On 6th March 1947 Queen Mary opened the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition;it was the first since 1939 and there were queues in all directions.

For six years the home had been under threat. Husbands, fathers and sons had been away fighting, women had been conscripted into the forces or into factories, and thousands of children had been evacuated. Countless homes had been damaged or destroyed by enemy bombs. For the crowds who thronged the halls at Olympia in 1947 it must have been a kind of celebration of the fact that life was returning to something like normal.

Published in 1949, How to Run Your Home Without Help echoes that celebration. Many aspects of home life were still challenged by shortages. Death and divorce (60,250 in 1947, almost ten times as many as in 1938) had brought many marriages to an end. But for the vast majority of women the time had come to pick up new brooms. Four years earlier, 80% of married women had been working, either in the services or in industry. Of the 401,000 who married in 1947, close to 100% would have spent their teenage years as conscripts or directed workers. For the most part they welcomed the chance to stay at home, only too happy to swap the factory floor for the kitchen floor.

Although many more men returned from the Second World War than had returned from the first, the transition was better managed. Jobs were found, or created, for returning servicemen and ‘… two million – mostly married – women workers melted tactfully away when they began to feel unwelcome … ‘ (A Woman’s Place by Ruth Adam. Persephone Book No. 20). By 1947 only 18% of married women were in gainful employment. They would have a new role, which they were, more or less subtly, encouraged to embrace or re-embrace, that of housewife, exchanging their uniforms or drab factory overalls for the ‘crisp, easily removed gay overalls’ suggested by one exhibitor at the 1947 Ideal Home Exhibition, who added in his publicity material that ‘smocks, nylon or spongeable aprons look attractive. Wear your hair as you would do for the man of the house’s homecoming.’ He also included a work schedule that makes Kay Smallshaw’s read like a slacker’s charter. Homes would be provided for Heroes, and they would be run by heroines.

In Kitchen Essays (Persephone Book No. 30) Agnes Jekyll describes the courage and fortitude of women after the Great War, who had come down in the world but kept the spirit alive ‘by gallant and unswerving toil, sweeping the rooms and cooking the dinner, mothering the family and cheering the bread-winner … daily learning to solve the startling problems of house and kitchen … practising the making of drudgery divine.’ Lady Jekyll quotes from George Herbert’s poem ‘The Elixir’, a good Anglican hymn; Kay Smallshaw calls one of her chapters ‘The Daily Round’, a very frequent misquote (correctly, ‘the trivial round’) from John Keble’s nineteenth century hymn, ‘New Every Morning’. The message is the same: approached in the correct frame of mind, the common task brings us closer to God. No woman would be ‘just a housewife’. The angel would be back in the house once more.

Some women, released from war work, were returning to their pre-war life; others would have helped their mothers at the stove and the wash-tub; while some had never boiled a kettle or lifted a duster. A number of public bodies were there to help. The Electrical Association for Women and the Women’s Gas Council set up national networks of branches to teach women how to plan their kitchens, how best to use gas and electricity in their homes, and to provide in addition education on hygiene and social welfare. The Council for Industrial Design supplied information on, amongst other things, ‘How to Buy Furniture’ and ‘How to Buy Things for the Kitchen’. Guidance on diet and cooking continued to pour forth from the Ministry of Food. Practical advice on how to ‘make do and mend’ and make best use of food rations and clothing coupons – clothes rationing did not end until 1949, food rationing not until 1954 – was offered by women’s magazines like Woman and Good Housekeeping, where Kay Smallshaw was employed in the mid-1930s.

Her first book, How to Run Your Home Without Help, was aimed principally at the third group, the ‘newcomers’. Although she promises a time-table less exacting than those in older books on household management, her proposed régime strikes us now as pretty daunting. Perhaps it appeared less so to women accustomed over four years to clocking-in or turning up on parade, and was still driven by the vestiges of wartime spirit: ‘1-2 ½ hours for the daily tidying, 3-4 hours for shopping, cooking and washing-up, and 2-3 hours for house cleaning, washing and other big jobs’ – and that is just ‘a starting point’: between six and nine and a half hours a day, with additional time for weekly baking, patching, doing the flowers, keeping accounts and entertaining (entertaining!). Ruth Adam quotes a Mass Observation survey of 1947 recording that the stay-at-home housewife spent between 60 and 71 hours a week on the housework. Kay Smallshaw is not expecting anything out of the ordinary from her novice housewife.

In Charles Frazier’s American Civil War novel, Cold Mountain, one woman says of another that she ‘speaks only in verbs, all of them tiring’. That is the feeling one gets reading the contents page of How to Run Your Home Without Help, as we move (crawl) from Chapter 6 ‘The Daily Round’, to Chapter 7 ‘The Weekly Cleaning’, to Chapter 8 ‘More Weekly Cleaning’, to Chapter 9 ‘Spring Cleaning’. From time to time Kay Smallshaw timetables in a short break, but still to come are cooking and washing and mending, and ironing, which she indulgently suggests could be done sitting down.

