Someone at a Distance is quite different from William and Mariana, which involve young, central characters and have plots which follow their development as individuals. Someone at a Distance is a novel about family life, about a small world that is torn apart by the arrival of an outsider.

The scenario – a middle-aged married couple with children, an attractive, younger woman comes along and the husband has an affair – is relatively simple (Dorothy Whipple herself described it as ‘a fairly ordinary tale about the destruction of a happy marriage’). But the way the scenario plays itself out is gripping. Like the opening scenes in a horror film, the early chapters of the book give a glimpse of a dark figure lurking on the sidelines while the main characters remain blissfully unaware of the danger. The book captures the changing psychological states of the characters and the flux of raw, underlying emotions, beneath some of the most simple, everyday scenes.

Louise, with her ‘clear-cut, almost exquisite finish’ could almost be Madame Bovary re-incarnated (and indeed her identification with Emma Bovary is made explicit when she reads to Mrs North from that novel). Like Emma Bovary, she is driven by the need to find a way out of the ‘excruciating boredom’ of provincial life. She does not set out to pursue Avery from the outset, she adapts to the situation as she goes along. On her second stay at the Cedars, there is the first indication of an attraction between her and Avery. But she nevertheless returns home and announces to her parents that she will marry the ‘horribly provincial’ Charles Bovary-esque Pharmacien, Andre Petit. Then chance cuts in: she changes tack when, the very next day, a letter arrives from Avery announcing Mrs North’s death and the legacy of £1,000. So she returns and installs herself at Netherfold where ‘gradually, the French scent stole under her door faintly permeating the atmosphere changing it, establishing her presence’.

It is a series of small things that lead events to take the course that they do. As the author notes, ‘there are times in our lives when the slightest move is dangerous’. Avery brings home a box of marron glacés for Louise. The gift becomes a secret between them because Ellen is, by chance, out, and when she arrives back, Louise takes the gift to her room. It is clear that Avery doesn’t realise quite what he is doing, but at this point, he becomes somehow committed.

Louise has ‘no particular design’. She is attracted to Avery and, as an attractive woman, feels entitled to his attentions. She is ‘ready to follow any advantage that was offered’, she is ‘casting about’. Once she has Avery’s attentions, she has control and is ‘in her element’ as the situation unfolds. She has honed her skills of deception in her earlier relationship with Paul and now she is excited to be ‘back in the game’: it is what makes her feel ‘truly alive’. And she relishes this situation even more than her previous relationship with Paul because this time, ‘the power was all herself’. Her motivations for ‘the annexation’ of Avery are about avenging herself on Paul and restoring her confidence in herself. As when she successfully concealed her relationship with Paul from the people of Avigny, she despises those that she can easily fool. Ellen ‘didn’t deserve what she had if she couldn’t keep it.’ Her envy of what others have is part of it: envy of Paul and Germaine, of Avery and Ellen, of wealth, of their ‘mediocre happiness’. When Avery and Ellen go to visit Anne at school, Louise goes through their things. She enters their sunlit room where ‘all was serene, charming’ and is gripped by ‘a sudden violent wish to upset it all.’ ‘Why must she always be the one on the outside?’ she asks herself. She is at a distance, from other people, from the world she looks into.

Louise is also driven by a bitterness about men and the fact that a woman like her must rely on them to get on in the world. During her time at Netherfold, she briefly seeks to build a ‘feminine partnership’ with Ellen in order to isolate Avery and tries ‘to strengthen Ellen’s hand by putting into it some of the cards she herself considered essential to the feminine game’. Her bitterness about the power of men is deep-seated. When Avery tells her to go home, she is infuriated because he is handsome, and is in a position of strength because of his wealth and his ‘maleness’. When she hears that Paul’s wife, Germaine, is expecting a child, her reaction is equally strong: ‘men had everything – she hated men, but unfortunately it was through them that women had to get what they wanted, at any rate, women like herself.’

