A new phrase entered the vocabulary of human relationships recently : ‘conscious uncoupling’. Thanks to Gwyneth Paltrow and her rock star husband we have learned that this is a ‘proven process for lovingly completing a relationship’. For ‘completing’, we must read ‘ending’, and ‘proven’ … who knows? In any case congratulations seem to be in order, for by celeb standards Gwyneth and Chris achieved something of a record: together for ten years

For Martin and Letty Lovell in Bricks and Mortar, the tenth year of marriage was marked by the arrival of a third child, a son, stillborn, and the realisation for Martin that ‘some vital current had ceased to flow between them …. He was left with a sense of strange irreparable loss: the dear, dull, familiar woman who now shared his domestic life was not the Letty he had married; his heart ached for the loss of that bright foolish creature.’ Her life had become centred on her children, and although she remained gentle and tender towards him, ‘some vital current had ceased to flow between them.’ Today’s relationship guru would definitely be calling ‘time’. Not in 1903. In the first decade of the last century only one in four-hundred-and-fifty marriages in the UK ended in divorce. According to Ruth Adam in A Woman’s Place (Persephone Book No. 20), between 1911 and 1915 there were 3,100 divorces, fewer than eight hundred a year. In 2012 there were thirteen divorces an hour in England and Wales. Marriage in 1903 didn’t end with the dream, if indeed it had started with the dream.

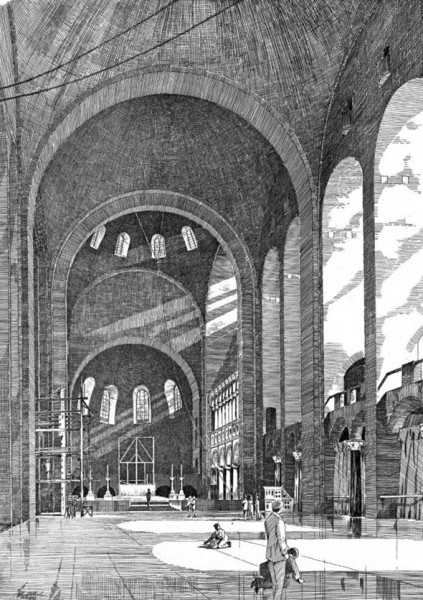

Bricks and Mortar opens in 1892 in Rome. Martin Lovell is 24, a budding architect, ‘a very decent, simple, sweet-minded creature’, earnest and ambitious, but easily swept off his feet by eighteen-year-old Letty Stapleford, with forget-me-not eyes, smooth golden hair and an impoverished widowed mother, ruthlessly determined to see her married as soon, and as economically, as possible. Martin’s prospects are adequate, his antecedents are acceptable and Lady Stapleford has no trouble convincing him that he is truly in love with her daughter. Letty’s reluctance, unknown to Martin, is, shockingly, overcome by ‘a good slapping and shaking.’ And so the young architect leaves Rome with a frightened young bride, and a hundred regrets for all the unseen churches, and temples and monuments. Persephone readers are often reminded how important it was, as late as the 1930s, for a young woman, particularly one with no money of her own, to find a husband. Our hearts have gone out these girls, but Helen Ashton opens our eyes to the plight of the young men. Martin is not a weak man, but he is no match for a martinet in search of a son-in-law.

Letty quickly proves to be in many ways a disappointment: ‘uneducated, ignorant, vain, weakly impressionable, and yet firm in her tiny prejudices, dependent, stupid and easily hurt’, but harsh as his assessment appears, Martin does not stop loving her. The author’s voice is principally his voice, so we can only surmise what Letty feels – something short of passion, a sort of benign acceptance perhaps, deepening over the years. She cannot be faulted as far as tolerance goes: although she never shows much interest or understanding of his work, or shares any of his delight in fine buildings, she indulges his need for occasional breaks from family life, and selflessly puts up with seven moves in thirty years, all to satisfy Martin’s fascination with restoration and refurbishment – if she does complain, the reader is not told. Martin never fulfils his youthful dream of building his own house. Are we to believe that he is prevented from doing so by Letty? Is it not rather that the building of marriage and family is a hard enough task in itself? Hard and with all the compromises and frustrations of working with bricks and mortar: the dream is never quite realised, spaces are enclosed, openings let in less light than planned. Life and architecture intertwine. ‘He was to discover later that he always liked a house best when the walls had only risen three or four feet between the scaffold-poles; when the doors and window frames were still empty … A building was somehow more amusing and promising then that in the later stages when the floor-boards were being hammered down on the joists, when the blind glass panes with their circles of whitewash shut out the view, and the roof was being closed in, and all the rooms looked dark and small and somehow not as pleasant as he had expected.’ Just like his marriage.

