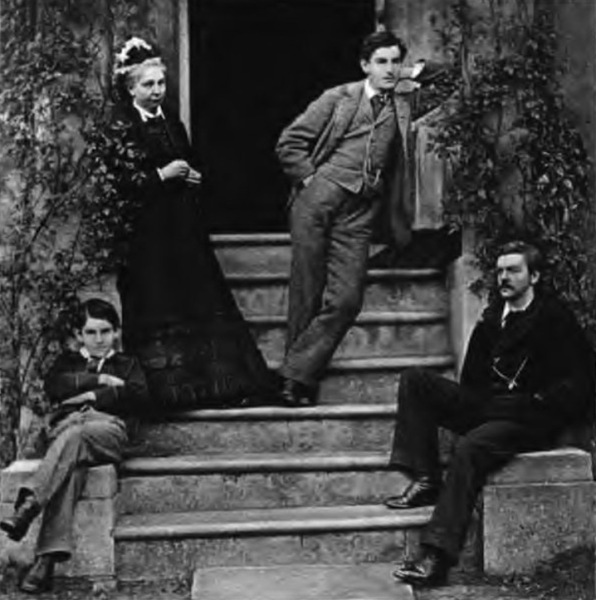

Mrs Oliphant was among the most popular, and certainly the most prolific of Victorian novelists. For almost half a century her name was rarely out of the annual bestsellers list, sharing the billing in 1880 with Henry James, Thomas Hardy, Trollope, George Gissing and Wilkie Collins, and in 1897, the last year of her life, with Joseph Conrad (Nigger of the Narcissus), H.G. Wells (The Invisible Man) and Bram Stoker (Dracula). We are often surprised at the capacity of Perspehone authors to support themselves and their families from their writing, before the era of lucrative film-rights. Margaret Oliphant supported not only her own family, after she was widowed (and possibly before – her husband was an artist, working in stained glass), but also the children of two ne’er-do-well brothers.

Hers was not an easy life, and perhaps we should not be surprised that one of the most used words in these two novellas is ‘comfortable’. The active pursuit of personal bliss is doomed to fail, and likely to leave havoc in its wake. The Mystery of Mrs Blencarrow and Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund make clear that a good house, well run, contented children in reasonable health, a well-conducted, respected business, wealth without opulence, affection uncomplicated by passion should suffice. Passion at any age can be destructive, passion in middle age is liable to be very destructive.

Mrs Oliphant’s message is clear and the two plots are straightforward. A young (by 21st century standards) widow secretly marries her young, virile, servant and is discovered; a fifty year-old man secretly, and bigamously, marries a much younger woman. No apologies for spoilers. The plots require the fictional families to remain in blissful ignorance of their parents’ meanderings from the straight and narrow path of Victorian morality but the clues are there from the start in Mrs Blencarrow and no reader in 2017 is going to be fooled for half a page by Mr Lycett-Landon’s lame excuses in Queen Eleanor for his increasingly extended visits to the London offices of his cotton-broking business. What then did Mrs Oliphant’s contemporary readers make of these novellas, remembering that many would have heard the rumours about Queen Victoria and her ghillie John Brown? Were they surprised, shocked even, by the dénouements, or did the more sophisticated share our knowing cynicism?

Both The Mystery of Mrs Blencarrow and Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund treat with rather extraordinary frankness the issue of sexual desire, of sexual urges extending beyond procreation and the continuity of family and property and strong enough to break the bounds of social convention. Though modest landowners, neither the Blencarrows nor the Lycett-Landons belong to the free-living, free-loving fin de siècle aristocracy: their moral code is that of the law-abiding, church-going middle classes. Ironically, in both cases it is the perceived pressure on the lovers to regularise their situations that proves their undoing. With no intention of granting her husband any social advantage or status, Joan Blencarrow boldly marries for sex.

But if she had she not signed the blacksmith-priest’s register at Gretna Green, the ‘mystery’ would not have been uncovered. And things would have gone better for Robert Lycett-Landon had he not felt obliged to ‘marry’ young Rose, for as old Fareham, the senior partner in the well-established and highly thought of Liverpool firm, explains to the real Mrs Lycett-Landon, ‘when a man has put himself within the reach of the law he is powerless, and we have him in our hands’.

Old Fareham is ‘triumphant’, Mrs Blencarrow’s nemesis, Mrs Bircham, able at last to challenge the elegant and detested paragon of virtue, cannot conceal her pleasurable excitement, nor dim the malicious light in her eyes as she sneers at the agent Brown, ‘I suppose that’s the man.’ Yet Mrs Oliphant’s coolly observant narrator has no sympathy for the cold-blooded, sexless standard-bearers who take more delight in seeing their neighbours fall from grace, than in seeing the rules they hold so dear upheld.

