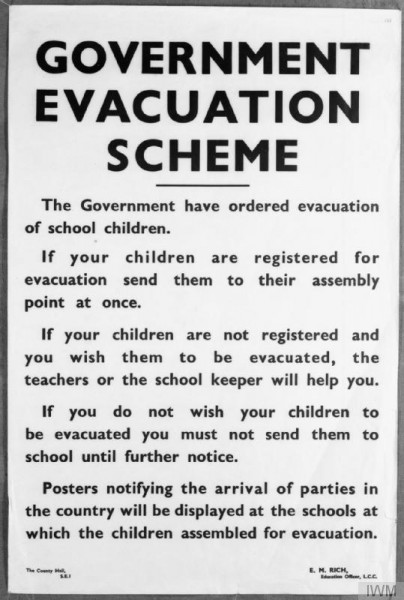

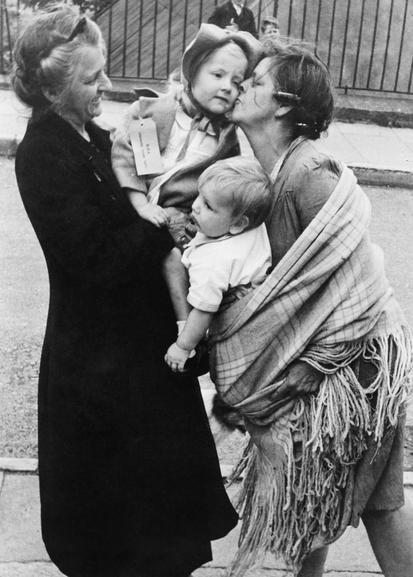

Pied Piper was the codename chosen for the mass evacuation of mothers and children which took place over the first four days of September 1939.

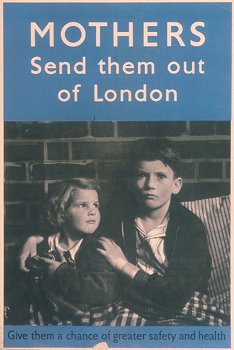

What lack of sensitivity, ignorance of the fate of the children of Hamelin, or cruelly prescient irony, lay behind the choice of such an unfortunate name, history does not relate. The man heading the operation was Sir John Anderson, better known for the shelters, which arguably saved more, and certainly damaged fewer lives than Pied Piper and subsequent, more limited, follow-up evacuation programmes. The scheme was voluntary, but throughout the first years of the war, and never more so than before the bombing had started, considerable pressure was put on city parents.

Teachers, 1.5 million schoolchildren, and mothers with small children were evacuated between 1st and 3rd September. By January 1940 sixty percent of these had returned home, almost all the mothers and a large number of the children. The threatened air raids had not materialised, the thirty-eight million gas-masks issued had lain unused in their cardboard boxes, and life in the countryside had not proved the promised idyll.

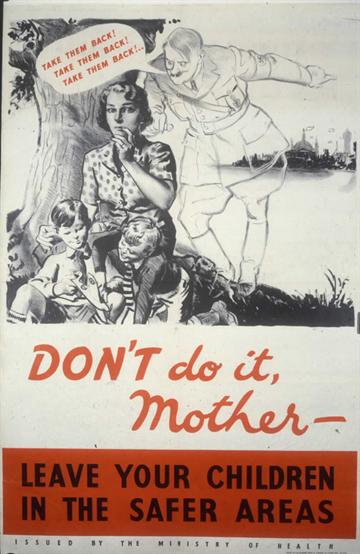

With the end of the Phoney War and the start of the blitz in September 1940 children were once more being evacuated, or re-evacuated, but in nothing like the same numbers. The wartime spirit that buoyed up the morale of the adults encouraged them to minimise the danger facing their children. Many families who had suffered the pain of separation once had no wish to repeat it, and others who had heard reports of wretchedly unhappy billets, and seen the despair of separated families preferred to face the dangers together rather than wave goodbye to their children.

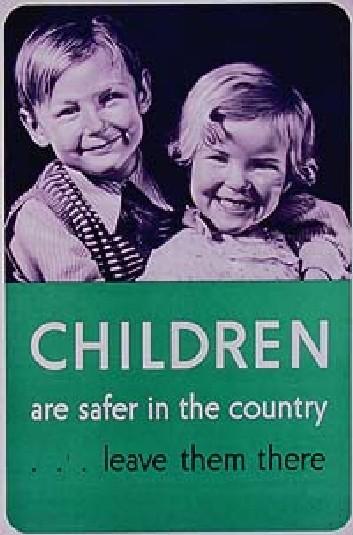

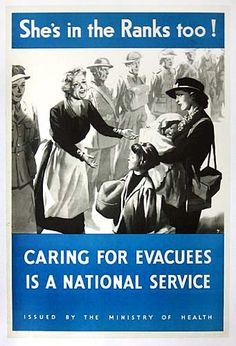

Poster propaganda continued to urge parents to send their children to safety in the countryside, and leave them there, but the decision, often taken by mothers on their own, was heart-breakingly difficult and liable to have lasting consequences. Writing at the end of the war, Barbara Noble may have been acquainted with John Bowlby’s early writings on the effect of maternal separation, as well as a survey published in 1942 by Dorothy Burlingham and Anna Freud, ‘The Child in Wartime’. ‘The war,’ it concludes, ‘acquires comparatively little significance for children so long as it only threatens their lives, disturbs their material comfort, or cuts their food rations. It becomes enormously significant the moment it breaks up family life and uproots the first emotional attachments of the child within the family group. London children therefore were on the whole much less upset by bombing than by evacuation as a protection against it.’ This was the very opposite of the message being propagated by the government.

