrote Rachel Spence in the Financial Times. ‘They also commissioned images of architecture, festivals, dancers, soldiers, craftspeople, villagers, princes and courtiers. Yet it is difficult to regard these drawings — which encompass images of dancing girls, soldiers, princes, village elders and horse merchants — without unease. Pinioned against those empty backgrounds just as the Indian birds were, many of the figures have a lonely, vulnerable aspect that reveals the colonising impulse behind the European urge to chronicle, taxonomise and demystify their new territory. Nevertheless, Forgotten Masters has much to tell us. Since the 1950s, this genre of art has generally been known as Company School painting. Disregarded by historians of Indian art due to its Eurocentric characteristics and the names of its artists being either unknown or neglected, its topography has remained unmapped. But it is worth exploring for, beyond the art itself, the mechanisms by which it was commissioned reveal fascinating insights into the reality of relations between British and Indian people in pre-imperial India. Some of the most revealing portraits are of European patrons. Lady Impey, for example, is captured by a painter thought to be Shaikh Zain Ud-Din in the act of “Supervising her Household in Calcutta”. Wearing a turban, as her servant presents another turban for her inspection, she sits on a footstool under the breeze of a fan held by a page boy. Surrounded by Indian servants, who are arranged in various tasks with stylised precision, and one European steward, Lady Impey appears at once in control yet out of place. Was the painter conscious that he was failing to flatter?’