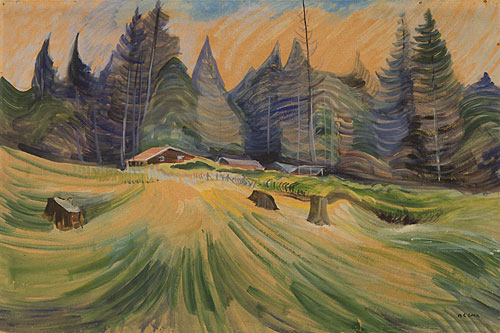

The arrival of someone as exotic as Mrs Dorval, with her furniture, her dog, and her mysterious but drab companion could not fail to excite curiosity in Lytton, a small community in British Columbia, at the confluence of two major rivers and surrounded by forest and mountain. Hetty Dorval, we learn, has arrived, indirectly, from Shanghai, and her reputation, if it hasn’t gone before her, has followed very close behind. Hetty it seems is a Menace. Her power lies in her beauty, another force of nature, ‘the potent and insinuating quality of line, be it in a mountain, or in a tree, or in human face’.

‘She was all that I thought beautiful, and so nice to be with. That I believe was Hetty’s chief equipment for life. She was beautiful and so nice to be with.’ In three short sentences, and repeating the same words with only an implied change in intonation, Ethel Wilson shifts from the voice of a child to that of an adult, from innocent admiration, to quiet contempt. Hetty Dorval was the first of Ethel Wilson’s novels to be published. She was 59 yet in this almost perfect novella speaks utterly convincingly with the voice first of a twelve-year-old, then of a young woman, the two interwoven almost imperceptibly with that of a much older, and much wiser narrator. Ethel Wilson does not specify how much older, but strongly suggests that Frances Burnaby is writing at some remove from the events she is describing, from her first encounter as the child Frankie with the beautiful enchantress Hetty Dorval to their parting seven years later. There is much to suggest that this is not a final parting.

‘

Frankie is a sensible child, well-grounded, happy. Her farming parents are intelligent, adequately prosperous and quietly loving of her and of each other: ‘life for me could not have been bettered.’ Nothing marks her out as vulnerable, nor when they meet on the road to Lytton and share their delight in the flight of geese, is there anything threatening about Hetty, other than her shockingly casual exclamation, “God”. The child Frankie observes that Hetty is different, ‘she rode on one of those small English saddles – which other people didn’t – and sat erect but easy’. How telling Wilson’s dashes are! She hears something in her voice, in her language that is unfamiliar: the people Frankie knows don’t refer to things as ‘too divine’.

Later, more surprised than shocked at being made to promise to keep secret her visits to the bungalow Hetty shares with her companion-housekeeper, Mouse, young Frankie is ‘unsentimental enough to realise that there was something silly and unreasonable in her exacting such a promise’, but it is years before she appreciates that it was more than silly, that Hetty Dorval was gently propelling her into ‘an existence that was not normal for a child’. The child is ignorant of grown-up wiles. The Burnabys are good, straightforward people, how can she perceive, on her first visit, the hypocrisy behind Hetty’s gushingly dismissive treatment of the church minister? Only later does the mature Frankie look back and recognise the use of that ‘weapon of lightness’, which will become so familiar, and, belatedly, understand Mouse’s words, ‘keeping your hand in, I see, Hester.’ There is a history there. Frankie, we must understand, is not the first to fall under the Dorval ‘spell of beauty’.

The narrator is sympathetic to her younger self: ‘It could not be expected of a child of twelve that she should recognise in the space of an afternoon the complete self-indulgence and idleness of a new and charming friend…’ If there is blame to be apportioned it is to Hetty that it must be directed, and she continues, ‘there is no question now about the self-indulgence and idleness of Hetty’ – the italics are mine. It is unclear exactly when ‘now’ is, how many years have passed, but if it is clear from what Mouse says that if there was a pattern to Hetty’s behaviour before she came to Lytton, the ‘now’ confirms that it continued after she left. Hetty will take more scalps as time goes on, take them not out of cruelty, nor even deliberately, more in the manner of a dilettante and impulsive collector, gathering and shedding objects , enjoying them for a while, and wiping them from her mind when they cease to please: except that in her case the objects are people.