Avery is good-looking and likeable with an air of indolent well-being. He gives way to his attraction to Louise ‘in a lazy amused way’, assuming that he has control over the situation. But it becomes all too apparent that he doesn’t know his own nature. He has an obsessive streak which surfaced in his pursuit of Ellen before they married and which resurfaces again in his relationship with Louise and when he leaves Ellen. There is ‘excess’ in his nature and it is an ‘excessive pride’ that prevents him from returning. There are rare moments when a softer side of him is apparent: Ellen describes a moment by her bedside after the birth of their first child when he was ‘so absolutely himself, so much hers… shorn of minor vanities and petulances’. She also is touched by his devotion to Anne. When they visit Anne at school, she ‘feels an intensification of her constant everyday love for Avery’ because he ‘gave himself entirely to being Anne’s father and ‘he was happy in a deep humble way’. This ‘knitted them together, indissolubly, or so it seemed’. Indeed, their unity as a couple seems to derive largely from their children, particularly Anne: ‘Anne’s name had only to come up for them to chime together like a pair of perfectly synchronised clocks’.

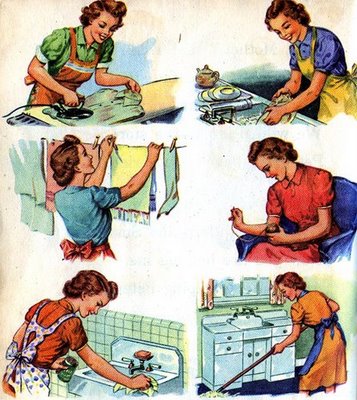

Ellen, on Louise’s analysis, is too good to be true, too trusting, too happy. She is Louise’s opposite: slight, fair, with no idea at all of trying to make an impression, and is perfectly content ‘looking after things’. Surprisingly, Louise quite likes her but her main criticism of her is that ‘she managed her husband badly – she was unselfish therefore he was not. He took her for granted. She was altogether too open and simple. A woman needed art and subtlety, Ellen had neither.’ Earlier on, another outsider, John Bennett, has observed Ellen’s selfless running around after her family, and Avery’s indolence, and questioned whether Avery really appreciates her. As the distance grows between her and Avery, Ellen becomes acutely aware of the ‘mutual and unique confidence’ that had previously existed between them and realises that she had never acted without him. When she confronts Louise without discussing it with Avery, she feels as if she is ‘breaking one of the countless Lilliputian bonds that bound her’ to him. When Avery leaves, though she finds a way of coping, it is clear that its not easy for a woman in her position suddenly to have to fend for herself. As Mrs Beard says to her: ‘”you know how hard money is to come by for women like us? We’re not the new sort of women, with University degrees in Economics, like those women who speak on the radio nowadays, girls who can do anything. We’re ordinary women, who married too young to get a training, and we’ve spent the best part of our lives keeping house for our husbands. Not that we didn’t enjoy it, but now you’re out on your ear like me at over forty.’

There are a number of robust subsidiary characters in the novel, many of whom, in contrast to Louise, embody a sort of basic human decency: old Mrs North’s housekeeper, Miss Daley; Miss Beldon, Anne’s headmistress; Miss Beasley (who reveals that she also has a husband who left her); Louise’s ‘large, baggy’ parents; Mrs Brockington and even the rough-speaking Mrs Beard at Somerton. Most of the characters live within small communities: the village where Ellen and Avery live and Louise’s provincial home-town in France.

In Amigny, Monsieur Lanier opens the shutters each morning and greets fellow shopkeepers. Customers come and go in the shop and bring new gossip with them. Within this community, social position matters a great deal: it is why Louise cannot marry Paul, why Madame Lanier is so pleased when Germaine, Paul’s wife, invites Louise to host a stall at the town’s charity fete and why Louise’s inheritance is so gratifying to her parents – it gives her credit in the eyes of their fellow townsfolk. The descriptions of the Lanier’s routines and mannerisms make them very alive and sympathetic as characters: they tear up bread and throw it into their morning coffee where it bobs ‘like ducks on a pond’ and eat with great appetite wielding their ‘large leaden spoons’. Both parents defer to and even fear Louise, with her air of worldly sophistication. There is considerable poignancy in many of the scenes where the Laniers are altogether, particularly the scene where Louise’s parents anxiously await her arrival from Paris, standing on a dark, windswept station platform. Both parents are anxious to satisfy their daughter and are very conscious of how unsatisfactory they are in her eyes.

