‘In the years to come, children will be taught about ghettos and yellow stars and the terror at school and it will make their hair stand on end…. But parallel with that textbook history, there also runs another… It is probably worth quite a bit being personally involved in the writing of history. You can really tell then what the history books leave out.’ Thursday, six o’clock, April 1942.

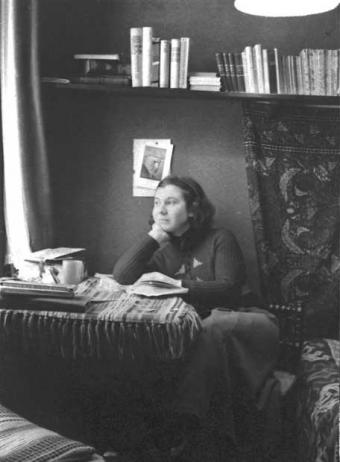

Etty wrote her diaries and letters in Amsterdam and in the transit camp at Westerbork in the east of the Netherlands over a two year period. She was 29 when she died at Auschwitz on 30 November 1943. During the period she was writing, the lives of the Jewish inhabitants of Amsterdam were becoming ever more restricted and round-ups and deportations began. The later diary entries and the letters describe life at Westerbork, where Etty was interned before being deported to Poland.

Etty’s diaries are extraordinary because, though she remains engaged with what is happening around her, she is also finding her own path towards what Eva Hoffman in the Preface calls ‘a perfect inward pitch’, to a place where she feels ‘the hidden harmony of the world’. So her writings – though they document the suffering and sorrow leading up to the tragic end of her own life and the lives of many, many others – also contain beauty, warmth and joy.

The early diary entries chronicle the beginnings of Etty’s relationship with Julius Spier, a charismatic figure with a Jungian psychoanalytical training who founded psychochirology (reading people’s lives and characters from their palms). Etty relates the questionable physical methods of instruction he used with his devoted followers – including herself – which were supposedly intended to demonstrate that the body and soul are one. She embarks on a relationship with him which is a catalyst for the development of her remarkable ‘inward pitch’ – call it spirituality or religion if you will, though arguably it resists any definitive categorisation.

Other people feature in Etty’s diary entries: her co-habitants in a house overlooking the Museumplein in Amsterdam, including Han, the owner of the house, with whom she also has a relationship. Then there are other friends and figures from Amsterdam’s academic and artistic circles and her family: her mother, her scholarly Headmaster father and her two brothers, Mischa, a talented pianist and Jaap, a doctor.

Etty studied Law, Psychology and Russian at university. Her aspiration is to write but, to earn money, she teaches Russian to private pupils. Later she is given a job at the Jewish Council as typist, though at every opportunity she escapes to a quiet corner to read. She reads a great deal, particularly Rilke and Dostoyevsky. The Old Testament, Jung, Kropotkin, St Augustine’s letters and an number of other works are also mentioned in her diaries.

Etty kept a diary for a number of reasons. She wrote for herself. She wanted it to be a place from which she could create a continuous thread running through her days, a thread that ‘is really one’s life’. Reading sections of it over to herself gave her strength. At one point, she suggests that she would like to have something to remind her of who she had once been if she survived the camps.

She also aspires to be one of the ‘chroniclers’ of her age. She records events and the suffering of people around her: the measures taken against Jews in Amsterdam; her work and her colleagues at the Jewish Council; life at Westerbork; the weekly transports. Two of her longer letters about Westerbork (the ones dated 18 December 1942 and 24 August 1943) were published by the Dutch Resistance in 1943.

But she is very clear that ‘little journalistic pieces’ that ‘simply record the bare facts’ will not suffice, nor does she see herself as suited to ‘describing a specific place or events’. The appropriate form she suggests is poetry, or even fairy tales because the misery ‘is so beyond all bounds of reality that it has become completely unreal’. Even in her earlier diary entries, she is clear that her focus is not on events, on what happens and on what is said. Her writing is alive with vivid daily-life moments in which she experiences the beauty and meaningfulness of life.

She wrote ‘so that others don’t have to start from scratch’. In a letter dated 18 December 1942, she writes: ‘if we have nothing to offer a desolate post-war world but our bodies saved at any cost, if we fail to draw new meaning from the deep wells of our distress and despair, then it will not be enough. New thoughts will have to radiate outwards from the camps themselves, new insights, spreading lucidity, will have to cross the barbed wire enclosing us’. She wanted to share what she had learned about living with others.

For she had learned a great deal. The book merits reading (and re-reading) by almost anyone for this reason alone. It is impossible to convey here the richness of her perspective on life as it develops through her writing and as she lived it. Towards the end, she recognises ways in which her approach might be misinterpreted. She writes of her dislike for the sort of ‘you must try to make the best of things’ or ‘seeing the good in everything’ type of attitude. She isn’t a precursor to the sort of faith in the transformative powers of positive thinking that abounds in contemporary popular psychology, self-help or (many but not all) spiritually-orientated works. Nor does she sit easily within any particular religious tradition, though she does pray and she alludes to God repeatedly and specifically mentions Christianity. But the power of her writing in part comes from the sense the reader has that the perspective she is forming is very much her own.

