‘Things happen against our will. Always being driven and we follow – voices – they promise us all sorts of things. We think we are moving towards some strange rich carnival and follow follow follow. Then suddenly we find ourselves left alone in a dull crowded street with no-one caring for us and our lives unneeded.’ The message of Winifred Holtby’s novel, and indeed of her all too short life – she was only 37 when she died in 1935 – is that there is another way; that the voices though they will not be silenced need not be heeded. Only 26 when she wrote The Crowded Street, she had learnt, perhaps been taught by her strong mother, her headmistress, or her courageous friend, Vera Brittain, that what matters ‘is to take your life into your hands and live it’.

‘Gallivanting off to college’, is the shocked response of the mothers of Marshington to Delia Vaughan’s plans to go to Newnham; ‘distinctly lacking in a sense of duty’, is their damning verdict. Fortunately for Delia, her widowed father, Marshington’s vicar and sole intellectual, doesn’t share their views.

Would her late mother have encouraged her to go to Cambridge? Mrs Marshall Gurney, the most vocal of the chorus, rather suggests not: Mrs Vaughan ‘was a delightful woman, one of the Meadows of Keswick’, the sort of woman, is the clear implication, who would not have argued with Charles Kingsley’s instructions to sweet maids to ‘be good and let who will be clever’. Delia is a free spirit, modelled on Vera Brittain, and in part on Winifred herself, who bore little resemblance to her central character, Muriel Hammond: according to Vera Brittain, Winifred used to say of herself that she was ‘one of the very few women who went to Oxford because their mothers wished it’. Muriel is a dutiful shrinking violet, unkindly but accurately summed up by Delia as an ‘intellectual idealist of limited capacity, not too much will-power, immense credulity and ridiculous desire to live up to other people’s ideas of her, stuck in Marshington.’

The Crowded Street opens before the First World War, in deeply provincial England, in a still semi-rural, ugly but fiercely respectable suburb of Hull, where social boundaries are clearly drawn, and social conventions unchallenged. The mothers of Marshington do their best to ensure that they remain so: Mrs Marshall Gurney, Mrs Cartright, Mrs Lane, Mrs Parker, Mrs Waring, Mrs Hammond and more, tirelessly arranging and attending dances, picnics, tennis parties, tea, dinner and bridge parties with one, unstated aim, the finding of a partner for their daughters. Motherless, Delia refers to it accurately and disparagingly as ‘sex-success’; unsurprisingly she is mistrusted and disliked by the older women, not for her brains or her looks, although she outshines their daughters in both, but for her brave disregard for the ‘rules’.

Failure to secure a partner for the next waltz, felt like a disaster. Failure to secure a partner for life was a disaster for a great many women. The one escape route from the family home was barred to them; they were a financial burden on their fathers and ‘an outward and visible sign of failure’ for their mothers. We have met these women in other Persephone Books, women for whom years of caring for ageing parents are followed by years of loneliness. Muriel need look no further than her own Aunt Beatrice, a pathetically persuasive advocate of marriage at any price: ‘It’s when you grow older and the people who needed you are dead. And you haven’t a home nor anyone who really wants you … I sometimes pray that the good Lord won’t make me wait here very long – that I can die before every one gets tired of me, and having me staying round … Oh, Muriel, my dear, if ever a good man offers you the chance of a home, of children, of some reason for living, don’t throw it away, don’t, don’t.’ If only all men were ‘good’.

One marriage in which the flaws are all too apparent to Beatrice is that of her sister, Muriel’s mother, Rachel. Its bumpy history is brilliantly summarised in the rings that she slips onto her fingers, ‘the diamond half hoop, her engagement ring. Arthur had been generous but unoriginal … Here was the emerald that he had bought during their honeymoon. Here, the ruby set between two splendid pearls that he had bought her after that affair.’ Rachel had married beneath her, for love, a bluff, red faced, prosperous manufacturer of sacks, with plenty of ‘new’ money, and a fine new house, the ‘best in Marshington’. Miller’s Rise has an overstocked kitchen garden and ‘stiff borders by the drive, wherein begonias, lobelia and geraniums were yearly planted out, regardless of expense,’ – Holtby so cleverly invokes the critical tones of the gardening snobs. In spite of Arthur Hammond’s eye for a pretty barmaid, or a young governess, having fought a determined tactical, and largely successful, battle to regain the social ground lost in her youthful folly, after twenty-five years Rachel still finds herself drawn to to his ‘rough mastery’ and comforted by his ‘great arms’. There is a passionate intensity to which Beatrice is blind, and which their daughters cannot yet understand.