Ellen engages very little with the community in which she lives, because ‘her family was enough for her’. Nevertheless, there are descriptions of incidental characters here and there which give a flavour of village life: the cheerful ticket collector at the station, the one that Ellen and Anne both like; Ted Banks, the postman, with whom Ellen compares gardening notes. Their world is small and serene and cherished all the more by Ellen because of the dislocation war brought to their lives in the recent past. After Avery’s departure, Ellen finds refuge in another small community, at Somerton, which is also the place that she and her children found refuge during the war.

There is a sense in which Ellen loses and then regains her serene world as the novel progresses and, indeed, despite the emotional tension throughout the novel, all three of the central characters are happier when it comes to an end: Avery because he knows that Ellen, ‘the harmony of his life’, has forgiven him; Louise because she is calculating how she will manoeuvre herself out of her marriage to Avery with the maximum possible advantage to herself; and Ellen because she has learned to accept what life brings and because she knows that Avery is ‘restored’ to her.

22 replies on “Persephone Book No.3: Someone at a Distance by Dorothy Whipple”

A thoughtful evaluation of a wonderful novel –though I preferred

The Priory.

Gosh, I hope no one who HASN’T read Someone at a Distance doesn’t read it…..

Anyway, I was amused at your second question. Rather a wonderfully English one! How much more of a femme fatale Louise is. French, France, Paris. So seductive, so obsessed with clothes. In some ways the two main women are stereotypes of what one imagines and English woman/Frenchwoman to be.

Louise is such a mega-bitch. So cruel to her parents.

(Shakespeare, of course, set lots of things in Italy, where people are thought to be far more passionate. Hm…)

As regards France. The recent movie, An Education, played with this idea too.

So much more to write about. No time. However, a terrific book.

I cannot think why I had never heard of Dorothy Whipple until last year.

I just finished this wonderful book – my favourite Dorothy Whipple. I was distressed and anxious throughout, which I expect,was the exact emotion DW was looking for.

How stupid of Avery to fall for Louise’s ploys (how typically male…). Even worse, not to do anything to get himself out of the situation because of his pride. How dare he ‘do the right thing” by marrying Louise even knowing, by then, that he didn’t even like her. If he didn’t do the right thing for his family, why feel such an obligation to Louise? Bad enough to have had the affair, but then to go on with it and shatter everything just because he was too wimpy to stand up to Louise.

I didn’t love the ending. I was so irritated by Avery’s actions that by the end that I was hoping Ellen would tell him she no longer cared then he turned up. Sadly it was clear she was going to wait eternally for this wimp, who frankly deserved to be miserable.

English vs french? I think it made a big difference to the book that Louise was not English. The playing field would have been too even. Also Louise was masterful at using her ‘foreign-ness” as a play in seduction.

By the way, can anyone fathom what they didn’t kick her out of the house when she was waiting for the legacy? It was obvious they were annoyed she was staying, an also obvious she was basically moving in for the long haul. Why didn’t Avery (pre-affair) and/or Ellen insist she leave?

What an excellent essay on this wonderful novel! I have read all of DW apart from High Wages – I am ‘saving’ it – and though Someone at a Distance isn’t my favourite – Greenbanks would have to take that crown – I still think it’s a superbly crafted and characterised novel that knocks the socks off most modern offerings in Waterstone’s.

As for your questions –

1. My memories of this book are hazy at best but I do remember thinking that I didn’t think it was anybody’s ‘fault’ in particular – DW is very good at not passing explicit blame on Louise, because that would be too simplistic. Louise does purposely set about destroying Avery and Ellen’s tranquil marriage, but Avery allows her to, and Ellen doesn’t really put up a fight – it reminded me very much of Elizabeth Jenkins’ The Tortoise and the Hare in that respect.

2. Yes I think Louise’s Gallic charms are integral to her character – she has come from a different country, with different customs – she is the foreign ‘other’, and as such she is perfectly placed to upset the balance of the quiet provincial English life Ellen and Avery lead. Plus there is the connotation of the ‘femme fatale’ – French women have always been viewed as more sexy and predatory than English women, haven’t they?!

3. I always thought that the title meant that Louise had come from afar with latent menace to destroy the life Ellen had built. She was an outsider – ‘distanced’ – from the life she wanted to intrude. There is also the possibility of the title referring to how easily things on the periphery of our lives that we don’t deem to be important can overwhelm and destroy us quite unexpectedly.

