At the beginning of this month the Prime Minister announced that, in order to commemorate the centenary of British women’s enfranchisement, a statue of the pioneer of women’s suffrage, Millicent Fawcett, was to be erected next year in Parliament Square. Not, one might say, before time.

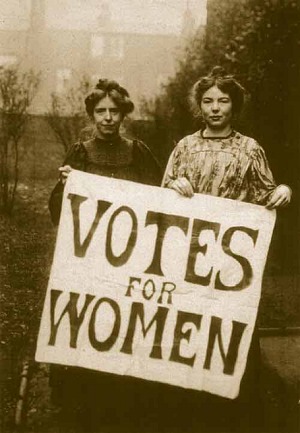

In October 1905 two women interrupted a Liberal rally: they wanted to hear Winston Churchill and Sir Edward Grey’s view on women’s suffrage. Getting no answer from the politicians, the women raised the banner which they had been concealing, demanding ‘Votes for Women’. The women were ejected from the meeting, charged with causing an obstruction and assaulting a policeman, and arrested. Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney refused to pay the fine imposed, choosing instead to go to prison. Christabel Pankhurst needs no introduction; Annie Kenney was a mill-worker from Yorkshire, one of the 37 000 Northern textile workers to sign the petition making the same demand, delivered to Parliament three years earlier.

Before the 1905 protest, a Private Members’ Bill to enfranchise women had been squeezed out of parliamentary time by one requiring carts using public roads to be fitted with lights, but much had improved for some women in the latter part of the nineteenth century. The Married Women’s Property Act had been passed in 1882, the Guardianship of Infants Act in 1886: this increased, but far from ensured, a mother’s custody rights (mothers did not get full equal custody rights with fathers until 1973). The 1857 Matrimonial Causes Act had made divorce possible for ordinary people, but it was expensive, and a wife was required to prove cruelty, rape or incest in addition to adultery. Although they would not be paid the same as men nor enjoy the same employment rights, some professions were open to women. None of these changes, although loudly trumpeted by anti-suffragists, meant a great deal to working-class women, who had no property, could not afford to leave a brutal husband nor fight his abduction of their children, who had little or no schooling after the age of ten, and who were still many decades away from equal pay with men. Only the vote would give women power over political decision making, only the vote would bring improved working conditions, support family life and, the Suffragists believed, change the sexual double standard.

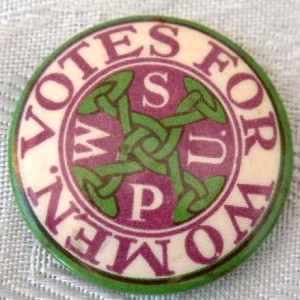

Annie Kenney was twenty-six in 1905 and had only recently joined the Women’s Social and Political Union, the activist breakaway movement led by Christabel and her mother, Emmeline, which had split from Millicent Fawcett’s non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies in 1903. The only working-class woman to rise to the senior hierarchy of the essentially middle-class WSPU, she would be imprisoned a dozen more times and subjected on several occasion to the vile and violent practice of force-feeding.

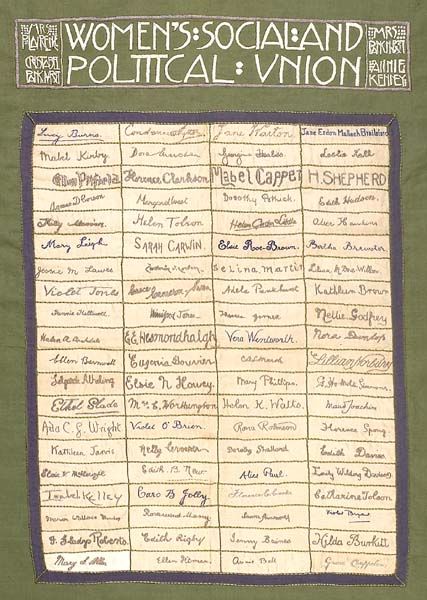

Ten years older than Annie, inspired by the young mill-worker, the Pankhursts and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Lady Constance Lytton joined the WSPU in 1909, one of a small number of upper-class members. She was soon imprisoned for damaging an official car, but, to her irritation, swiftly released when her identity was revealed. In the Museum of London there is a beautifully designed banner, made to raise funds for the WSPU (it was bought by Mrs Pethick-Lawrence for £10). The names of the Pankhursts and Annie Kenney feature prominently in the top corners. Below, embroidered in purple thread, are the signatures of eighty suffragettes who were on hunger strike in Holloway Jail in 1909-10. Constance’s name is at the top of the second column; beside it, in the third column, in strikingly similar handwriting, is one Jane Warton. Wanting to share the experience of her fellow suffragettes, Lady Constance Lytton had re-joined the WSPU, in a new coat, a cloth hat, itchy gloves and scarf, plain glasses, and under a new name. Jane Warton, would not be spared the horrors of force-feeding.

