I picked up Amours de Voyage knowing less about Arthur Hugh Clough, than about his sister, Anne Jemima Clough, the first Principal of Newnham College, and about his younger daughter, Blanche Athena, another powerful defender of the cause of women’s education in the late nineteenth century.

What, I wondered, was a verse novella by a Victorian poet, best known for “Say Not the Struggle Nought Availeth”, which one might expect to find along with “Fight the Good Fight” and “Onward Christian Soldiers” under the tag ‘muscular Christianity’, doing in the Persephone Catalogue. “Say Not The Struggle”, said to have been a favourite of Winston Churchill, is the only poem by Arthur Hugh Clough in my 1900 Oxford Book of English Verse. My 1939 edition has just two. His popularity is increasing; my most recent edition, 1975, contains five, three of which might have been considered for the ‘companion’ volume of Light Verse, and which are astonishingly modern in tone, as Julian Barnes makes so clear in his introduction to Amours de Voyage.

Published posthumously in 1862, The Latest Decalogue is a brilliant satirical and deeply irreligious take on the Ten Commandments, whose most famous couplet

“Thou shalt not kill; but need’st not strive/ Officiously to keep alive.”

is invariably quoted wholly out of context, more likely to be attributed to Hippocrates than to a mid nineteenth century poet, who had lost his faith and took a dim view of Victorian hypocrisy, as the following lines make abundantly clear:

“Do not adultery commit;/Advantage rarely comes of it:/ Thou shalt not steal; an empty feat,/ When it’s so lucrative to cheat.”

It is not only the metre that brings to mind Belloc’s Cautionary Tales. A second posthumously published poem, There is No God, is similarly sharp and astonishingly contemporary in tone. The final verse reads:

“And almost everyone when age,/ Disease, or sorrows strike him,/ Inclines to thin there is a God,/ Or something very like him.”

Ever ready to expose the hypocrisies of his period, Arthur Hugh Clough was by all accounts a thoughtful, gentle, humorous, troubled man, whose religious doubts cost him a comfortable life as an Oxford don, hard to believe in our secular age. He held women in unusually high regard.

While still at school himself, he made it his business to ensure that his, only slightly, younger sister should not miss out on education like so many of her peers. He encouraged her to read Shakespeare and to continue her study of German (good enough to translate Schiller, Goethe and Kant).Latin and Greek were added to this rigorous curriculum. They travelled together in England, and some years later embarked on a two-month tour of Europe. Clough took an unexpectedly conventional view of the dimness of prospects for Annie, as he called her, unmarried in her thirties, writing as much in a letter to their mother, but he clearly appreciated the company of a well-read and intelligent woman. Blanche Smith later fulfilled these requirements. A cousin of Florence Nightingale, with whom he worked on hospital reform, he first met her in 1850. They married in 1854. Not a whirlwind romance: Arthur was cautious. He valued her intellect from the start, but did he love her, could he commit? What if he didn’t? How might Blanche feel?

The parental and social pressure on young girls to find a husband was an effective barrier to friendship between the sexes. How many Persephone heroines fall victim to that pressure, and not only the heroines. Remember Martin Lovell in Helen Ashton’s Bricks and Mortar (Persephone Book No.49), who, unable to resist the force of Mrs Stapleford, finds himself coerced into an unhappy marriage with her daughter, Letty.

Claude, a self-centred, indecisive, snob, far less sympathetic than Martin Lovell, arrives in Rome in turbulent times, during the fall of Mazzini’s short-lived Roman republic, besieged by invading French troops. While there he makes the acquaintance of the Trevellyns, mother and father travelling with their three daughters, a courier, and a fiancé. Arthur Clough had himself witnessed the bloody skirmishes of 1849 (a bit of a revolutionary voyeur he had spent several weeks in Paris the previous year during the fall of the July monarchy), and some of Claude’s dismissive comments on what other Grand and not so grand tourists, considered, wrongly in his opinion, to be the glories of Rome, clearly echo Clough’s own. In a letter to his mother the poet summed up the city as ‘a rubbishy place’, the word he has Claude use, underwhelmed by St Peter’s (too many Bernini sculptures), the Forum (‘an archway and two or three pillars’) and the Coliseum, impressive only by reason of its size. Is Amours de Voyage autobiographical? There is no record of even one amour on Clough’s part, and if Claude is a self-portrait, it is a very self-deprecating one. A man of principle, but not an arrogant man judging by the drawing we have of him, it may have amused Clough to paint a caricature of himself, revealing and exaggerating some of his all too human weaknesses.