Her perspective is not only an internal attitude: it is also a lived reality. Increasingly, she is able to shift her focus from her current situation, and even from the suffering of her people, and to view it in the context of history, and indeed, of eternity. She is aware that her life has tended towards intellectual study and contemplation, and that she isn’t going to have an impact in the world by becoming ‘a social-worker or a political reformer’, but she feels that her life has nevertheless prepared her well for the camps where she seeks to be ‘a balm for all wounds’.

She remains vitally engaged with life whilst also letting go ‘grasping attachments’ – to the material comforts of her Amsterdam life; to people she loves and even to trying to preserve her own life (hence her refusal to go into hiding).

She writes of compassion and love for ‘everyone with whom one happens to share one’s life’. Though she is horrified and sickened by what she sees at Westerbork and writes of her deep moral indignation, her compassion leaves no room for hatred, even hatred of her German persecutors.

She has an extraordinary ability to allow sorrow the space it demands and yet to perceive beauty and joy in the everyday world and to be thankful for this, even as that world becomes ever darker, ever more lacking in external sources of life and joy. In her Amsterdam entries she marvels at the beauty of the jasmine growing outside her bedroom window. At Westerbork, she describes fields of lupins, the reflections sunshine in muddy puddles. The camp itself, on a moonlit night, to her seems to be ‘made out of silver and eternity’.

Her writing is full of beauty and truth and resists categorisation in any conventional way, or any kind definitive analysis. Indeed it at times seems to resist words themselves.

One Friday in May 1942, she writes: ‘Looked at Japanese prints with Glassner this afternoon. That’s how I want to write. With that much space surrounding the words. They would simply emphasise the silence. Just like that print with the sprig of blossom in the lower corner. A few delicate brush strokes – but with what attention to the smallest detail – and all around it space, not empty but inspired. The few great things that matter in life can be said in a few words. If I should ever write – but what? – I would like to brush in a few words against a wordless background. To describe the silence and stillness and to inspire them. What matters is the right relationship between words and wordlessness, the wordlessness in which much more happens that in all the words that one can string together’.

Questions

How does Etty’s writing compare with that of others who left a record of their lives and thought during these years (most obviously, Anne Frank but there are numerous others, for example, Charlotte Salomon, Edith Stein and Simone Weil)

‘Its not at all simple, the role of women’. What do Etty’s 1941 diary entries (particularly in June, August and October 1941) have to say on this subject? How is this reflected in her evolving relationship with Julius Spier.

‘I no longer believe that we can change anything in the world until we have first changed ourselves.’ 19 February 1942. What do you think of Etty’s chosen path of resistance to what is happening in the world around her?

10 replies on “Persephone Book No 5: An Interrupted Life: The Diaries and Letters of Etty Hillesum 1941-1943”

It is an astonishing book and well worth the effort of tracking down.

That said, I have to admit that I found the diaries hard to get through at first because of Etty’s seeming self-obsession and the uncomfortable voyeurism I felt at reading of her wrestling matches with the opportunistic Speir. I felt sure that the letters would be worth the effort of sticking with the diaries and reminded myself that Etty was a young woman finding herself and not writing for publication, so how else would she seem but self-obesessed? And it wasn’t in a bad way . . . . And how those letters are worth the hanging-in!

It’s hard to think that she was writing the diaries and the letters without any conscious effort at creating anything other than a written record. Not unlike the authors of ‘William: An Englishman’ or ‘Mariana’, Etty reports in her diaries the insidious growth of Gestapo activity, from comparatively minor annoyance of restricted access to parts of the town to the shock of disappearances of friends. Etty is not imposing structure on a novel but is telling it like it is.

In her letters she shows us unwittingly the growth of her intelligence and generosity of spirit. I was also impressed by her admission that ‘if we have nothing to offer a desolate post-war world but our bodies saved at any cost, if we fail to draw new meaning from the deep wells of our distress and despair, then it will not be enough.’ She learned to write very poetically, but without whimsy. Of many examples, 2 stand out for me: ‘ From my bunk I can see gulls in the distance moving acrossthe flat grey sky. They are like free thoughts in an open mind.’ And her description of a little hunchbacked Russian woman who ‘stands there as if spun as in a web of sorrow.’ Did she but know it, she had learned ‘to brush in a few words against a wordless background.’

