‘Plucky’ isn’t a word you often hear now. Did it somehow go out of fashion, in the hedonistic 1960s, the selfish 1970s, years of ‘letting it all hang out’, of putting all one’s chips on personal fulfillment, when to grin and bear it was not just risible, but wrong? If the bed you have made proves uncomfortable, don’t bother lying on it, was the message: make a new one. Pluck seems to be a rather old-fashioned quality: courage not in the face of great danger, but in the face of difficulties, determination in trying circumstances, the kind of courage and determination that we admire and warm to in so many (all?) Persephone heroines. Patricia Crispin, heroine (in every sense) of Princes in the Land is plucky.

So, it would seem, was Joanna Cannan. Married in 1918 to, Captain Harold Pullein-Thompson MC, a badly injured veteran of the First World War, it soon became evident that she was going to be the principal bread winner for the growing family. Between 1922 and 1958 (she died in 1961) she published more than forty novels, sometimes two or even three in one year, including a number of detective novels, and nine ‘pony books’, a genre which she is credited with having invented, and which was perpetuated by her three daughters, Josephine, Diana and Christine Pullein-Thompson (their brother Denis was also a writer, but chose to use his mother’s maiden name – perhaps to avoid identification with the ‘pony-club’). Any reader familiar with the genre – and I confess to having been a young devotee – will know that ‘plucky’ is the pony-book adjective. To be fair and graceful cuts no ice; rosettes are awarded for bravery not for beauty. A girl must know ‘how to ride at her fences’.

Young Patricia Crispin is a pony-club heroine from central casting, with her carroty hair, her hoydenish (another underused word these days) ways, her ability to run, jump and climb, and her physical courage. The despair of her ghastly mother, who ‘lived between the four walls of seeing and hearing’, thinking only of ‘clothes, money, manners and social functions’, she wins the heart of her delightful grandfather, Lord Waveney, who has come through tragedies well outside the range of the gymkhana, and whose private life would have disqualified him from so much as a walk-on part in They Bought Her a Pony. ‘He wasn’t sober, pious or chaste; but he was honest, charitable, unselfish, long-suffering and brave.’ Fortunately his grand-daughter has inherited his qualities, for this is no pony book, but a very grown-up account of a rapid and rocky trajectory from an upper-class childhood rooted in an already faded Edwardian era, through a socially rebellious, and far from easy marriage, and the joys and disappointments of motherhood: moving, and ultimately uplifting because Patricia doesn’t allow herself to dwell on her sorrows for very long at any point, though there are many on which she might be forgiven for dwelling, and Joanna Canaan quickly raises her readers’ spirits, eliciting a wry smile with a cutting comment or a sardonic aside.

Fleshing out her characters with telling details, wittily breathing life into the most minor, Cannan does not linger over history or narrative. She is mistress of ‘show, don’t tell’, never showing more than we need, sometimes deliberately tantalizing with a dropped name, or a teasing loose end. The ‘back history’ of the Waveneys of Hulver takes up barely a page and a half, cantering through the deaths of three sons, the tidying away of a certain widow – ‘he had persuaded the widowed Mrs Featherstone that … she would find a prettier cottage and a gayer life elsewhere’ – , and the reluctant arrival of a daughter-in-law in reducing circumstances– ‘Blanche had packed up and left with tears the last and smallest [my italics] of the furnished houses’. The wandering widow in four words!

The First World War is covered in a single paragraph: the tragedy – names on the war memorial; the exhilaration of living in the present – oysters and champagne at the Ritz; the drabness of the aftermath. This is not the Great War of the poets, or the historians, but of a young woman, like countless others, meeting the ups and downs of daily life. There is a big picture, but Cannan knows that for most it is more often occluded by the small picture. She lists, not battles or casualties, but the price of butter,and eggs, not individual deaths but properties sold to meet death duties. She doesn’t celebrate the victory or mourn the loss of a generation, but with remarkable frankness, some bitterness and clearly from her own experience, describes the new order, in which ‘… purses closed, faces hardened, jokes fell flat’.

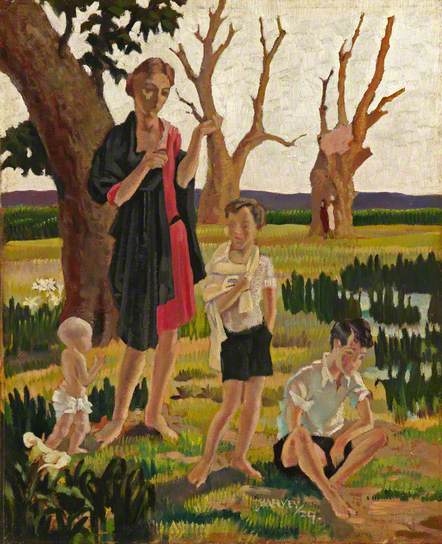

For Patricia and her husband, Hugh Lindsay, academic, son of a Peebles builder, upwardly mobile, but harbouring a self-protective contempt for the class into which he has married, this is where family life begins. Patricia must complete the transition from childhood to motherhood, from a privileged and (thanks to her doting grandfather, not her bitter mother or her bullying nanny) happy childhood in the lost world of Hulver, to a life of ‘cooking, sweeping, dusting, scrubbing, washing, pushing the pram’. She becomes competent at the first five, to which she adds baking and darning and knitting, but it is the pram pushing, tiring as it is, that makes up, more than makes up, for her exile from Arcady. The children are her consolation: ‘for the beauty and the love and the fun and the hope that they were, this shortened step, these aching legs, this end to adventure was a small price to pay.’