The young Lovells first proper home together, a ‘six-roomed cottage’ in Hampstead, with their two small children, a sturdy little daughter adored by her father, and a sickly son doted on by his mother, offers the promise of happiness. Martin can draw in his light filled attic, and Letty can sew and push the children out in their pram; ‘very simple and unexciting and pleasant’, and unfulfilling. Allowed no say in the choice, furnishing or decoration of this house (or subsequent ones) Letty has continued to seek a sort of harsh comfort from her mother: little wonder then that she has been ‘very little developed by six years of marriage’. For his part Martin has come to believe that ‘the chief variety and excitement of his future life would lie in his profession and outside his own house’ – a belief that he would continue to hold, and, unkindly, profess many years later to his daughter. ‘They had,’ reflects Martin, ‘learnt each other’s limitations.’ But their life together would continue, just as his architectural career, while never reaching the dizzy heights to which he had aspired in his twenties, continues. ‘Letty was still the only woman in his heart, he never loved any other; but his deepest interest was in his work.’ And thus it will remain.

If Helen Ashton is intrigued by the notion of architecture as a metaphor for life, she is equally if not more intrigued by architecture as architecture, and the four architects in Bricks and Mortar (Martin’s boss and early mentor, Nicholas Barford, Martin himself, Oliver, Nick’s nephew and Stacy, Martin’s daughter), provide a sweep through seventy-five years of building in England, from Pugin and Sir Gilbert Scott, to Webb, Norman Shaw, and the followers of Corbusier. Each has his or her heroes, loves and hates. Fashions change, the new ceases to shock, the old finds fresh admirers. Past styles go in and out of favour: for Nicholas Barford, the head of the practice, in his fifties, there is nothing to beat the Gothic, Martin leans towards the Classical, and his daughter enthuses about the Baroque. Ashton is thrilled by the detail of it all. Martin’s travels through Europe, solitary at first, and later with his daughter Stacy, produce lingering descriptions of Venice, and Rome and Brussels and Ghent and Provence. As exciting and instructive are her on-the-spot accounts of the construction of buildings which are now such integral parts of the London cityscape that it is impossible to believe that they were once nothing more than a mass of scaffolding and plans on paper, and that, when they were first built, could have generated such outrage. ‘… that railway station with the Roman candle that Bentley has stuck up for the RCs’, Westminster Cathedral, ‘the prow of a bulk as arrogant as a battleship’, Broadcasting House, Adelaide House.

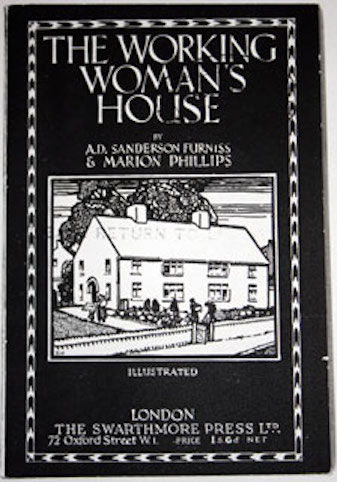

These are bold structures, monumental expressions of the dreams of ambitious architects, mostly young and, in Asthon’s lifetime, male. The men in Bricks and Mortar want to build big, but with age are compelled to lower their sights. Having started with Gothic revival town halls, Nicholas Barford subsequently found a niche in vicarages, and in his latter days is reduced to extensions of his early designs. Martin downsizes from large country houses for rich clients to copies of ‘an olde Englishe cottage from the Ideal Home Exhibition, or a sweet little Queen Anne House that their uncle’s widow had just built at Purley.’ We leave Oliver, still only in his thirties, designing factories and banks and flats and yearning for a skyline more like that of New York. Stacy Lovell has no such soaring ambition. Neither her father, nor her husband, nor Ashton herself, question the fact that she should be designing nothing more than ‘compact manageable little houses in the suburbs’.

The house must be ‘manageable’, because this is a servantless post-war era. It is the 1920s, Stacy is a ‘new woman’, part of a generation of single women, unmarried or widowed, ‘going valiantly about together in threes and fours, calling each other heartily by their surnames.’ Her achievement has been to qualify as an architect, and later to combine family and work – Ashton, herself, had given up a career as a doctor when she married (her character’s medical conditions are described in clinical detail!).

Not a long novel, Bricks and Mortar is a very rich one, deftly, and often wittily, wrapping together lyrical descriptions of country life, the joys, difficulties and sorrows of parenting, architectural practice and history, and a subtle account of a complex and enduring marriage. ‘He and Letty had come to love each other in the end with all their hearts … They had eaten their portion of disappointment together, and they had shared one great sorrow, they had become indivisible.’ Perhaps that kind of marriage is history too.