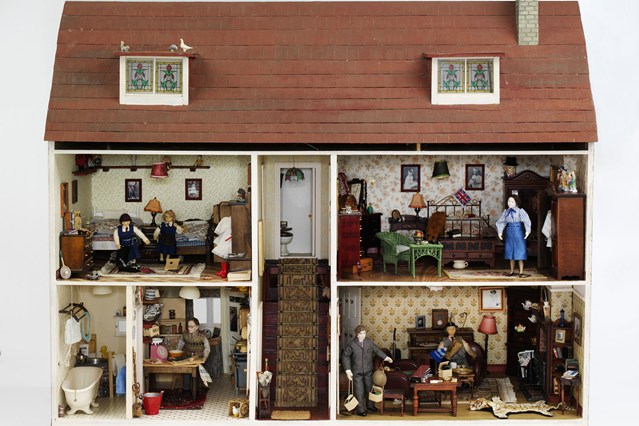

The year-long preparations for the evacuation programme had focused more on the immediate task of getting the children out of the cities, and finding accommodation for hundreds of thousands of them, than on any psychological problems that might be likely to arise, during or after their stay. Some harsh assumptions were made at the start of the war, mostly by upper middle-class men who had been sent away to boarding school at 7 or 8. To remove children not only from the danger of bombs, but, in many cases, from grim city slums and send them to a place of safety where they could run free in green fields and grow plump on fresh milk and home grown vegetables: what could possibly be wrong with that?

Writing in The New Yorker, Mollie Panter-Downes (even Mollie Panter-Downes!) blithely described ‘cheerful little cockneys who could hardly believe the luck that was sending them to the countryside’. Lucky for some, as it turned out, but not for all. And paradoxically for those who had the best luck and the best time, the unforeseen and unplanned-for pain of the return, the end of the dream childhood, combined with the problem of re-integrating into a splintered family, was as bad if not worse than the pain of departure, and intensified by feelings of guilt, baffling for a young child.

When the official history of the problems of social policy in the Second World War was published in 1950, Richard Titmuss observed: ‘From the first day of September 1939 evacuation ceased to be a problem of administrative planning. It became instead a multitude of problems in human relationships.’ In Doreen, which pre-dates the official history by four years, Barbara Noble analyses these very problems acutely and fairly, showing a real concern for the effects of evacuation on the child, on her mother (and to a lesser extent her father), and on her ‘foster-parents’.

‘You hear such tales … The truth is you don’t know what to do for the best,’ sighs Mrs Rawlings, shaken by the severity of the latest air-raid. Should she send Doreen to the country and risk losing her to strangers, or risk a worse loss by keeping her in London, where they live in two cramped attic rooms and she scrapes a meagre income working as an office cleaner? The offer of a private arrangement forces her decision. Mrs Rawlings will do the ‘right thing’: Doreen will go to the brother and sister-in-law of the office secretary. Helen Osborne is a worldly, unsentimental young woman, who makes the suggestion out of a sense of wartime duty, rather than any feeling for Mrs Rawlings, whom she finds obstinate and disagreeable. Geoffrey her older and equally unsentimental brother is a prosperous small town solicitor whose asthma has, to his dismay and shame, ruled him out of active service, and whose contributions to the war effort have to date been somewhat negative: not using his car, and not playing golf. Doreen will be his ‘war challenge’. He and his wife have no children, for which he blames himself (why?). Francie Osborne, desperate for a child of her own, will, in Mrs Rawling’s bitterly accurate words, reap the benefits of the bombs, and play her part in the war effort.

Towards the end of Doreen’s stay, Geoffrey looks back: ‘Not one of them, he reflected with dispassionate shame, had honestly put Doreen first. Yes, Mrs Rawlings had, in the beginning, when she consented to her leaving London, but she had not been able to sustain her sacrifice. Helen had intervened only to ease her conscience. Francie had welcomed not Doreen but the child whom she had never had. And he? He who had failed to give his wife a child, had smugly used another woman’s child as substitute. Poor Doreen, he thought bitterly; you deserved better of us than that.’ But, asks the novel, ‘could any of them have done better?’ Should Mrs Rawlings take her daughter back home, back to ‘the real world, the world outside the park railings’, a world of poverty and falling shrapnel, or leave her safe, living ‘soft’ with the Osbornes, whose love for Doreen she does not doubt, but which she fears? Doreen, presents an insoluble dilemma through very different characters. Helen and Geoffrey, both thoroughly likeable, rational beings hold the middle ground – but the fact is that there is no third option. The two extreme positions are held by Francie and Mrs Rawlings. Francie’s warmth makes her easier to like than Mrs Rawlings, but the dour, jealous Londoner is so subtly drawn that we find ourselves, albeit reluctantly, siding with her.