Hetty has the power to change other peoples’ lives, but is not changed by them. Events do not mould her. The past means nothing to her. She has the power to enthral, but ‘if any person or thing threatened her comfort or her desires, then that person or thing no longer existed as far as she was concerned.’ Hetty Dorval is careless, lacking in care, not cruel, but a Menace to those who find themselves caught in the slipstream of her charms. She considers herself to be no more responsible for their effect than the sullen, opaque Fraser river is ‘responsible’ for overcoming the dancing, blue-green waters of its tributary Thompson river.

She is impervious to guilt, the truth is what she says it is. Her narrative is unreliable, not deliberately obfuscated, simply unreliable. Frankie’s parents are right, Hetty is a Menace, but the damage she does is not intentional, because she has no intention beyond preserving her own security. She is herself damaged, although we (and she) do not discover this until late in the novel (no spoiler), and she will, we sense, wipe even that discovery from the slate.

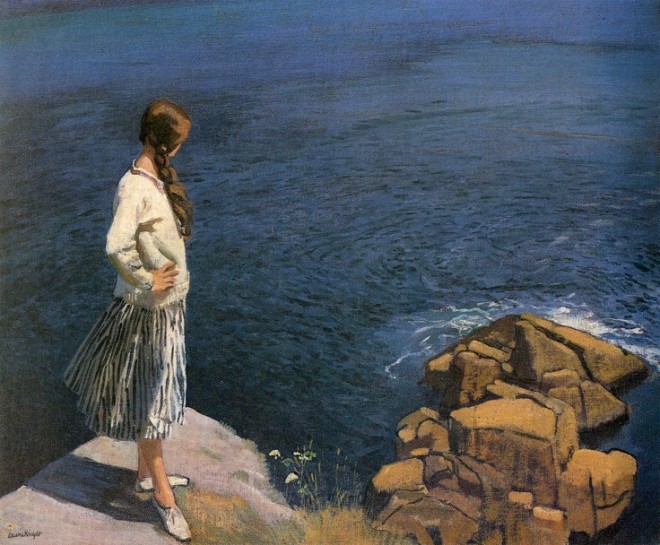

If Hetty is defined by her immutability, Frankie matures: the impressionable child, grows into a sensitive, strong, honest, outgoing, independent young woman, with a profound sense of responsibility. Everything that Hetty is not. Hetty Dorval is as much Frankie’s story as it is Hetty’s (Northrop Frye makes a strong case for this in his Afterword). Hetty is one catalyst in her life, but there are other defining moments, which have nothing, or little, to do with the eponymous anti-heroine. Frankie’s mother who has ‘a good working knowledge of human beings’ carefully guides her out of the crisis of the first encounter, and ensures that she does not turn into the predictable victim. She goes away to school, where, unlike many more conventional literary figures, she is well taught, blissfully happy and surrounded by a cheerful circle of friends – so much so that she is able to turn away from Hetty when she spots her in a Vancouver jewellery store. She encounters death for the first time: her close friend Ernestine is drowned, a death foreseen in the first chapter – incidentally the first clear marker for the reader that this is not a linear narrative. She leaves for Europe and discovers the pain and the excitement of departure, followed by the thrill of the ocean voyage and the intensity of shipboard life with its rapidly formed community, that ‘small mobile aristocracy’. She thrills to the coast of Cornwall and to her newly extended family. Her growing up is rich with experience, with love, loss, pain, all of which leave their mark, and which form her character.

Ethel Wilson writes about childhood with clarity and unsentimental innocence, casually appending the most significant details, as children do. Even in her adult voice, her sentences are short, with barely a subordinate clause, nor a superfluous adjective. She pairs words like a poet, so that each is enriched: surrounding solitudes, exacting loneliness, immoderate mountains; and makes play with language: the unconventionality of Hetty’s endeavour ‘to island herself in her own particular world of comfort and irresponsibility’ is heightened by her appropriation of a noun as a verb.

This is a brilliant and disturbing novella, which plays both with Time and with Truth, in which not a word is wasted. A childhood infatuation turns almost imperceptibly into a battle between two adult women, in which moral strength is almost but not quite equal to the potency of beauty. ‘Although I had fought her and driven her off, and would fight her again if I had to and defeat her, too, she was hard to hate as I looked at her.’ We are left speculating as to the potency of history.