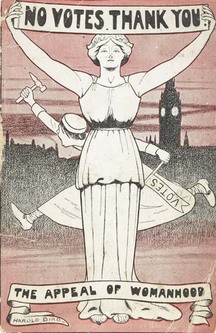

‘Deeds not Words’ was the Suffragette mantra, and though the deeds may not have won over many opponents, they undoubtedly brought publicity to the cause.’Let Them Starve’ railed The Standard, ‘Destruction of an Academy Picture – Suffragette Outrage’ complained the Daily Telegraph, ‘The Henpecking of Parliament – the latest Suffragette outrage’ mocked The Bystander. Their very name had been eagerly taken up by the women themselves, from a contemptuous tag coined in 1906 by the Daily Mail for their more moderate sisters, the Suffragists. It did the activists no harm. Worse was the ‘fake news’ peddled by some newspapers. Many falsely affirmed that in countries where women had been enfranchised the “experiment” had proved a failure. In No Surrender Constance Maud quotes from a fictional article, by a sharp- tongued woman journalist, clearly based on a genuine one, probably several, affirming that women did not want the vote.

Constance Maud joined the WSPU in 1908. Although her ‘deeds’ were less ‘frontline’ than some – she did not set fire to letter boxes, chain herself to railings, or stone cars – she made an important contribution. Her earlier writings had not been without a political message, and she swiftly set to writing for suffrage journals. No Surrender was her ambitious attempt to pull together in a novel the many and complex strands of the movement, covering the background history, describing major public events, setting out the arguments for and against the cause as she heard them in all variety of contexts. She shows us families riven at every level of society, men and women, young and old, constitutionalist Suffragists, activist Suffragettes, and vociferous Anti-Suffragettes. Every point of view has its voice. Every problem is personified, from the overworked factory worker, the ill-treated wife, and the impregnated servant, to the underpaid teacher and the young upper-class woman struggling to explain her beliefs to a kind but old fashioned fiancé. No Surrender is a very full novel, perhaps too full: it is hard at times to keep track of the extended families, parents, children, cousins, in-laws, whose paths cross unexpectedly (and sometimes barely credibly it must be said). The plot, such as it is, is little more than a vehicle for the polemics, some of the minor characters mere mouthpieces. But the thrill of the novel is the certain sense that we are reading raw history, as it happened, with the outcome unknown, heroines and heroes not conclusively anointed, events not yet polished into the linear narrative with which we are familiar.

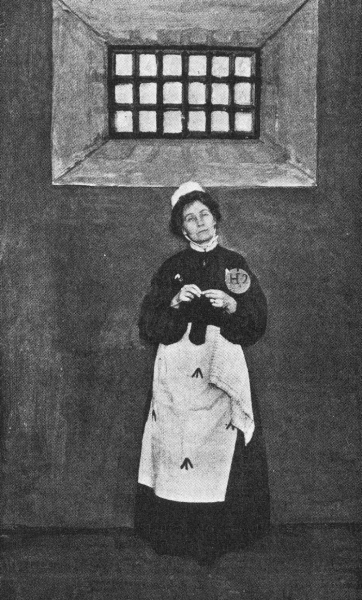

There can be no doubt that Constance Maud knew both Annie Kenney and Constance Lytton aka Jane Warton, and that they are the models for Jenny Clegg and Mary O’Neil. The graphic description of prison life, the cell, the coarse clothes stamped with the prisoner’s arrow, and ill-fitting shoes, the compulsory bath, are clearly drawn ‘from life’, down to the V scratched with a hairpin and coloured with blood – a detail from Constance Lytton’s own time in Holloway. The harrowing account of force-feeding inflicted on Mary O’Neil by three hard-hearted and jaundiced wardresses – ‘”they’re all that impudent, these Suffragitts”’ – and two savagely facetious doctors – ‘”be prepared for her kicking – they always do”’ warns one, ‘”I should go for the nose, it’s less bother on the whole”‘ advises the second – is all the more convincing for the clinical checklist of necessary equipment: ‘tubes, pumps, straps, and cord, steel wedge, an instrument for prising, sponge, towels, a wooden chair, and a big quart jug of beef tea.’ Hard to say which is the most chilling.

We can feel the heat in the fictional Greyston mill, hear the roar of whirling machinery, smell the foul air, and sense the constant underlying fear of being injured, blinded even, by a flying shuttle. Annie Kenney had herself lost a finger, severed by a spinning bobbin. We can hear the bitter anger in Constance Maud’s reflection on the social injustice: ‘Modern invention, so active in other directions, has not yet succeeded in discovering a means of protecting the weavers from these accidents.’ And we recognise the cut-glass voice of the mill-owner’s wife. ‘”They’re used to it”’ is Lady’s Walker’s dismissive response, when challenged about the working conditions by Mary, her cousin’s daughter, and later by own daughter Alice. Her husband shamelessly declares that he will sack any worker who joins the Suffragettes.

