Germany, Spring 1921 – five children, conceived on the same summer night, are born, within days of each other, at the same hospital. Manja opens on 25th May 1920. The war is over. The future appears as bright as the sparkling lights advertising cafés and bars. The humiliation of the Treaty of Versailles signed the previous year can be forgotten; if the foundation of the Nazi party is a blot on the political horizon, it is a very small one; the man who will shortly become its leader is still a relative unknown. The novel ends in 1933. The children are twelve years old. Adolf Hitler is Chancellor of Germany.

Writing at the start of her English exile in the 1930s (Manja was published in Holland, in German, in 1938, and in English the following year), Anna Gmeyner, Austrian-Jewish by birth, was well acquainted with the political and economic situation in Germany, the social turmoil, the inexorable rise of Nazism. She had observed ever-growing anti-semitism as first hand. The word ‘liquidieren’ was already being used in connection with the Jews, ‘liquidieren’, to brand, or punish severely. Even when she left Germany in 1933, the word had not yet taken on the full force of ‘to liquidate’. Gmeyner set her novel in turbulent times, suspecting, but not knowing the depths to which the turbulence would descend. Her contemporary reader would have known as we do that the optimism of the opening page would be fleeting, that no good fairies attended the births of even the most fortunate of the children. They didn’t know and Gmeyner herself didn’t know what awaited them, their families, Germany and the whole of Europe. The horror was beyond all imagination. No need to apologise for the ‘spoiler’: we read Manja now, knowing that beyond the final chapter what awaits the children who remain are the War, and the Holocaust.

We may know more about the bigger historical picture than Anna Gmeyner could have known, but what she gives us in Manja is a moving, vividly detailed and utterly absorbing view of the lives of five very disparate families, lives which intersect, unpredictably but convincingly, observed not continuously but at significant intervals, at a time of profound uncertainty, of triumph for some and tragedy for others.

At the centre of the novel is the eponymous Manja, the only girl of the five children, loved, revered, protected in their different ways by the four boys, Heini, Franz, Harry and Karl (as in Marx). The children are eight when they meet– a shared lodging house for two, parental business link and shared school for the others – and pledge to meet regularly at their riverside wall: ‘till we’re big’, swears Manja.

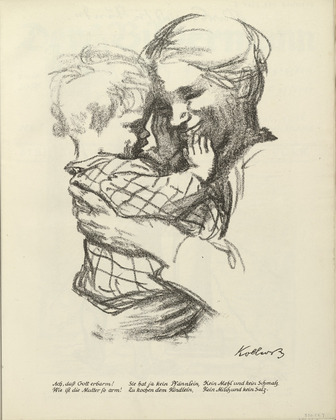

But their paths have already crossed: Heini’s father, Ernst Heidemann, a doctor, has saved the lives of both Manja’s mother and Harry’s after childbirth; Harry’s father, Hartung, a half Jewish businessman, profiteer and philanthropist has endowed Heidemann’s hospital and paid for him to recuperate, together with his family, from a troubling war wound; Karl’s mother, Anna Müller, has put Manja to her full breast, when the little girl’s mother lay between life and death. Franz Meissner’s family, the only committed Nazis cross the others on their way down – his father is dismissed from Hartung’s business– and on their way up.

By 1933, when the novel ends, it is the Meissners and their like who have risen to the top; Hartung has fled Germany, the Communist Müllers are living in fear; Ernst and Hanna Heidemann, are struggling to keep their liberal principles alive; Manja’s Jewish mother, Lea, so bright and young, passionate and impulsive at Manja’s conception, is set on a downward spiral, helpless against crude and vicious racial attacks, and against her own flawed character. The five threads are deftly held together.

