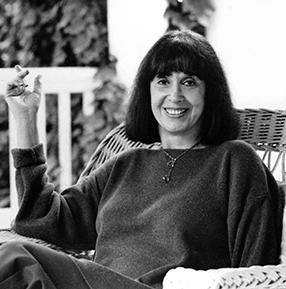

Judith Viorst was born in 1931 in New Jersey. She is eighty now and in a very brief resumé of her life showing on her publisher’s website, she charts her writing career from the age of 7, when she wrote her ‘Ode to my Dead Parents’, to her early thirties when she got married and decided to write ‘short funny poems, instead of long miserable ones’. They are funny and touching because, although they are very American, quite Jewish, and very much of the sixties, the situations, the relationships and the emotions that they describe are unchanging.

The names are from the sixties, the food is date stamped 1965, the clothes are vintage: how long since anyone wore a chiffon peignoir, or a green Dacron dry-mopping outfit, or rollers in bed. The setting may be half a century ago and an ocean away, but the poems delight because the subject matter remains central to women’s lives: family, love, marriage, children, ageing, envy, other women and the ‘other woman’, anxieties about fitting in, about who we want to be, about who we might have been. Any young mother, any newly-wed (or newly cohabiting in 21st century parlance), any woman in her thirties, will surely recognise aspects of themselves in It’s Hard. And any woman no longer in her thirties will recognise that as the decade, when she was forced to realise that the first flush of youth had past, that middle age was closer than teen age.

Viorst herself said ‘I probably have cried over everything that I wound up writing funny poems about.’ What makes the poems work for the reader is that we too have cried over the things that she writes about, and, if we are lucky, we may have been able, later, quite a lot later, to laugh about them. Then ‘after crying, whining, moaning ‘Why me!’ and, whenever possible, blaming my husband’, she writes, ‘I have managed to find some humour in the ‘tragedies’ and ‘aggravation’ of life.’ If we haven’t yet found the humour in our own disappointments and failures, she invites us nonetheless to see the funny side of hers.

Viorst has a brilliant ear for dialogue, catching the voices (and the clichés) of a whole cast of family and friends: the aunts and uncles who were grateful her prospective husband

…came from a nice family in New Jersey even though he

wore sunglasses in the living room which is usually a sign

of depravity.

His aunts and his uncles were grateful

I came from a nice family in New Jersey even though I lived

in Greenwich Village which is usually a sign of depravity

also.

her mother, who wistfully talks of Freddie, the New Jersey bachelor, with waves in his hair, who

… has cashmere sweaters,

A Danish-modern apartment,

A retirement plan,

And what is known in New Jersey as

Sound investments….

And whenever my husband is showing

What is known in New Jersey as no respect

For my mother,

She tells about Freddie the bachelor,

Who never talks back and is such

A good catch.

her mother-in-law, who ‘Comes to visit with her own apron’ and whose son

She thinks she should mention,

Looks thin as a rail …

‘The First Full-fledged Family Reunion’, is an audible group portrait, including

1 cousin you wouldn’t believe it to look at him only likes

fellows

1 nephew involved with a person of a different racial

persuasion which his parents are taking very well

…..

1 cousin who has made such a name for himself he was

almost Barbara Streisand’s obstetrician

…..

2 aunts who go to the same butcher as Philip Roth’s mother

And me wanting approval from all of them.

We smile because we recognise those flawed characters and we recognise in ourselves that irrational but all too real need for the approval of people we don’t even admire.

Social approval is just as elusive. Fitting in is hard to do, whether it be in ‘swinging London’

… standing on the King’s Road

With wet feet,

Indigestion,

The wrong hemline

in sophisticated Deauville where

… even if we had arrived

With an Alfa Romeo,

A yacht,

His and her dinner clothes by Pierre Cardin,

And a handwritten introduction from Françoise Sagan,

They would still know

We did not belong

In Deauville

or at home in Washington DC, where surrounded by ‘the fun couples/Who own works of art’, ‘the boycott-the-supermarket people’, ‘the social leaders’ and ‘the self improvers’:

…we can’t decide

Who we want them to think

We are.

When she does feel herself fitting in at ‘The cocktail party’, where

The hostess is passing the eggs with the mayonnaise-curry

and

The husband is being risqué with a blonde in the foyer, and

The mothers are finishing ear aches and starting on day

Camps …

she ruefully admits

I’m not as out of place

As I wish I were.

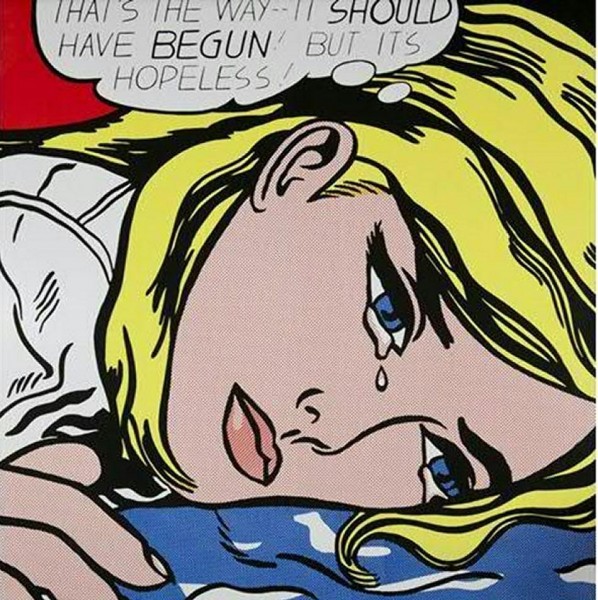

Some of her best poems are about marriage, its pains and pleasures. You can’t live the dream, she seems to be saying, and the sooner you learn that lesson the better for you. No-one says it will be easy. When expectation meets reality, it is expectation that must give way, and it is painful. But in retrospect it can be funny, especially if you can share the joke.

