This Letter is being written on our annual Open Day when all books are gift-wrapped free of charge. And it has been very, very busy – books have been bought and the Konditor and Cook mince pies and the mulled wine have been consumed all day.

In honour of Christmas this letter is going to be a politics-free zone! Of course the definition of political varies from person to person, for example does Samantha Ellis’s brilliant How to Date a Feminist count as a political play? It is full of trenchant (and hilarious) aperçus which some might define as political.

And what about Beth Gutcheon’s Still Missing (the subject of this month’s Persephone Forum)? Is the question of whether or not one’s children can walk to school on their own a political issue? Well, by the standards of 2016 neither are anything to do with politics

So this week on the Post we had the most unpolitical thing one can think of – teapots: although it has to be admitted that the piece in the recent Biannually (taken from Alan Macfarlane’s excellent book about tea) does nevertheless touch on the question of politics (it was only with the invention of tea as a ‘respectable’ drink that women could gather together in groups without eyebrows being raised).

Twenty-five Persephone readers gathered in a group on November 16th when Harriet Evans and Lydia Fellgett were (very) informally in conversation at a Persephone lunch in the shop about Dorothy Whipple.

Here are some equally informal notes about what Harrie and Lydia said: Dorothy Whipple is, they agreed, a Condition of England writer: although not a Victorian novelist her books are in the tradition of novels like Mary Barton, Hard Times and Sybil. She has a small canvas but writes long books. She is a storyteller through and through and is superb at telling a story (although her plots are not complicated and for most of her novels can be summarised in a sentence). As Harrie Evans pointed out, she doesn’t indulge in flashbook (there are no sentences of the ‘that summer everything changed’ kind). What happens, happens in order: the narrative is the story. Dorothy Whipple doesn’t mess you about. Her prose is generous spirited (in the way that Angela Thirkell is mean spirited). She was a very sensitive person with one layer of skin missing. Random Commentary is so readable and so funny. She should be compared to Jane Austen, Mrs Gaskell, Trollope and Alan Bennett, not to Elizabeth Bowen, Rebecca West, Virginia Woolf and Elizabeth Taylor (although the latter obviously read her, cf. the recent Biannually). As for character – she certainly gets people. She is very much of the historical moment at which she was writing: ’the moment of cultural production’ ie. no book is written in isolation.’ She is middle class/middlebrow/middle England – and yet she was much, much more than that. Who was her rival? Du Maurier, Waugh, Priestley, Maugham. She became friends with Wells and Priestley but was not ‘well connected’. Nowadays you have to be a brand. The Americans rejected The Priory. In a smaller pool the recognition is greater. She doesn’t do houses, she unpacks a family (though Harriet thinks that the end of Because of the Lockwoods displays one of her rare weak moments). Her hard work makes her books a pleasure for us to read: she is a very generous writer. But she is not interested in playing around with style – she is no TS Eliot, no Joyce. She is very funny; takes great pleasure in unfolding of what happens to these people; so comforting. She has a very strong moral focus and a very nuanced understanding of social class. But she’s not snobby: she lets you know that the Lockwoods weren’t classy, without being judgmental. For her, domesticity means making the preserves, polishing, paying attention to the details, being caring and careful. Making jam – the domestic – was a crucial part of her and her contemporaries’ life. She didn’t use the word feminist. Her heroines notice things. Would she have been a novelist if she had had children? She is so good on children, so good on men. Her dialogue is superb – she would have been a brilliant playwright. She is good at big novels and short stories. Her northern roots. Like other Northern writers she is unpretentious, direct and economical – only the snobby people are pretentious. She’s about trying to be a good person: Ellen in Someone at a Distance is virtuous. In conclusion: Dorothy Whipple is very true to lots of people’s lives.

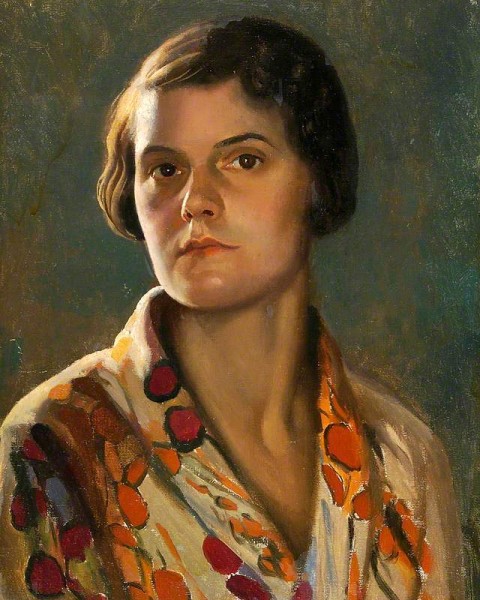

Finally: the picture on this page is not actually of Dorothy Whipple herself. It is a 1932 self portrait by Effie Spring-Smith (1907-74). We have used it to illustrate The Closed Door and Other Stories – because this is exactly how we imagine the blessed Dorothy’s heroines might have looked.

Nicola Beauman

59 Lamb’s Conduit Street