The messages given out by Rachel and Arthur Hammond to their two daughters have been confusing. Arthur’s business acumen has provided considerable material comfort, a good enough education, and fine dresses, but Connie, Muriel’s younger and more spirited sister, who has more, perhaps too much, of her father in her, has, to her astonishment, seen her own entrepreneurial ambitions dashed – for one’s daughter to be running a chicken farm could undo years of careful manœuvring on the social battle front. Muriel, convinced that she has a duty to remain at home to help her mother, only belatedly understands that she is in the way: not only is her continuing presence humiliating for her parents, all too visible proof of lack of sex-success, but she, the unmarried daughter, is intruding on their imperfect but enduring marriage. Connie’s eventual escape had been dramatic and tragic, but at least it was brave, while Muriel has let her youth pass by, dusting the drawing room, handing cakes at her mother’s tea parties, helping her with the Mothers’ Union accounts, and intermittently pursuing a childhood interest in astronomy ‘with the help of three second-hand textbooks and a toy telescope.’ So sad.

In Aunt Beatrice’s dancing days, long before the World War took its cruel toll of available young (or not so young) men, single women had already outnumbered single men by about one million. By the time she delivers her impassioned but unrealistic advice to her niece, the figure is closer to two million. Muriel is thirty and the parting homily delivered by her headmistress fifteen years earlier, ‘to serve first your parents, then I hope your husband and your children, to be pure, unselfish and devoted …’, has passed into history, leaving a hollow ring.

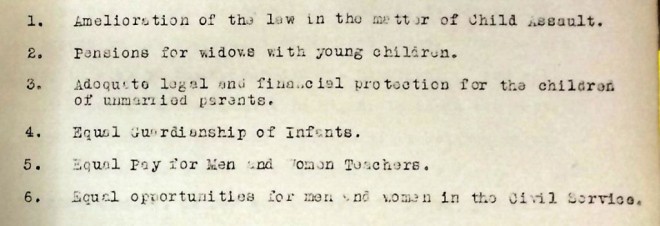

Ten years or so younger than Muriel, Holtby herself and her contemporaries, middle-class girls of moderate means, would leave their, perhaps more enlightened, school with a very different message: a professional career was in their sights. The War had taken their husbands, but had opened up new possibilities, (‘a pity that should have been left to wartime’, Delia observes sharply when this is pointed out) and led to a kind of respectability in numbers. As one among two million the single woman need no longer hang her head in shame. Muriel will find many fellow souls in the ‘crowded street’. But not in Marshington.