Asked about the key to a long-lasting marriage (Judith Viorst has been married for over 50 years) she replies: ‘dumb luck plus a huge amount of hard work and a willingness to laugh’. The hard work begins right after the honeymoon, when he leaves for work, ‘whistling something obvious from La Bohème’ and she finds herself dry-mopping the floor, wondering why she’s not dancing in the dark or rejecting princes. Already the two of them ‘find that dining by candlelight makes us squint’. . The truth is she never knew a prince (fantasising about the past is just as dangerous as fantasising about the future) and it’s time to get on with living the reality: ‘…they call this getting to know each other.’

How accurately she pinpoints the niggling details, the unreasonable expectations, the irritating habits that have to be addressed or accepted if marriage is to survive the honeymoon,

If I quit hoping he’ll show up with flowers, and

He quits hoping I’ll squeeze him an orange, and

I quit shaving my legs with his razor, and

He quits wiping his feet with my face towel, and

We avoid discussions like

Is he really smarter than I am, or simply more glib,

Maybe we’ll make it.

There are times when it seems that ‘The Other Woman’ has the better deal. She ‘spends her money on fine furs’ and is a ‘good sport’ when it comes to ‘things like flat tires and no hot water’, ‘Because it easier to be a good sport/ When you’re not married’. How well we recognise that other woman who, unlike us, ‘never smells of Ajax or Spaghetti O’, and don’t we just hate her. But tallying up the losses and the gains, it was worth giving up the promising career ‘as assistant to the editorial assistant to the editor’, or ‘sitting on a blanket in Nantucket’, or

…an affair with a marvellous man

Who would leave his wife immediately except that she would

slash her wrists and the children would cry.

It was worth it

Because, as someone once put it,

Married is better.

And then there are the children. It’s hard to be hip over thirty, because ‘everyone else is nineteen’, and

The Love-Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,

Which we learned line by line long ago,/

Doesn’t swing we are told, on East Tenth Street,

Where all the perfect girls are switched-on or tuned-in or miscegenated…

But what really gets in the way of being hip is ‘Serving Crispy Critters to grouchy three-year olds’ and having ‘to show up for the car pool.’ From the moment of their arrival children make their mark, literally: baby food on the smart Spanish rug, strained banana in our hair, baby dribble on the antique satin spread. The beautiful life and parenting don’t belong together. Another dream bubble bursts. ‘It is often said/ That motherhood is very maturing’. Those who have ‘enjoyed’ motherhood would agree wryly. And no sooner has the rug been dry-cleaned than the harassed mother pictures the children growing up, sniffing glue, smoking pot and ‘Slipping LSD into their cream of wheat’. It’s never too early to start worrying.

It’s Hard to be Hip Over Thirty – the title says it all, almost all. What is missing from the title, and from the title poem, is the stoicism, the fortitude, the acceptance of life as it is, or rather as it turns out to be.

Judith Viorst’s most successful children’s book, Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, ends, not happily, but realistically: bad days don’t turn out to be good days after all. The lesson is that those days happen, (even in Australia – Alexander had dreamt that it might be possible to escape them in Australia). Small boys learn that no good days happen to other small boys, which is a comfort. And they learn that good days can follow bad days, and that there is something funny about the bad day, although not at the time. Their mothers, and grandmothers, learn from her poetry that their no good very bad days are not unique to them, that the perfect life, like the perfect husband or the perfect child (or being the perfect wife and mother) is a chimera, and the best we can do is to laugh about it.

Questions

Can we learn life-lessons from poetry?

How easy is it for a British reader to identify with Judith Viorst’s poetry?

It’s Hard to be Hip was first published in 1968. Forty years on, how much has changed?

One reply on “Persephone Book No.12: It’s Hard to Be Hip Over Thirty by Judith Viorst”

You ask if we think Judith Viorst is relevant to today, and whether an English reader would be able to appreciate her poems. I think she shows that, whilst her work is very much of its own time and place (as shown by her references to invading Indochina in ‘Sandra Shapiro is Such a Good Mother’), it is not tied down to ’60s/’70s America. Indeed, in poems such as ‘Sex Isn’t Sexy Anymore’ I think she looks forward to the work of our own Victoria Wood, Pam Ayres, and Jenny Joseph. At the same time, her choice of subject (the limited choices offered to women) shows that in her poems such as ‘Money’ and ‘The Writers’, she is universal and a throwback to Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’ and Simone de Beauvoir’s ‘The Second Sex’, whilst her use of brand names throughout is an echo of writers such as Ian Fleming and John Betjeman.

Although I like her work, many of her poems leave me wishing that she’d worked as hard on her rhymes as she did on her rhythms. Viorst’s choice of words at line endings often left me hanging in expectation of cleverly manipulated word echoes that didn’t appear, such as in ‘The Lady Next Door’. Rhythm is obviously more important to her than rhyme but the reader shouldn’t feel cheated – and the poem ‘Decay’ is weak in both areas. However, ‘The Writers’ is brilliantly strong in rhyme, rhythm and philosophy. I like her.