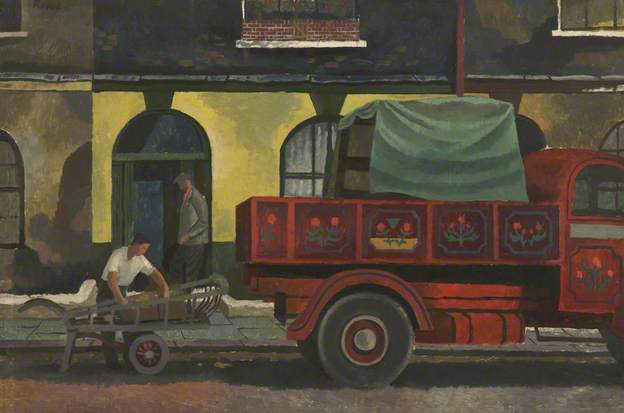

Looking round the bedroom that had been hers, now empty of furniture, Rhoda reflects that ‘she had borrowed the room from the house and given it back to it. The house had received it again, taking no notice of her. She stood there, a stranger.’ The old house is no longer home, and the new house has yet to become home. The familiar furniture, the cherished ornaments, the linen, the pictures, the mementos, have been packed and stacked in vans, a sort of limbo, awaiting re-incarnation within different walls. It is a period between two ‘normalities’ and Rhoda Powell finds herself enjoying an unexpected sense of freedom, as if a rope that tethered her had been cut. The prospect of new things and possible adventure opens up before her: new house, new life.

The New House opens with Rhoda’s waking in one bedroom and ends with her falling asleep in another. Surprised by the lack of drama attendant on the leaving of Stone Hall, the family home of thirty years, ‘just as if you were going for a drive in the morning and coming back for lunch’, she is nonetheless keenly aware of the importance of the day, ‘like a crack in my life. Things are coming up through the crack, and, if I don’t look at them, perhaps I shall never see them again. Ordinary life in the new house will begin tomorrow and grow over the crack and seal it up.’ Less of a physical wrench than she had expected, moving day, or ‘removing day’ as it was known in the thirties, generates a powerful psychological force, bringing to the surface memories and feelings, and providing a moment to pause and reflect on them. Rhoda is not alone: other members of the family, gathered to help with the move, find themselves similarly thinking about the past, the future, the possibility, or impossibility of change for themselves, and for the wider world.

A convinced socialist and an equally convinced Freudian, Lettice Cooper deftly (and unexpectedly humorously at times) weaves the message of the need for social change with the belief that patterns of adult behaviour are (almost) immutably determined in childhood, a belief which makes her interestingly quite forgiving of some of the worst traits of her least attractive characters. Rhoda’s mother, Natalie Powell, is bad, but not all bad, ‘busy, exacting, sometimes tender’; her late father, she remembers as ‘laughing and playing’: clearly the more attractive parent, but unable to protect her (or himself) from his self-centred and demanding wife (not her fault – her mother was like that). Indulged by her mother, spoilt by her older sister, consistently given in to by her husband, she, Natalie, has an exaggerated but rarely challenged sense of entitlement, ‘the potency of someone who never questioned the absolute rightness of her own wishes’. It seems rather harsh to blame those around her, but there must be some truth in Lettice Cooper’s assessment that unselfish people make selfish ones. In an eye-opening moment, watching her mother defeated in argument by her sister’s outspoken fiancé (a refreshing voice from outside the family), Rhoda recognises that ‘tyranny is not all the tyrant’s fault.’ She acknowledges that she, her father and her brother have all yielded too readily. What she never quite acknowledges, although Lettice Cooper makes it clear, is the extent to which she has used her mother’s manipulative neediness as a crutch: a timid child, a nervous schoolgirl, an unadventurous twenty-year old – it has been easy to conceal her lack of courage under the guise first of the obedient, later of the dutiful daughter. Fearing both her mother’s rage and her tears, for Natalie had always got her way ‘by being either angry or crying’, Rhoda has remained at home, letting life and love slip by, so that at thirty-three she feels old: ‘It’s not old if you done things before you get there’, she says to her sister, ‘but it is if you haven’t.’

