Late in the afternoon of 16th April 2011, after a 1930s’ tea with musical accompaniment, a commemorative plaque was unveiled at 2 North Park, Moffat, Dumfriesshire, at the house that Dorothy E. Stevenson shared for thirty years with her husband James Reid Peploe. Her fans, DESsies, had gathered earlier in the day for the inaugural Moffat Book Event (MBE is a community group founded in 2010) which opened with the launch of Persephone’s reissue of Miss Buncle Married, introduced by a DESsy from Arkansaw. Officially ‘founded’ only in 1998, DESsies are widespread, and numerous, though not as vociferous as the devoted readers who pleaded in 1934 for the return of Miss Buncle.

‘Barbara Buncle had gone.’ How could Dorothy Stevenson have “written off” the enchanting heroine of Miss Buncle’s Book? Some of the often maligned though far from misunderstood residents of Silverstream had been mightily relieved to see the For Sale notice outside Tanglewood Cottage, only passingly curious as to who ‘Mrs Abbott’ might be, to whom potential purchasers were asked to apply. Not so Stevenson’s readers, eager to know how Miss Buncle would morph into Mrs Abbott. Would Barbara take up her pen again? Where?

But Miss Buncle Married is not another novel about a woman writing a novel about a woman writing … Wandlebury, the commuter belt village to which Barbara and Arthur Abbott move to escape the tedium of Hampstead dinners and bridge, is not Silverstream revisited. Wandlebury has its ‘characters’. The baker’s boy on his rounds introduced us to Silverstream: significantly in view of the plot (such as it is), the deed boxes piled on the office shelves of the local solicitors provide the cast list for this novel. But this is not a fresh exposé of the hidden truths of village life, the seam so brilliantly mined in Miss Buncle’s Book. Miss Buncle Married is a more reflective novel, about growing up; in a very different way from the prequel, it’s a novel about the process of writing; and, primarily, as the title suggests, it’s a novel about marriage, gently humorous, perceptive and generous in its appreciation that there is more than one recipe for a happy marriage; and that for an outsider to understand what binds one person to another is close to impossible.

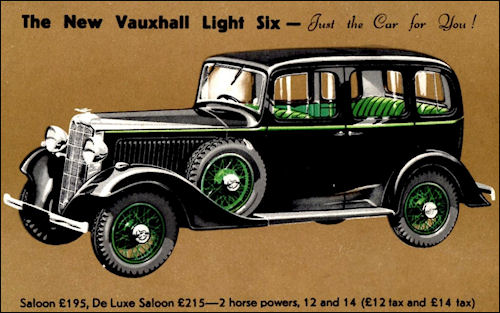

The Rasts who ‘did’ for Arthur Abbott in his bachelor days are an extreme example, held together by regular bickering (sometimes worse), keeping a slate and a squeaky pencil ready on the kitchen dresser for lengthy periods of no-speaks, but they do not make the move to commuter-land. New house, new brooms, new servants: new maids, new cook, new gardener, new rose-beds, and to Arthur’s particular delight, a new Vauxhall car with a smart new chauffeur at the wheel.

A trifle smug, sartorially more than a little vain, well into middle age at forty-three (he considers himself to be ‘getting old’), and thoroughly set in his ways, Arthur Abbott plainly adores his new wife. There is ‘a tinge of heavenly foolishness in his Barbara’, which delights him. He loves her ‘dear funny innocent ways’, and relishes her garrulous moods, ‘it was rubbish, he supposed, if you really analysed it, but what amusing rubbish it was!’. Not at first sight a marriage of equals, but this is the 1930s. DES notes, without further comment, Arthur‘sinking gratefully into the larger (my italics) of the two leather chairs arranged, by his wife, before the fire’. He does greatly respect her appetite for crumpets: ‘Nothing ever gives you indigestion,’ said Arthur proudly; it was one of those things that had drawn him to Barbara Buncle – her amazing digestion – he admired her for it all the more because his own digestion was poor.’ Who could have thought of that?

There is another side to this marriage. Although at meetings with the solicitor, ‘it was Arthur, of course, who did most of the talking,’ he fully acknowledges not only her role in finding their new house and her decorative input, but her very significant financial contribution. His thirty-five year-old (so old then, so young now) ‘child-bride’ is a rich woman, thanks to her literary earnings. Arthur Abbott of Abbott & Spicer (publishers) is in no doubt about her talent, which both fascinates and puzzles him – a chance for DES to examine, in his voice, very briefly but interestingly, the difference between talent and genius. He finds ‘her power of getting under people’s skins’ extraordinary; he is baffled by the gap between her everyday use of language, unsophisticated, banal even, and the piquant fluency of her writing. ‘ …the strangest thing about this strange woman who as now his lawful wedded wife, was that although she understood practically nothing, yet she understood everything’, but he is no hurry to unravel the mystery of Barbara.

Early in their marriage he had sometimes thought he knew her ‘through and through, and sometimes he thought he didn’t know the first thing about her – theirs was a most satisfactory marriage.’ A few months on, he senses he may be beginning to know her, but most importantly he is ‘tremendously interested’ in her. As they approach their second wedding anniversary, comparing them to their bohemian neighbours, the Marvells, Stevenson writes of the Abbotts: ‘They were delighted with each other, not so much because they understood each other better than the other couple but because they misunderstood each other differently.’ This is their secret.