Robert Lycett-Landon is punished, not by his wife, nor by Rose (we don not learn if she discovers the truth, and if nothing else she has a nice new house of her own, though the garden is ‘common’) but by the passage of time, the distancing of his children and the loss of his own house. A stout, embarrassed old gentleman shuffling his feet, he behaves well at the last, claiming nothing back, though his gentle wife, distressed by his downfall, might have allowed it. Joan Blencarrow leaves the house and the estate, but lives happily abroad, having seen off the husband who had after all proved so much less than satisfactory. The Lycett-Landon business and the Blencarrow estate will live on in the hands of the next generation. Horace Lycett-Landon, the ‘merchant prince’, emotionally unimaginative – he can picture no worse sin on the part of his father than some financial impropriety – will continue the cotton-broking business. Reginald Blencarrow will take over the estate, which had in truth been well managed by his mother and her handsome agent. Horace and Reginald are the sons of strong women.

It is worth noting the date of publication, just eight years after the passing of the Married Women’s Property Act. Would Joan Blencarrow have risked an uncertain marriage knowing that it would entail the loss of her estate? Would her husband have written a different will? Would her brothers have kept a closer eye? 1882 was a watershed year and in their way both these novellas are quite feminist in tone. Women are by far the strongest characters, for good or ill. Mrs Bircham leads the pack in ‘exposing’ Mrs Blencarrow, and her headstrong daughter, Kitty, unimpressed by his dully unromantic choice of transport (train rather than post-chaise) for the journey to Gretna Green, brooks no dithering from her young swain, Walter Lawrence. Demonstrating what the narrator archly refers to as ‘a man’s faculty for abandoning his partner in guilt’, he will further disappoint his bride when he fails to back her up on the contents of the blacksmith’s marriage register.

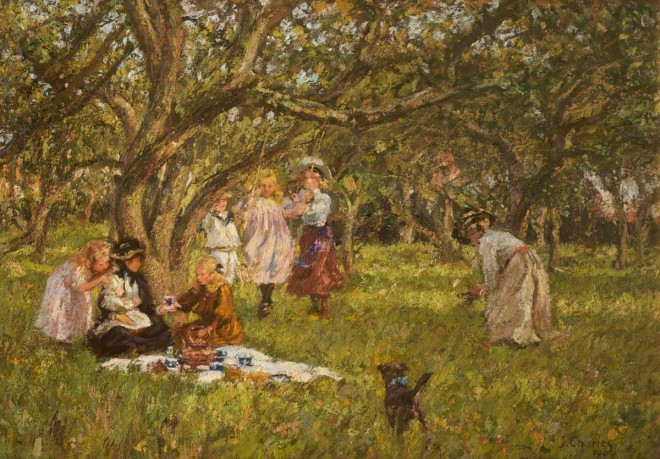

Liberated by widowhood or the pressure of business from the demanding presence of the Victorian pater familias, Mrs Blencarrow and Mrs Lycett-Landon prove to be excellent parents with a talent for enjoyment. The first ensures that the family house is always well-ordered, ‘ringing with pleasant noise and nonsense when the boys came home, quiet at other times, though never quite without the happy sound of children.’ The second, allowing ‘a little loosening of the bonds when the head of the house was not there’, happily dispenses with dinner, ‘to suit a country expedition, a garden-party, or a picnic, which was a thing impossible when papa’s comfort was the first thing to be thought of.’ Mrs Oliphant is something of a proponent for the one parent family, from experience no doubt.

Women manage well enough on their own. Is marriage worth the candle? Just, judging by the somewhat jaundiced portrait of Kitty Bircham and Walter Lawrence, whose own Gretna Green escapade triggers the plot of Mrs Blencarrow: ‘That match turned out, like most others, neither perfect happiness nor misery. Perhaps neither husband nor wife could have explained ten years after how they were so idiotic as to think that they could not live without each other; but they got on together very comfortably, all the same.’ Comfort, once again. Comfort, in the sense of undisturbed ease, trumps happiness. Tidy concealment beats painful explanation. Towards the end of Queen Eleanor and Fair Rosamund the wise narrator comments: ‘The Lycett-Landon business remained a mystery, and after a while the waters closed tranquilly over the spot where this strange shipwreck had been.’ Who would dare to write that now?