We are so sorry that An Interrupted Life is reprinting at the precise moment the Forum has gone live about the book – very bad timing but just one of those things. However, Persephone have found five copies in the office at the Lambs Conduit Street shop (so do email info@persephonebooks.co.uk if you want one). Plenty of copies are also available from the following sites:

Amazon have 9 copies of the Persephone edition and many more copies of other English language editions: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Interrupted-Life-Diaries-Letters-Hillesum/dp/095347805X/ref=sr_1_2?s=gateway&ie=UTF8&qid=1285946534&sr=8-2

Abe Books also have numerous copies, including 6 copies of the Persephone edition:

http://www.abebooks.co.uk/servlet/SearchResults?an=etty+hillesum&bt.x=0&bt.y=0&sts=t

Having lived in Warsaw as an expat spouse I spent much time learning about the horrors of the second world war and reading a lot of survivor memoirs about the death camps.

This is the first one that I found so utterly heartbreaking that I was unable to finish it. I suppose that must be testimony to the beauty of the writing as you really felt you were living it with them. The transit camp Westerbork (where Anne Frank also spent time) was conveyed in harrowing detail and the utter misery of life there.

Too much for me- maybe I will retry at some point in the future.

I really enjoyed ‘Manja’- a great novel about the same period of history.

I read Etty Hillesum’s book over ten years ago, a copy given to me by my mother, and found it one of the most moving books I’ve ever read. It is agonizing in its sadness and in knowing what is to happen to Etty, but there is also something beautiful and hopeful and miraculous about it.

The description mentioned above – ‘A guard with an enraptured expression is picking purple lupins, his gun dangling on his back’ clearly represents her style – she writes in pictures, often very simple and direct, that lodge in the memory. Another picture has stayed in my mind, and often returns to me, of monks, in habits, I think at the Westerbork camp, who prayed using their rosaries hanging at their belts, oases of serenity.

Often, despite the terrible times she was living through, Etty described the world as though it was glowing, bathed in a spiritual light. But she was also down to earth, and straight forward, forensically honest about her feelings.

‘An Interrupted Life’ is the journal of a mystic who lived through horror and yet who looked at the world transformed through a prism of love.

I struggled to read this book. My first struggle was with the tedium of the diary pages. My second was with tears of emotion over the letters pages.

I am very glad I persevered with this book. I did find the diary pages hard going but know that if a book’s in the Persephone stable, then it must have merit and be worth my while. Bits of the diary left me wanting to know more – about her mother and Etty’s reaction to being back at home, and especially about that wrestling lark! The letters were clever in their lack of detail. Etty told just enough and as we have the (sad) benefit of knowledge, we can fill in the blanks. The diary had already shown how Etty thought, how she managed her inner conflicts and how her belief in God helped her and guided her. Even so, how did she manage not to whinge and moan? Stoic is not the right word. She seemed to be able to rise above the situation, no doubt also aided by having a function at the camp as a rep of the Jewish Council.

One point I found really startling was that it wasn’t even obvious to me that Etty was Jewish! Religious, yes, but not specifically Jewish. Just a young woman. As always, man’s inhumanity to man is unfathomable. How can one country allow itself to be invaded by the army of another and then watch as that army persecutes a sub-set of its citizens? How can that invading army think it has the right? May I never find out.

Various ‘dramas’ and inconveniences have been going on in my own life while I’ve been reading An Interrupted Life but the thought of the book hovers over me constantly and makes me feel stupid for getting het up about such petty, inconsequential things.

Must agree with Gina on this one. Perhaps another time I can read it with less emotion.

D. Ellis

Just thought you might like to know that a friend of mine who lives in Leeds has informed me that her local book group has chosen Etty’s diaty & letters for their November read. Not sure if there’s any connection with Persephone, but it will be interesting to find out what they think after their next meeting . . . .

Yesterday I watched a programme I’d taped from the week before – a BBC2 Wonderland film entitled ‘The British in Bed’. One of the couples mentioned were elderly, Jewish, and from Holland originally; no surprise then, that the wife had spent some time at Westerbork, and was still buying three times as much bread as she needed to compensate for the deprivations of her childhood.

I am looking for the November 21, 1941 (that Etty wrote) entry for a translation from Spanish to English. Could you please post it or e-mail it to me as soon as possible?

Thank you! Claudia

When I read Etty I find myself also full of emotion. It can take a day to read just of few pages for all the thoughts her insights raise and which my mind then contemplates. However, ‘An Interrupted life’ is only an edited version of the full letters and diary’s whcih, called ‘Etty’, can be picked up for about £60 on the internet second hand. It is 800 pages and contains extensive notes from the editor. For me, this gives a much richer account and a deeper understanding of Etty than the shorter An Interrupted Life. There has also just been published by Brill an anthology of scholarly articles on Etty called, ‘The Spirituality of Etty Hillesum.’

We are only just beginning to leran about Etty in Britian. What she provides is a reason for and a praxis of hope in troubled times and a personal spirituality that is re-freshingly liberal, open and explorative in an age fundamentalist certainties.

I would recommend eveyone to have a read of Etty whatever edition.

Philip Knight