Cannan makes brilliant use of what grammarians call ‘free indirect speech’, so that almost without realizing it, we find ourselves inside the heads of her characters, hearing their thoughts, seeing through their eyes. Most especially we find ourselves inside Patricia’s head, inside her body. We feel her aching limbs, and when she makes up her mind, to lie on the bed she has made for herself, to stop looking back, ‘to give up telling the children about Hulver, and teaching them hunting noises, and carrying carrots in her pockets’, we sense her hand digging into the unfamiliar emptinesses of her coat. The inside of Hugh’s mind is less congenial. We do not discover a doting father. He is pleased that his children look tidy, but requires little more of them. Deploring, and resenting, his wife’s upbringing, he is blind to the fact that it is that which has given her the strength to take on the challenge of life with him. Assuming that women are adaptable, and unaware of her sacrifice, ‘he took for granted and sincerely loved the admirable helpmeet that life had broken for him’. The equestrian ‘broken’ is so apt, and so sad.

Hugh has not had to adapt. His journey has been very different from Patricia’s. He has not had to take the ‘jars’ (Lord Waveney’s word) that she has. His path to academic success is smooth, and once he has achieved the summit of his ambition, he can relax. The Oxford professor, released from his jealous disapproval of her forbears, can finally spare a thought for his wife’s needs, giving her a house in the country with land and the all important stables. Allowing at last that his children might have some of the Waveney genes he buys them ponies, and guns. He has reached his goal, and nothing else matters, not his dentures, nor the fact that passion has gone from his marriage, nor the future of his children, who have turned out surprisingly different from what he expected. He is sad that Augustus, the elder, doesn’t enjoy Latin verse, and that the younger prefers Newbolt to Milton, but resigned to the fact the one marries a dull, stupid woman, and the other joins a ferociously muscular Christian movement, while his daughter prefers cars to horses. Because had set little store by their success, they do not greatly disappoint him.

How different for Patricia, who has no ambition for herself, who has vested all her dreams for the future in her children, her ‘Princes in the Land’. Children have been her life’s work, but that career path is bumpier and less clearly signposted than academia. The early years, so tiring at the time, prove in retrospect to have been the happiest, so much easier than the later ‘quarrels and complexes, sulks and selfishnesses’, ‘… for though your legs ache, you can still go on walking, whereas tact, patience, wisdom are apt at any moment to forsake you.’ Still, however trying, the job is worth doing, for what else can make middle-age bearable, compensate for the false teeth and the dull husband. ‘If you’ve got children what does it matter if you grow old?’

Patricia, as it turns out, is wrong. The job of parenting had to be done, and she did it as well as she was able, with little help from Hugh, single-mindedly focused on his own career, but the rewards prove more limited than she had so confidently expected. Augustus, Giles and Nicola do not turn out as she had dreamed, ‘… these weren’t the children for whom she had given up fun and friendship, worked, suffered, worried, taken thought, taken care, done without, suppressed, surrendered and seen her young self die.’ She had expected too much. We may find Hugh selfish, criticise him for long ago carelessly burying the red-headed hoyden he had married, but it is hard not to sympathise a little when he tries clumsily to comfort her with the thought that most parents are disappointed in their children. Why, he wonders, but, tactfully, does not ask, does she go on fighting?

‘She was forty-six, with scarcely a tooth left in her lower jaw; she was disappointed in her children; her husband no longer took any sexual interest in her …’. But the young rider to hounds deep within Mrs Lindsay, tamed by life, and caged, is not after all dead. Chance takes her past a burning cottage. A child is trapped inside. With blind courage she clambers in, takes the girl in her arms and jumps. The child turns out to be illegitimate, mentally deficient, and not greatly loved, but Patricia has rescued her. The symbolism is obvious, but no less touching for that.

Plucky Pat Crispin can still ride at her fences. There is life after motherhood. Patricia is able to let her children go their own ways, not in the ways that she had planned for them, while she, a woman her sons and daughters seem hardly to know, and her husband thinks too old, gets back into the saddle, and finds happiness of her own, small but real.

I came across a first edition of It Began With Picotee, the first of Joanna Cannan’s daughters’ pony books. Attached to it was the bookseller’s note: ‘Hardback with very good dust jacket which has some wear to extremities and small amount of chipping and a few minor tears.’ I misread the last word. It seemed like a very good description of Patricia Lindsay.