Similar in age to the Abbotts, the Marvells have been married far longer – in the eyes of her contemporaries Barbara at 35 would have been reckoned a fixture on the shelf. They have three children, the eldest, handsome, sickly and largely absent, the younger two delightfully wild, an unmanageable handful for their mousey overworked governess (Stevenson does not minimise the plight of the unmarried) , and fascinating to Barbara. James Marvell is an Artist, his wife an extremely short-sighted beauty, for obvious reasons not a discerning critic of her husband’s work, but ideal as a model, for which role she must massage, exercise, diet and manicure her body, ‘fully aware that, when her body was no longer beautiful, James would insist (with perfect right) upon having a model in the house – and once that started, where were you?’ Where indeed? Arthur considers her ‘either mad or bad’, but DES is clear: ‘Mrs Marvell was a good wife, and perfectly sane and respectable, she had merely been brought up differently from Mr Abbott’s friends.’ James, he reckons ‘a bounder of the first water’ (wonderful thirties slang), but this is in no small measure down to jealousy: his wife and James Marvell spend too long in the studio discussing the difference between the artist, a creature of moods, and the writer, more hunter than builder, very interesting but wholly innocent. With more worldly wisdom than Mr Abbott, Mrs Marvell understands that Barbara ‘could not appeal to, nor satisfy, the physical side of her husband, and, as that was the only side of her husband that Mrs Marvell appreciated, Mrs Abbott could not take anything that was hers.’ DES takes a measured view of the Marvells’ unconventional marriage, not ideal, perhaps but workable: ‘There are quite a number of people in the world who limit their jealousy in this particular manner.’

There is a third match in the air, on which the slender plot hinges – I think I can risk a tiny spoiler here. Arthur’s nephew Sam, twenty-four and with sacks of wild oats still to sow in London, will meet Jeronima Cobbe, niece of Lady Chevis Cobbe the elderly, widowed, ailing, childless, owner of Wandlebury’s ‘big house’, very rich and firmly set against marriage, ‘won’t even have a married butler’. Sam thinks of his uncle as ‘a crusty old beast’, considers that he and his newly acquired aunt have one foot in the grave but can’t help admitting that ‘it really is rather nice’ to see the two of them together. ‘Pretty uncommon’, he thinks, ‘to see old people like Uncle Arthur and Barbara so frightfully gone on each other’. Not that this marriage business is for him, he protests, too much. He will learn. Jerry is a lovely, energetic country girl, not permitted by her father to go to school, but successfully running her own livery business, and her own awkwardly large house (two maids and no electricity), while keeping her wayward brother in check. More restrained, and more clear-sighted than Sam, Jerry recognises that what the Abbotts have is ‘real, friendly love’, to be envied, something to be looked forward too, perhaps in the future.

The Abbotts have married late, both with what we would now call baggage. Arthur’s is most brilliantly and movingly summarised in the history of his morning dress, which he is so pleased still be wearing twenty-three years after it collecting it from the tailor’s. The tiny pen portrait tells his story, and the story of a generation and a class of Englishmen. It is a gem and deserves to be quoted in full.

These garments of Mr Abbott’s were old and valued friends, they had helped him through his first luncheon party, they had given him confidence at his first board meeting, they had accompanied him to weddings galore, and, on two occasions, had aided and upheld him in the discharge of the responsible and onerous duties of Best Man. He had worn them at Lords, year by year when he attended the Eton and Harrow match. They had accompanied him to Ascot and had shared with him the joy of winning a good deal of money and the sorrow of losing considerably more. The morning coat and the topper (but not the other more festive accompaniments) had seen him through a good many funerals, and had helped to conceal too much feeling – or too little.

For five years these, almost sacred, garments had been laid away, guarded by blue paper and a superfluity of moth balls, while Mr Abbott waged war for his country, attired – very differently but almost as becomingly – in a khaki tunic and a Sam Browne belt …

While the War was making a man of Arthur (his words), Barbara was a child in rural Silverstream, living in Tanglewood Cottage, cared for by her nurse, Dorcas. When they meet twenty years later, she is still living in the house where she was born, still cared for by Dorcas, now her maid, and still, in her own eyes, a plain, gawky child, pretending to be grown-up. Arthur is not wrong about her. She is ill at ease with things like late dinner and wine, and ordering commodities, frightened of big dogs and dentists, more in tune with the childish games of little Trivvie Marvell and her brother, whose chatter (absolutely convincing) fascinates her, whose strange, sometimes oddly precocious, questions she treats with utter seriousness, whose misdemeanours she is able to forgive, and whose troubling anxieties she understands.

Almost imperceptibly – Arthur doesn’t notice it – marriage changes her. She settles into Wandelbury, meets the neighbours, chatting with them in the butcher’s or the grocer’s, or in ‘the ice-bound fastness of the fishmongers.’ Eventually the rituals lose their mystery. And she finds a friend in Jerry, not so far removed in age from Barbara, barely more than ten years, and blessed with similar courage and independence of spirit. Barbara offers tea and crumpets and a sympathetic ear, and ‘Jerry enlarged Barbara enormously. In a new friend we start life anew, for we create a new edition of ourselves …’. Surrounded by people who had known her all her life, the older woman had been trapped in her Silverstream self. Jerry Cobbe offers her the chance to create a new facet of herself. Finding and furnishing her own house, a proper two-storey seven-bay house, with a pillared hall, and a graceful winding stair had been the first step. Two years on, the prospect of motherhood has drawn Barbara into ‘the vast regiment of Married Woman’. She ‘feels herself, at last, to be a full grown citizen.’

Mrs Arthur Abbott is no longer ‘an imposter in the adult world’, and yet it’s quite impossible to believe that her own inner child is not still alive and kicking. Has Barbara Buncle quite gone?