As a new mother following Dr Spock, as we did then, I was advised by a friend to skip directly to ‘Managing with Twins’, in which Dr S. recommends the short-cuts that can be taken without endangering the health or well being of the infant. I like to think of the original reader of How to Run Your Home turning rapidly to Chapter 17 ‘Adapting the Routine When Baby Comes’, and heaving a great sigh of relief on being reassured that ‘weekly cleaning must certainly be cut down’, that ‘it won’t affect the comfort of the home if surrounds are polished much less often and furniture left to itself save for an occasional rub up with the duster’, that one can give up the net curtains, stop starching the table mats, send shirts to the laundry, stop ironing one’s husband’s underwear, and carry on wearing the maternity smock, which does so save one’s clothes. So much for cleanliness and godliness.

But, what a startling clear picture of late ‘40s middle class domestic life, from the placing of the cooker, and the refrigerator (if ‘you are lucky enough to have a refrigerator’), both gas and both moveable (how relaxing, but what would Health and Safety have to say?), to the need for a flap-table fixed to the larder door, ‘the only place where the wringer and the mincer can be screwed’. The kitchen, while it might not be one of ‘the streamlined masterpieces that meet our admiring gazes in the show-houses at exhibitions’, should enjoy ‘good light, air and enough sun or gaiety in decoration to give a lift to the spirits’ (features not considered essential before the war when the kitchen was the realm of servants). Washing powders and the ‘new liquid soap’ were beginning to replace hard soap and soda, but a washing machine, like a fridge, was a luxury, recommended nonetheless for the young mother (bought on the new Hire Purchase scheme). Mixers were just coming onto the market: the Kenwood Chef made its first appearance in 1947, though it would be a lot longer before the word ‘blitz’ became associated with it.

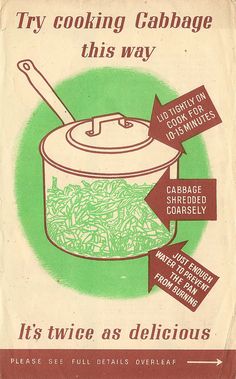

The menus and cooking tips, however, can make depressing reading – a three-layered steamer economically cooking a pudding, potatoes, and fish – and Kay Smallshaw does readily admit that ‘a meal that would be greeted with the warmest approval today would have been thought very ordinary before the war’. Never less than positive, however, she adds an encouraging corollary, ‘There are less materials on which to lavish culinary skill, and so less demands on the cook.’ [my italics]. The kitchen appliances may be museum pieces now, and the cleaning suggestions superseded or banned (DDT), but some of the tips cry out to be tested – silver boiled in an aluminium saucepan, fruit tested for setting in a solution of methylated spirits – and the advice on nutrition is exemplary and could hardly be bettered today. Oily fish, pulses instead of meat, National Bread rich in wheat germ, broccoli, citrus fruit, are all highly recommended, fats and sugar (strictly rationed in any case) warned against, ‘taken too generously they result in over-heaviness and sluggishness’.

What is utterly enchanting about How to Run Your Home is that it reads almost like a novel. Our young heroine is newly married to a husband sufficiently modern in outlook to be ready to lend a helping hand, stoking the boiler, washing up supper and preparing the weekend vegetables. He has willingly given up his study to provide a more convenient and better appointed kitchen for his new wife, and enjoys his ‘den’, the old kitchen, where he can store his tools and display his trophies, and when asked, service the vacuum cleaner. She makes friends with the shopkeepers who will then keep things aside for her, and might stop for tea or coffee out with baby in his pram (a remarkably well-behaved baby with improbably regular habits – it comes as no surprise to learn that Kay Smallshaw and her husband were childless). A friend might bring her mending over so that the two women can stitch away together. He has his friends in for a bridge four and she acts as hostess and kitchen maid. When she invites her friends, ‘he’ll rally round’. He might even cook at weekends, or bath the baby occasionally, but isn’t wholly reliable when it comes to housework, usually making ‘more work than her performs’. But the young couple have talked it all over. They entertain, a few friends perhaps to a ‘spaghetti supper’, with rough Algerian wine. Evenings in together are spent reading or listening to the wireless, while she knits or sews – more mending – and they both smoke contentedly, undisturbed by their sleeping baby. Before retiring, he will clean and re-lay the fire, while she plumps up the cushions and empties the ashtrays. And so to bed: the sheets may be sides to middled, but they will be tucked in with mitred hospital corners, the dusted ornaments will be prettily arranged on the skirted dressing table, the bath and basin wiped round after use.

So many Persephone Books come to mind reading How to Run Your Home: The Home-Maker (Persephone Book No.7), of course, The Carlyles at Home (Persephone Book No. 32) – I was reminded of Jane’s careful budgeting, Greenery Street (Persephone Book No, 35), except that they had two servants, and Felicity lunched most days with her parents – and many more, which leave unexplored the behind-the-scenes practicalities on which Kay Smallshaw’s short but detailed self-help book casts such a revealing light.