Before writing Manja, Anna Gmeyner had enjoyed some success as a playwright, librettist and a writer of film-scripts: she brings all of those skills to bear in the novel, using a tight focus and discrete scenes to carry the complex narrative. The opening chapters describe the conception of each child, from the happy pre-marital embrace, to a cold coupling and a marital rape. If the descriptions are, for their time, sexually graphic, they are also visually graphic. She is a master, mistress, of detail bringing characters and settings to life with stark realism. Hanna, waiting for her fiancé, Ernst, to return, desperately passes the time counting the repeat of the purple flowered wallpaper in her pension bedroom; Lea, embarrassed by her poverty, is careful not to hang her clothes over the screen in the hotel bedroom, because the straps of her petticoat are fastened with safety pins; Hartung approaches his wife in striped green pyjamas, reflected and distorted in the mirrors he has placed in the bedroom to ‘capture and multiply his wife’s beauty’; Anton Meissner whistles as he unlaces his shoes, looking at the thin little plait of his wife’s hair. Twelve years later when the Meissners have left their cramped little apartment and are enjoying the wealth that comes with their fierce adherence to the new political correctness, Frieda will raise her eyes from her plate over dinner, looking up ‘from the intertwining wreaths of little roses between puddles of gravy’, and see Anton with ‘strawberry jam clinging to the corners of his mouth and his moustache’. Jam and gravy, the crude symbols of new money, new status.

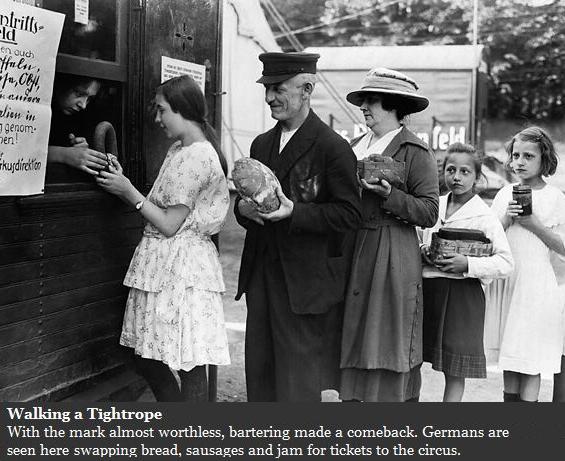

It was not Gmeyner’s intention to provide a social history of what we think of as the ‘inter-war years’, but the details of everyday life at different social echelons (themselves in a constant process of fluctuation), tell a stark story. During the worst years of the Depression, Frieda Meissner’s head had ached from trying to tally the household accounts, ‘There were no pfennigs now, no marks either, not even in hundreds or thousands. One spent billions and was still poor…’ The daily reality of soaring inflation left Frieda, struggling to make ends meet, to keep her family fed. She looks for someone to blame: across the courtyard, where there is sun enough for flowers, she finds her scapegoats – a prosperous Jewish councillor, with a maid, a wife with plucked eyebrows, jazz (negroid music) on the gramophone – ‘Jewish scum, taking baths in champagne.’ Meanwhile, to her embarrassment, she cannot pay Anna Müller for doing her laundry. Anna who is compelled to take in washing because in the prevailing political climate her Communist husband can no longer find work: ‘Reds’ are also being targeted, but Anna is resourceful, and kind and brave, like her son Karl.

In the background the ring of boots on cobbles can be heard, young men in brown shirts are marching; before long Germans will be greeting each other in a new way, ‘Heil Hitler’.

The five children are growing up, becoming aware of the complex tensions within their families and beyond: Karl’s sister is in love with a Brownshirt, his father is in hiding; Franz’s father is seducing the maids, even the Heidemanns’ solid, loving marriage shows signs of strain. Harry’s mother is mad, his blind but kindly Jewish grandfather is an embarrassment, his father’s business practices are under scrutiny; Manja’s mother is neglecting the children, and making a living in the only way she is able; Franz can meet Harry only in secret. Manja must sit on the ‘Jewish bench’ at school. Good teachers are losing their positions, good doctors are leaving the hospital, good lawyers are fearful for their jobs. Bad people are beyond the law, untouchable.

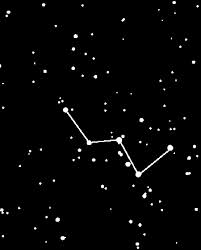

Manja had likened the children to the five stars of Cassiopeia. A year later, Franz, torn, more than the others, between his friends and his family, reflects that his new Hitler Youth comrades would describe the little group as ‘the sons of a racketeer and ungodly Liberal, a dirty little Polish Jew and his Red school friend’. But their loyalty one to another is unfailing, the wall, ‘a reef against which the flood of events impotently dashed itself’; better not to look forward when one comes to the end of this remarkably rich novel, but hold faith with Anna Gmeyner, wishing that it might remain so.