Mrs Rawlings is an obstinate woman, with ‘an angry confidence in her own invincible rightness’, a strong woman, who needs every ounce of strength to cope with the rigours of her daily life, and who despises the weakness which she, rightly, perceives in Francie. We know little of her history, beyond the fact that she has had limited education, and went into service, before seizing apparently the only chance of marriage that was likely to come her way – to a feckless, unfaithful drinker, who after a few years of noisy marital discord, left her to bring up Doreen on her own in miserably reduced circumstances. She has neighbours but no friends, keeping ‘herself to herself’, and forbidding Doreen from playing with other children; a gloomy soul, but honest with herself as far as she is able to be. Dully fatalistic – ‘It’s the luck of the game – some get too much and most get not enough. That’s how I see it’ – she aspires to no more for her daughter than she has herself. Grateful, insofar as she able to be, initially for the sanctuary offered to Doreen, later for the ‘nice way’ her daughter has learnt, she remains at war with the Osbornes who have ‘too much’, resolutely determined that they will not add Doreen to their possessions.

Would it have been better if Doreen had found herself billeted with a poorer family, a less welcoming one? Her father certainly thinks so. ‘You’d have done better to send her away to people in her own station, that’s what I mean.’ The Osbornes in his view are ‘too nice’. Have they spoiled her? Geoffrey has proved to be a bluff, genial, kindly ‘foster parent’, and Doreen finds him easy to relate to. He has taken pride in her progress, and been generous with his time and with presents, eager to share delights recalled from his own happy childhood. But he is aware that he feels less for her than his wife does, asking himself, and by implication us, ‘Was he abnormally detached or Francie abnormally involved.’ To which I think we would have to answer, ‘Both’.

Francie, whose childhood was ‘the most unhappy period of her life’, orphaned young, cared for, in a manner of speaking by older step-brothers and sisters, and sent away to school aged 7, recognises something of her young self in Doreen. She is determined to make her happy, to reclaim her own childhood. Her sensible friend gently suggests that it is possible to invest too much importance on happiness in childhood: children are ‘only the young of the species’. But Francie, lacking the foundation of a mother’s love, cannot see this, convinced that it’s better ‘for a child to be loved mistakenly than not at all’. What Francie forgets, or cannot acknowledge, is that Doreen is loved, by her own mother. Doreen is too young and lacks the words to explain to Francie what she feels when she finds herself back in the cramped, cluttered little home, ‘the atmosphere of absolute security that Mrs Rawlings radiated for her’, and Francie lacks the experience to understand it, or to appreciate why the little girl might find the Osbornes’ ‘scrupulous regard for her importance as an individual subtly more fatiguing that her mother’s downright yea and nay’.

Doreen would be too polite even to broach the subject. Somewhere along the way in her short life, she has developed ‘the instinct of preservation which bade her take on the protective colouring of her background’. She does not complain when her ‘new’ family address her as Doréen (stress on the second syllable), rather than Dóreen, nor it seems when Francie corrects her grammar, or rehearses with her the use of the correct knives and forks before taking her out to lunch. Helen Osborne, outspoken and clear-sighted, and far more intelligent than her sister-in-law, dares to remind her that Doreen is a visitor, that ‘She’ll go back to a world where most of the things you’ve taught her will be a drawback rather than an advantage.’ With greater detachment, and more articulately, she is saying the same as Mrs Rawlings, ‘She’s got to lead the life she was born to.’

Geoffrey too knows that ‘the happiness she brought them was a borrowed happiness’, and is sanguine about Doreen’s departure. He has seen the conditions to which she will be returning, two rooms in a tall London house which has known far better days, now ‘smeared … with the unmistakable tarnish of herd living’, but where ‘Mrs Rawlings – perhaps a host of Mrs Rawlings – aggressively maintained a quite considerable standard of honesty, cleanliness, manners and personal dignity.’ Francie is blind to her qualities, but Geoffrey, like Helen, find himself admiring Doreen’s mother. His brief contact with her has aroused a somnolent social conscience, made him question his upper middle-class attitudes towards those he refers to as ‘ordinary people’. Thanks to her he has learnt a lesson that he will not forgot when the war ends. He finds it a pity that she cannot share his pragmatism and agree that Doreen should be ‘entitled to have any good things that come her way’, but the child will be alright, so long as she is not killed.

The grown-ups all have views on Doreen’s future, on what they believe she might gain or lose by returning to her mother, but none, not even Helen, perceptive enough to know that it is for the good of Francie that the child be returned to London, none is able (or genuinely tries) to see it through Doreen’s eyes: ‘Dimly she perceived that what she was losing now was not just people whom she had loved and a way of living which had brought her happiness; she was losing her last opportunity to remain a child. The fact that her mother treated her as more of a child than the Osbornes did had, curiously nothing to do with it. Growing up was not conditioned by the time you went to bed. Growing up was finding out that grown-ups suffered.’ One way or another, Barbara Noble, reminds us, in this subtle and thought-provoking novel, war steals childhood.