A friend wrote to us about The Far Cry and Patience (we love it when people enjoy our books and take the trouble to write about them with such intelligence and perception: this, we feel, is why we do our job): ‘We have both just eaten up The Far Cry. Always the books we read aloud before going to bed are a huge treat, because time together alone now is so rare and delightful, but this book – well, it’s just as Susan Hill says: it springs off the page with all promise fully realised. How could she have observed with such depth and humanity these very complex relationships? It would have been a beautiful observation of an awkward girl’s coming of age if it had been just that, but the very complex relationship she had with her father (unusual to have a negative one portrayed, isn’t it?) and the strange, tragic couple, and the prickliness of the girl with the young employee, and Miss Spooner (who seems to be exactly as one of Iris Murdoch’s characters who embody goodness even as they slip self-effacingly out of the frame) and with India itself… all these are are described with the subtlety you couldn’t expect from anyone that age. And then those set pieces – the swimmers breaking up the water, or the arrival in Calcutta – seemed a sort of verbal equivalent to early 20th century paintings of humanity pushed into near-abstraction.

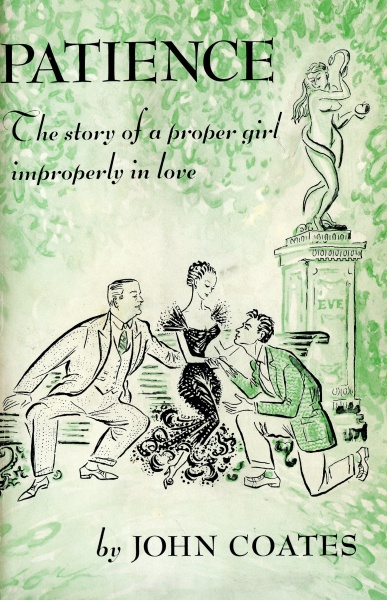

‘Of course, Patience is heavenly. What a salutary warning to all bridegrooms, and men in general! And very apposite to the Me Too conversation. Interesting that John Coates was also a playwright: it occurred to me as I read it that it was really an interwar bedroom farce – perhaps with a little more of the Ivor Novello romance than Coward’s satire. And the interesting thing is that while it’s about the joy of mutual sexual desire, it’s surely much more about the joy of faith-truth-love-desire and the absurdity of blind selfishness and Edward’s sex-as-physical-satisfaction? After all, Coates carefully protects Patience’s moral and actual and even ecclesiastical integrity all along, however much she believes/fears that it’s only the illicitness that makes love of Philip a continuation of love of her beloved people/Heaven. It’s almost a relief when she sleeps with him before they are married, so that that Catholicism’s dogma can be set against actual pastoral practice, and Patience shows herself to be human AND capable of giving and receiving forgiveness, which is what Christianity is all about, whatever the Churches have led people to believe. (Though even here, Coates is having his cake and eating it, so to speak, because by then, we are utterly convinced of Patience’s blamelessness and the reality of the marriage to Philip. But then isn’t that always the way in most plays, books and films? We may be allowed to watch a hero or heroine sail perilously into Sin because therein is the drama, but there’s always a very careful policy that we must feel they are blameless in the absolute moral sense, and even often in a worldly sense, which only reinforces the general consensus that goodness, fidelity, integrity is essential to human life and love.)’

‘I think John Coates handles all that business amazingly skilfully – the way in which Patience can articulate an artless critique of Catholic casuistry, and take simultaneous advantage of it, and also (sincerely) keep thanking God for the wisdom of its teaching, which somehow rewards the innocent in the end. And I note that it’s Father Thomas who is given the role of helping Patience into married bliss. Whereas I’m given quite a jolt at the silliness of previous legal divorce laws, and the circumlocutions required to obtain them. (I’m not au fait with what ‘asking for discretion’ means, so I had to look it up, and found a very interesting argument for abolishing ‘this Victorian instrument of torture’ in an article by N. Simon Tessy in ‘The Modern Law Review’ in 1958.) An interesting side issue arising from this is his use of the masculine throughout in referring to the petitioner, whereas I’d have thought it would have made more sense to use the ‘she’, given that most petitioners for divorce were women, were they not? And I think all the cases he cites have women as petitioners. Is this just the convention in legal writing of the time? Was it difficult for him to envisage or write about women disclosing sexual misconduct in the way he must in order to make his case?’

Ali Smith and Nicola Sturgeon appeared together at the Edinburgh Festival – it must have been fascinating. Ali Smith said: ‘We are living in a culture that insists on lying as its delivery of how we are living. It insists on telling us information about which we are left wondering whether it is true or not … Fiction and lies are the opposite of each other. Lies go out of the way to distort and turn you away from the truth. But fiction is one of our ways of telling the truth.’

There is a silent film festival at Pordenone from 6th-13th October. This year they are showing the 1925 silent film of The Home-Maker.

The National Portrait Gallery has bought a portrait of Dylan Thomas by Augustus John.

Jane Brocket alerted us to this in her (newly restarted and intensely readable) blog Yarnstorm here. Jane is in fact joining a small team from Persephone Books at the Women’s Equality Party conference in Kettering next weekend: she will be helping us ‘man’ or, obviously, ‘woman’ our stall on Saturday and Sunday.

Nicola Beauman

59 Lambs Conduit Street