Sir Godfrey Walker is a Liberal (the least liberal of all the parties) and fiercely anti; he must seek the support of Jenny’s one-time suitor, a socialist MP, also anti but for different reasons. The politics of women’s suffrage was complicated. Who should come first? Married women, but they would vote with their husbands. Single women, but how would they know who to vote for, and furthermore there were a million more women than men, from which it would follow that women would decide who governed. Women didn’t fight in wars, so why should they vote? Not all men are soldiers, should only soldiers vote? The arguments were fierce but not always rational.

In 1911, when No Surrender was published, the Anti-Suffrage league was still strong. The membership was by no means entirely male. The reasons women had for being against the vote were more varied than those of the men, many, like those in the novel, taking the extreme view that is was against nature, that women would forfeit the chivalry of men (tell that to the mill-workers!), others considering it sufficient that women should have role in local government. A piece in The Persephone Biannually No. 18, ‘Women Against the Vote’, gives an interesting insight into a different more radical case, put by a number of thinking women, for a ‘third house’, where a distinctive feminine voice would be heard, and not drowned out in the bombast of a male-dominated parliament.

At a London dinner party Constance Maud puts together a smattering of politicians, mostly anti, with a number of titled men and their wives, also anti, a bemused French count, Jenny posing as a maid and two young footmen, suffrage supporters (evidently not unusual). The stage is set, the roles determined. A lively and lengthy discussion ensues. The overbearing Lady Thistlethwaite argues that women must look up to men, Mrs Prendergast puts the Nature case, while the politician’s wife, Mrs Weir Kemp, keeps her counsel, ‘she was a good listener, and to all the men, therefore, a charming woman’ – possibly one of those in favour of a ‘Diet of Women’. Lady Walker’s political son-in-law eventually declares: ‘”I think we’ve had enough of this tiresome subject don’t you”‘, to which his neighbour, a strident ‘anti’, replies, ‘”though I loathe it, I can’t keep off it.”’ Other times, a different cause, but isn’t there something disturbingly familiar, in post-referendum 2017?

Constance Maud divides her novel not into chapters but into Scenes. ‘The Dinner Party’ is one, ‘Canterbury Tales’ another: this introduces five very different Suffragettes gathered in a prison cell: the American (five US states, along with New Zealand, Australia, Finland and Norway, had already given women the vote), the older textile worker, the young dressmaker who has served a two-week sentence and can talk about prison, Jenny Clegg, and an elderly widow, a veteran, like her late husband, of the fight for the Married Women’s Property Act. It is a contrived gathering in which the exchange of historical information is barely disguised as dialogue, but nonetheless revealing.

Scene IX, ‘In Middleham Church’ provides some comic relief, as the upper-class congregation slumbers through the young clergyman’s sermon, deliberately altered to promote the cause when he catches sight of Jenny and her companions, until Lady Walker’s older daughter, realising what is going on, frantically and unsuccessfully tries to to signal to her husband, while at the same time bribing her young son with the promise of chocolates to leave the church, only to have him, to her helpless fury, gleefully accept a bunch of purple violets from one of the Suffragettes.

Constance Maud was too close to the events about which she wrote, and too uncertain of what the future held, to introduce humour in the way that Cicely Hamilton, her near contemporary, does in her post-suffragette novel William – An Englishman (Persephone Book No. 1): ‘As a matter of course he was a supporter of votes for women; an adherent (equally as a matter of course) of the movement in its noisiest and most intolerant form. He signed petitions denouncing forcible feeding and attended meetings advocating civil war; where the civil warriors complained with bitterness that the other side had hit them back.’ No-one who had seen the bruised and wasted bodies of Suffragettes and heard their verbatim accounts could have written that.

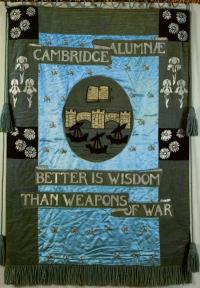

Most of the Scenes are reliant, sometimes to excess, on dialogue, but the final one is wonderfully visual, a theatrical ‘reveal’. Standing beside a young Brahmin law student (little did Constance Maud know what lay ahead for him), Alice Walker watches the Great Procession of women in June 1908, a ‘living river of women’, reckoned at between 200 000 and 300 000, winding round Hyde Park Corner and down Piccadilly. Banner after banner: veterans were followed by the élite of the WSPU, then all those who had been imprisoned for the cause, the University students and the doctors, the textile workers, the post-office clerks, the jelly-makers … the list is endless. At its best Maud’s writing is that of a fine journalist, seeing everything, and telling it in vivid colour.

The Suffragettes were well served by early film, Pathé News being unusually sympathetic. While reading No Surrender I watched the 1913 footage of Emily Davison’s funeral. Most of it is familiar, some used recently at the end of the 2015 film Suffragette, starring Cary Mulligan as a working-class activist. I had seen the crowds, the women in white carrying lilies, the men in boaters, but the final moments were new to me. Her coffin is carried down the steps of St George’s Holborn (not five minutes walk from the Persephone Bookshop). On her plain shroud is sewn a single large broad arrow, the prisoner’s badge of disgrace. Constance Maud would have noticed that.