4. I’m not sure what possessed Carmen Callil to dismiss DW in such vitriolic terms – her writing is far superior to many female novelists published by Virago! I find DW’s novels to be rich, emotionally engaging and beautiful written tapestries of ordinary life, and as such, I consider them true classics. I have read all bar one of her novels and each of them has delighted me in their own way, much like Austen’s novels. I wouldn’t be without Dorothy Whipple’s books for the world, and I think every woman (and man!) should read them. Greenbanks especially is a hauntingly elegiac book about love and aging and family and regrets that I would consider one of my favourite books of all time.

Someone at a Distance is one of my favourite Persephone books. Although the writing style is quite ordinary in many respects, the way Dorothy Whipple portrays the destruction of a happy marriage is so perceptive that it’s almost painful to read. I was so furious with Avery! I felt like shaking him to try to make him see sense.

I loved reading your essay about the story. It captures the essence of the novel and of the varied cast of characters. So far as your questions are concerned, here goes:

1. While I was reading the book I blamed Louise entirely. I know she didn’t set out to destroy Avery and Ellen’s marriage, but she did so with abandon, thinking only of her own selfish ends without any consideration for the feelings of others. It was obvious early in the story from the way she treated her parents and was prepared to deceive the inhabitants of Amigny that she was not a likeable person and not one to be trusted.

I didn’t at first blame Avery, dismissing him as the stereotypical male flattered by the attentions of a glamorous younger woman, unable to resist temptation and too weak to try to. But as the story progressed I became more and more angry with him for allowing pride to ruin everything he had held precious, including the feelings and confidence of the daughter who so adored him.

2. Louise could just as well have been English, but she wouldn’t have seemed so alluringly different. By comparison with the people Avery was used to meeting, a young Frenchwoman would seem far more exotic and alluring.

3. I took the title literally – Louise was French and therefore ‘at a distance’.

4. Dorothy Whipple’s writing style might not be the most sophisticated or poetic, but it’s fluent, easy to read, and grammatical, which is more than can be said of some modern writing! I think Virago’s founder is being rather stuffy in drawing a ‘Whipple line’. I haven’t read any of her other novels yet, but this one’s a gem.

Could write reams more on all of the above but no more time!

Meant to add to my answer to question3 above but was interrupted and fogot to go back to it.

I also thought that the title hinted at the distance between Louise and Ellen in terms of their respective moral standards and values, and between Louise and her parents’ aspirations for her.

Great post on the book! This was my first Persephone book, but I’ve already ordered Fidelity to follow up.

To answer the questions:

1. I put Avery at fault as I read. My reasoning is that although Louise is definitely NOT a nice person, she’s not the person who made a vow to Ellen. Avery made the commitment and so gets the larger portion of the blame.

2. I think Louise being French probably made a difference, particularly to Avery. Aren’t French women notoriously sexy?

3. I love the comparison of the title to quantuum entanglements, and only wish that I had thought of it (or had even heard of quantuum entanglements). I interpretted the title to signify how distant all the adults were – Avery from both wife and mother, Ellen from neighbors, Louise from social norms and mores.

4. I think Whipple compares favorably to contemporary popular female novelists (Jodi Piccoult, Anna Quindlan, Sue Miller come to mind). I wouldn’t put her up against authors like Margaret Atwood or Joan Diddion. I guess I would agree with the assessment that she’s on “the lower end of quality writing,” but she’s definitely in the ballpark.

Am very new at the forum stuff so please,feel free to correct me when I go worng!I began reading Dorothy Whipple when I found her on the reading list here and decided to use this period of women’s writing for my disertation for my Masters degree. She has been a joy to discover but my favourite is ‘They Were Sisters’. ‘The Priory’ is also a very well observed novel on the relationships between women in a family and,indeed ‘Someone From a Distance’ does the same thing.I think this is her strength, the way we relate to each other as women and how we judge each other and above all how we implode within our relationships as women. Don’t know how many of you out there have read the short story collections Persephone have published from the same period but they are excellent and worth a read to give a snap-shot of the time.

I have always loved Someone at a Distance, for me it is a perfect summer reading book because, like all Whipples, it’s complex enough to interest, but so beautifully written that it’s very easy to read.