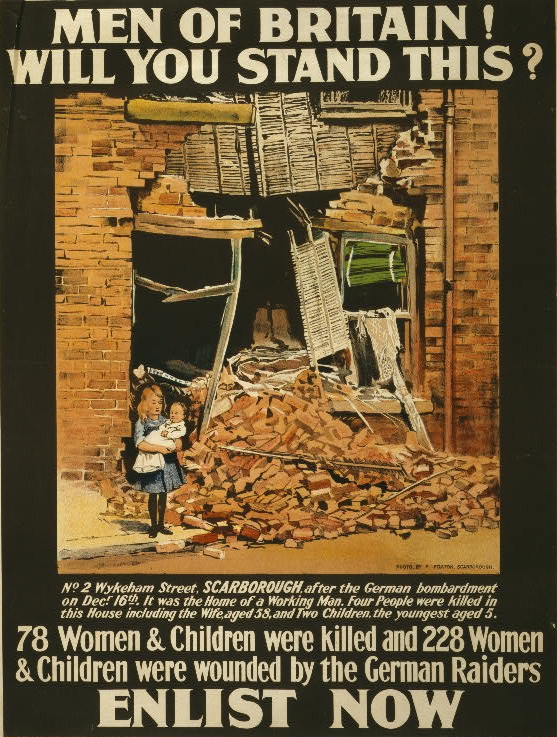

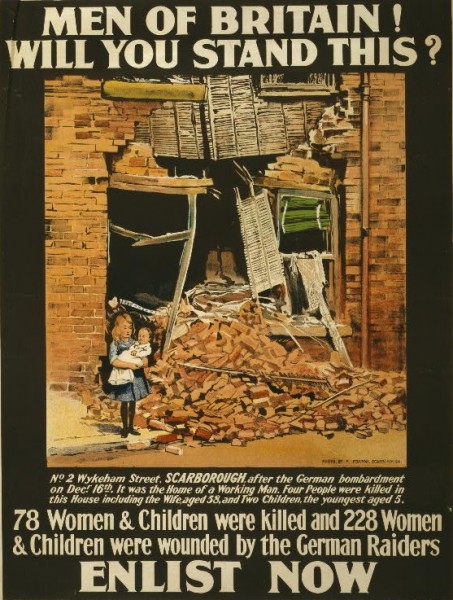

The war has barely touched the East Riding, apart from the unexpected shelling of Scarborough, a brilliant set piece, one of many, which, by focusing on the everyday detail Holtby turns from drama to comedy. An aged aunt must be carried to safety; ‘they all bundled aunt Rose’s shawls downstairs into the car, hoping she was still inside them, for they could see nothing of her.’ Running for their lives along the Esplanade, Muriel can think only of her stockings falling around her ankles; her mother appears to be bouncing like a rubber ball; Uncle George offers sound masculine advice, ‘He performed Sandow’s exercises every morning before breakfast and was therefore an athletic authority.’ The Great War proved to be ‘only a grocery shortage here, and an influx of officers’, sneers Muriel, much later, cruelly disregarding the deaths, envying the bereaved ‘the dignity of loss’. Winifred Holtby must have observed many and varied reactions to the deaths of lovers, friends and brothers and is not unsympathetic to this seemingly perverse response.

Muriel needs to leave the family home if she is to grow up, and find herself as a person, but she lacks the will. She remains convinced that unlike men, who do as they like, women must ‘just wait to see what they will do … Things happen to us or they don’t’. A dreamer as a child, she must find ‘the courage of her dreams’. Help comes from two unexpected sources: her father, who appears to have taken little interest to date – ‘Do what ye will with the lasses. If they’d a been lads, I might ha’ had summat to say’ – understands that what she needs is an income of her own, and Delia Vaughan, who, for her own selfish reasons, takes her out from under the ‘shadow’ of Marshington.

A little older, Delia had in Muriel’s eyes, and heart, long been outshone by her school-friend, the exotically beautiful, exotically named, well-connected and effortlessly sophisticated Clare Duquenne, not a rôle model, but an unattainable ideal. Muriel loves her from the first, is dazzled by her, and cannot see her destructive quality: ‘Her vivid dress had caught all light and colour from the room, and held them, glowing with barbaric splendour.’ A black hole of a person, a will o’ the wisp. Clare cannot, will not help her. Nor can Godfrey Neale, to whom she had secretly given her heart at the age of eleven. Handsome, rich, by Marshington standards, well-educated, also by Marshington standards, his rural roots run deep. A life without hunting and shooting would be no life at all. Conceited and dull, he is, by Aunt B’s reckoning, a ‘good man’, and will doubtless find women falling over themselves to be ‘his hostess, and look after his home and all that sort of thing.’ But that woman will not be Muriel. Godfrey would force her to remain in Marshington. Clare could not help her leave.

Dismissing Muriel’s intellectual self-deprecation as cowardice, Delia gives her courage. She rates industry and a sound constitution more highly than brilliance as necessary qualifications for Newnham, but she puts the highest value on courage. ‘The whole position of women is what it is today, because so many of us have followed the line of least resistance, and have sat down placidly in a little provincial town, waiting to get married. No wonder that the men have thought that this is all that we’re good for.’

Women, then, must take some of the blame. Delia is not especially kind to Muriel, whose first months in Bloomsbury are barely less domestic than her life at Miller’s Rise, caring for Delia while she pursues her work for world peace and women’s equality. She has not opened doors, but she has shown Muriel where they are, and made her see that, though a perfect marriage is a splendid thing, it does not follow that the second best thing is an imperfect marriage. What matters is ‘to take your life into your hands and live it.’ With good reason the short final chapter of The Crowded Street is titled ‘Muriel’.

As I was writing this, I read by chance a recent article by the Senior Tutor of Newnham, Terri Apter, in which she admits to frustration at the over-use of the word ‘confidence’ (or lack of) in the context of women’s education, far preferring ‘courage’. She quotes the American academic, Carol Gilligan, visiting professor at the Cambridge Centre for Gender Studies, who defines courage as ‘the ability to speak one’s mind by telling all one’s heart’. Winifred Holtby might have written that, almost a hundred years ago.