Harriet was published in 1934, when Elizabeth Jenkins was twenty-nine. It was her second novel, and a considerable success, beating A Handful of Dust to win the Prix Femina Vie Heureuse, but she would later be reluctant to have it reprinted. ‘The horror of the story weighed on my mind and became more acutely painful as time went on,’ she wrote. She could not, she said, have written it after the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps became known.

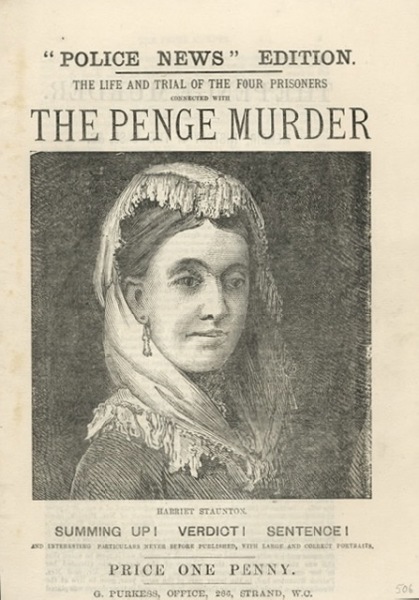

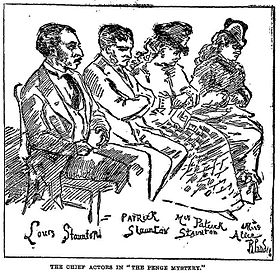

Closely based on the court records of a trial of 1877, popularly known at the time as the Penge Murder, a crime in the author’s words ‘involving almost unbelievable callousness and cruelty’, it is a grim story of greed, selfishness and lust, in an age of damaging social, economic and sexual inequality. The trial was widely covered in lurid detail in the press. Fashionably dressed women crowded the public gallery throughout, apparently drinking champagne and peering through opera glasses at the four miserable characters in the dock. ‘What hearts of stone these women must have,’ commented one journalist, conveniently ignoring the keen interest taken by the large number of men in the courtroom.

The jury was asked to decide if Harriet Staunton, a woman of ‘weak intellect’ had met her death ‘through the culpable misconduct of the prisoners, or any of them, and if so, whether that misconduct amount to murder or manslaughter’ – had she been left without food with design of causing her death (murder) or cruel negligence (manslaughter). No physical detail was spared in the course of the trial – the layout of the house, furniture, linen (or lack of in the victim’s case), clothes (lack of), meals (lack of), fires (lack of), bruises (no lack of). Biographical details are limited and it was not the job of the court to suggest any psychological explanation.

Who were the four people in the dock, how did they get there, what sort of lives had they led, how were they linked, how did a middle class woman of means, albeit of low intelligence, become a victim? Was there a point at which the downward trajectory of her life might have been reversed? The bejewelled ladies in the gallery may have speculated over their champagne. In Harriet Elizabeth Jenkins takes the bare facts and gives them flesh. The novelist makes the unbelievable believable. The individuals in the dock, and those outside it, are given histories, vulnerabilities, motives. Without pretending to defend those who patently don’t deserve it, she shows how their lives, and their actions, have to varying degrees been determined by class, money and gender; how heredity and accidents of birth, even family position, have influenced looks, character and intellectual capacity, and how chance can alter everything.

With better luck, Harriet Owen (only the surnames are changed), damaged at birth, ‘a natural’ in Victorian country parlance, might have been protected by class and money, but both work against her. Sheltered for thirty years in a prosperous home, her limited intellect stimulated by her mother, her future assured by a generous legacy, she could, in spite of her slightly slurred speech, a tendency to laugh inappropriately, and a disabling lack of empathy, have lived a good enough life. But money, even in such an unattractive woman, would prove a draw to an unscrupulous, not over fastidious, fortune hunter, and her confidence, carefully nurtured by her rich mother, would be taken for complacency by strangers, and as condescension by her poor relations.

Harriet has no understanding of the feelings of others, and barely more understanding of her own. Even her mother is borne down by her ‘horrid uncouthness’, and seeks regular respite in sending her away to stay with members of her family, fortunately both numerous and impoverished. The stays are long and the cousins are well reimbursed. Jane Ogilvy is not a bad mother but does not want to trouble her husband overmuch with his step-daughter’s problems (Harriet’s father is long dead); she is no longer young, she is weary, and we can assume that the arrangement has worked well enough to date. No blame there – but the question hangs in the air. Had she kept Harriet at home and not sent her to the Hoppner cousins in Clapham, the fateful encounter with Lewis Oman (Louis Staunton), a man driven by greed lust and a deranged sense of entitlement, would not have occurred.

How different Harriet’s life would have been had Mrs Hoppner not needed the extra income, had her selfish and indulged younger daughter not expected to dress above her station, had her older daughter, Elizabeth, not needed temporary accommodation with her penniless artist husband Patrick Oman and their children, had his brother, Lewis, not happened to visit. She would have lived out her life in a comfortable upper middle class home, enjoying nice cakes and shopping at ‘the big expensive shop in Regent Street’. She had never expected, nor been expected, to marry. Her downfall is not the result of passionate rebellion, or of any misdemeanour: no adulterous liaison, no illegitimate child. Harriet is no stereotypical Victorian tragic heroine. She is a victim of circumstance, a social misfit, not so much cast out as cut adrift.

We are often asked what links the titles in the Persephone collection and one answer is that they are ‘domestic’. They are broadly speaking about women’s lives, the ordinary rather than the extraordinary, and, even more broadly speaking, about the social and historical factors that play an important part in determining the course of those lives. It is also true that most are, to use a rather over-used adjective, redemptive. Bad things happen to good people, but somewhere there is light ahead. In her afterword to Dorothy Whipple’s They Knew Mr. Knight, Terence Handley Macmath, uses the word ‘salvation’, which can come from outside, a chance encounter, a stroke of luck (Dorothy Whipple and Terence Macmath take a more religious view), or from a character’s unsuspected, and previously untested, inner strength.

Harriet could be said to depict the very antithesis of what we think of as ‘the Persephone novel’. Many, if not all, of our Victorian heroines suffer from a lack of money or the lack of a husband or both. Harriet has money; she does not need a husband; she is not expected to marry: indeed her mother actively tries to prevent her from marrying. Her limited intelligence precludes conventional domesticity, her parenting skills are tragically inadequate. Though the details, many taken directly from the court records, are brilliantly reimagined by Elizabeth Jenkins, the everyday lives of those with whom Harriet is forced to live are grim, and barely ordinary. And there is no salvation.

In her memoirs, A View From Downshire Hill, compiled when she was already in her nineties, Elizabeth Jenkins was fiercely critical of her prize-winning novel: ‘I gave the sordid tale an interest which I now see it never had.’ She was far too self-deprecating, and mistaken in not wanting it republished. It is, in the words of the TLS reviewer, ‘a terrible but enthralling tale.’ The other feature of Persephone Books that we never fail to mention is that they are ‘page-turners’. Harriet is a page-turner.