Faced with two big decisions, whether to join the republicans against the French, and whether to declare his love for Mary Trevellyn, Claude ducks both. The Romantic anti-hero, the man of in-action, he closely resembles that archetype of Russian nineteenth century novels, the ‘superfluous man’. Preferring in prospect the role of uncle to that of father, better suited to ‘peaceful avuncular functions’, and complaining that

“No sort of proper provision is made for that most patriotic,/ Most meritorious subject, the childless and bachelor uncle”

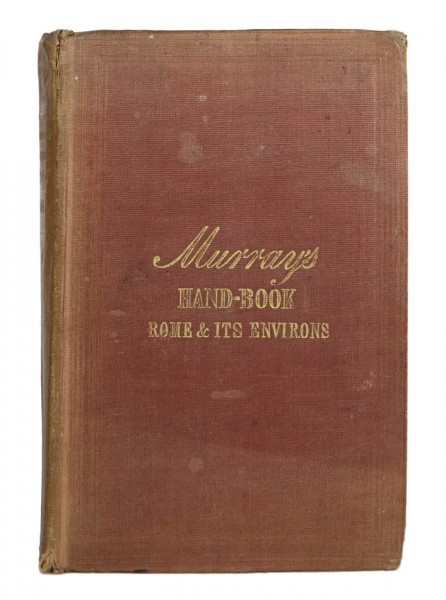

he is one of life’s onlookers, and that at a distance, and only so long as his routine is not overly disrupted nor his creature comforts denied. When the battle begins in the streets of Rome, he repairs to a café, clutching his Murray’s Handbook, to whose “itinerary” he slavishly adheres – ‘… today is their day of the Campidoglio Marbles’.

Irritated by the lack of latte for his Caffè-latte, and by the inattentiveness of the waiter, he follows the tourist crowd to the Pincian Hill, where he is disappointed by the view of the fighting – ‘Smoke, from the cannon, white, – but that is at intervals only’ and worried about the possibility of rain. Weary of watching, he hurries home, ‘to make sure of my dinner before the enemy enters’, pausing only briefly ‘…. to minister balm to the trembling/ Quinquagenarian fears of two lone British spinsters’, his brief moment of gallantry.

Hardly heroic, but then Claude never made any pretence of altruistic heroism; ‘On the whole, we are meant to look after ourselves…’. Quoting Horace’s words made so poignantly famous over half a century later by Wilfred Owen, Dulce et decorum est … he concludes:

“Sweet it may be and decorous, perhaps, for the country to die; but,/ On the whole, we conclude the Romans won’t do it and I shan’t.”

He justifies his political apathy, listing five good reasons for not fighting: he has no musket, and if he had one he wouldn’t know how to use it; he’s busy studying the Vatican marbles; he owes his life to his country, and the fourth reason – he forgets. His one close encounter, which might have been a rite of passage had he been growing up in any meaningful way, is that he sees a man killed, or maybe he doesn’t, and maybe the man hasn’t been killed – the fog of war. A man? Maybe a priest? A man in black. Claude is wearing black and could be mistaken for a priest. Time to run, ticking off a few Murray’s “chief objects of interest on the way”, loftily concluding that the Coliseum, derided at first, ‘at the full of the moon is an object worthy a visit’.

Amours de Voyage is written in letters, Claude’s being addressed to his friend Eustace, whose responses we can only guess at, but who must either be extremely tolerant or share the same outrageous views. He would seem to be a more worldly fellow than Claude, no more eager for the fray, but more experienced in matters of the heart and urging more action on that front. For Claude is as passive in love as he is in war. His first meeting with Mary is hardly the coup de foudre. He falls in with Trevellyns because he is ‘slow at Italian’ and has few English acquaintances, generously tolerating Mrs T’s ‘mercantile accent’, trying not to mind the lingering ‘taint of the shop’, while enjoying ‘the horrible pleasure of pleasing inferior people.’

What a monster! But what an entertaining monster, and, perhaps because Clough has with disarming honesty put something of himself into him, not wholly unsympathetic. We want Claude to do something, for himself and for the delightful Mary Trevellyn, whom we know from her postscripts to her sister Georgina’s letters, from her letters to her governess, and from Claude’s own letters, which demonstrate a confusion of admiration and nervous condescension. An innocent assuming the voice of a sophisticate he is troubled by inadmissible stirrings of sexual desire, ‘this demon within us’, he can barely understand his own feelings, and projects received wisdom onto hers, convinced that women prefer the vehement hero to the timid sensitive soul. For her part Mary correctly suspects that Claude would like her to woo him, and equally correctly fears that he would be shocked if she were to do so. Clough’s insight into the mind of a young woman is both clear and tender, coloured by some of the guilt that he may himself have been feeling about his own delay in committing to Blanche. Mary Trevellyn’s touching description of how a love affair, perhaps better to say marriage, with Claude might evolve is wise and hardly optimistic:

“She that should love him must look for small love in return, – like the ivy/ On the stone wall, must expect but a rigid and niggard support, and/ E’en to get that must go searching all round with her humble embraces.”

What a startling image of Victorian marriage. Is the poet writing about himself?

Amours de Voyage is a sad story of missed opportunity and misunderstandings, a loveable heroine prevented from acting by social convention, and a tiresome anti-hero comically incapable of action. One wishes it might turn out well for them. It is not by Persephone standards a page-turner, but one which rewards several re-reads. The comedy is so light that it is easily missed, the psychology subtly concealed. In an 1852 essay Clough declared his preference for verse ‘which dealt more than at present it usually does, with general wants, ordinary feelings, the obvious rather than the rare facts of human nature.’ Not a bad description of some of the most loved Persephone Books.