Maurice, the home-loving, equally dutiful son, cast in the same mould as his gentle father, has found the courage to leave, because that is what men do, but has married a woman who is (although neither the arriviste Surrey girl, Evelyn, nor her snobbish mother-in-law would admit this) in many ways like his own mother. The sale of Stone Hall, which he has continued to think of, and, to his wife’s understandable irritation, refer to as ‘home’, long after their marriage, forces him to face up to life not as a son, but as a husband. The house he shares with Evelyn and their daughter must now become home. He had thought himself more fortunate than Rhoda, having both his work and his family, while she had ‘nothing of her own to which she was necessary’, but making money and maintaining moral values do not, as he had hoped, sit comfortably together, and his marriage is not the bed of roses he had envisaged as a young lover. ‘If you’re a whole person, you can be free anywhere,’ says Rhoda. ‘But we aren’t whole , you and I,’ he replies. The truth is that for all her disadvantages as a woman, Rhoda, unshackled by property and business, has a chance of freedom that he has not. Will she prove brave enough to seize it?

Delia, the youngest, having always accepted that she was the outsider in the family, favoured neither by her father, like Rhoda, nor by her mother, like Maurice, is not bound by the same tethers. Even as a child, when her older siblings longed for the holidays, she had thrilled to the excitement of school; as a young woman, she looks to the future, finding little difficulty in putting failure and disappointment behind her. Aware that she is not the prime recipient of her mother’s love (a commodity in very short supply), she makes no effort to secure her approval, and, as a consequence, meets her on equal terms. Having made the break long ago, the old home represents for her neither a refuge nor a prison. She does all she can to help her sister get free of Natalie’s clutches. Delia might have been impatient, Rhoda resentful, but, different as they are, the two have a warm relationship. Rhoda appreciates her younger sister’s life-enhancing qualities. Delia sympathises with Rhoda’s predicament.

More perceptive, and more objective, than either her sister or Maurice, she also sees in her mother, what the others are blind to, that ‘If she’d ever been taught to use her brains for herself, instead of depending on other people, she’d have been a very capable woman.’ The New House raises a number of questions about the position of women in nineteen-thirties Britain, a time when few upper-middle class girls needed to work, but not all were rich enough to enjoy much of a life until and unless they married. Rhoda rightly fears becoming like her mother’s spinster sister Ellen, selfless, kind and unregarded, and too poor and too old for any new venture.

Ellen, like Rhoda, has loved and lost in her youth, but she is capable, like her younger niece, of putting past sorrows behind her and seeing that the new house, which might turn out to be Rhoda’s prison, could be a haven for her: ‘If she could really be living in a house again, able to make a cake or do some flowers for the table, or look through the linen and see what needed mending.’ ‘Practised in resignation’, Ellen is a survivor. So too is the much younger Ivy, maid of all works to the Powells, and the first to settle in the new house, cheerfully making order, of a sort, in the confusion of kitchen utensils and china. She had, as Rhoda grasps, ‘been making herself at home in other people’s houses since she was fourteen. She had the experience and temperament of a soldier of fortune.’

Ivy will be the only servant. The new house boasts no green baize door. A new social order is dawning. The old house, already reduced to a staff of two, will be pulled down. As Delia observes, ‘there was a removal going on all over England that was turning out that cupboard [the cupboard into which families like hers had pushed away out of sight all the social mess that they did not want to confront], and a good job too, even if it spoilt the tidy room.’ Homes will be built for families struggling in cramped slums. There will be better jobs for women, and for some the freedom to live and love more like men, like Delia’s boss, Doctor Nella Dunn, who ‘pursued free love conscientiously, making new contacts like a good, but rather tired commercial traveller.’

The New House is a novel about a change, written, like many Persephone novels, at a time when undreamt of change was just below the horizon. It is almost impossible to close it without saying to oneself, ‘if they only knew …’