I’m not sure that I think that any one person is to blame, because for me the way the characters are drawn means that they would almost inevitably have acted in this way. Avery is quite a self-obsessed person with a good opinion of himself that many share, but quite weak with it, so the flattery of a younger, attractive exotic French woman would have completely gone to his head, and because he does not seem to be overly bright, and also lives quite a lot in the moment he would not have necessarily realised what he was getting into.

Ellen, being very sheltered and in many respects naive, would not have realised either, and the fact that she defers in msot respects to this rather weak, vainglorious and non-too-bright husband means that she doesn’t have the strength or self-knowledge (which only comes much later) to see what is happening. For me, Ellen has also always appeared the tiniest bit smug in her nice, middle class home with her lovely family, so I can see why she jars on Louise.

Louise, possibly somewhat more than the others, but then, she has been indulged, but misunderstood, by her parents her whole life, and firmly believes that she is made for better things than a provincial shop because she is good looking and smart in a cunning sort of way (Slightly OT, but similar to Janey in Louise Levene’s A vision of Loveliness). Because of this I think she will tend to think of herself first to the exclusion of anyone else, and other people’s thoughts, emotions, beliefs simply do not matter in her scheme of things. Rather people’s standing, possiessions and appearance are the crucial issues for Louise.

Paul, I think is a catalyst, but no more.

I think the fact that Louise is French is quite important. Had she been English, she would have been easily pigeonholed into a class stratum, be it middle or working or some other permeatation of this. I do not think she would have been able to insinuate herself into the family in the way she did due to the rigidity of the English class system. Old Mrs North, for example would not have wanted a working or lower middle class English girl with the wrong sort of accent reading to her or looking after her. The fact that Louise is French means that she is outside the class system, and thus has freedom to be who she wants to be. Being French as well implies a certain shorthand – elegant sophisticated, beautifully groomed and dressed, exotic, but not too exotic. Although there are obviously women from other European countries who fit this description, the convetional stereotype is that of a Frenchwoman, so it would have been harder for the novel to flow, I think, had it been a German or Belgian or Spanish woman.

I interpreted the title of the novel as being that they are all “someone at a distance” to other characters in the novel. Louise and Ellen obviously have no idea what makes the other tick, Ellen and Avery have little idea of each other as a person, as opposed to the facade of wife/husband, neither Avery or Paul see past Louise’s beautiful exterior. Possibly Anne and her horse are the characters with the strongest awareness of each other!

I think Carmen Callil is completely wrong, but I understand the context in which the comment was made. When Virago started in 1973, it was at the time when the concept of women’s liberation was making major impacts on society. Dorothy Whipple does not belong in this context. Beautifully written though all her novels are, she writes, much like Austen, about comfortable middle class families and their issues. In Whipple’s books, people have enough to eat and good homes, even if they are decaying somewhat, like the house in The Priory. They have servants. There is a class system that is rigid and unyielding. They were emphatically books about another time, about a world that people in the 60s and 70s were trying to smash and I think Callil mistakes the unfashionable content for the way it is written.

Gina, you have the right idea about the title in that the characters think they know each other but actually have very little idea of what makes them tick. I think this how we are in real life and it takes major crises to show that to us. Anyone who has every been through the seismic shift of a broken marriage will know Ellen’s alienation from all she holds dear. The author tells us, though Louise, that ‘we’re all careless’ and Ellen and her family, in the golden glow of their daily life, could be considered careless to the point of complacency before the event which shatters it and them. But how should they have been otherwise? How could they have been saved? They couldn’t. Human beings are weak, things happen, blame isn’t relevant.

Also, like most women, Ellen has unwittingly made herself subservient to every member of her family, including her mother-in-law. They all manipulate her. As usual, it takes the friendship of strong women, like Miss Daley and the owner of the gentlewomen’s residential home, to see Ellen through. Does it sound like I know of what I speak?

I don’t mean to imply in any way that Dorothy Whipple is derivative or imitative, but she does stand in good company. Her expression of the way in which life goes on in tiny little ways while Ellen is fighting for her life – in her description of a petal falling from a rose in a vase on the sideboard – is an echo of Virigina Woolf in ‘The Waves’. Her depiction of Ellen’s stillness as she copes with the immensity of Avery’s betrayal reminded me of Isobel Archer spending the night without moving from her chair as she contemplates the revelation made by the look which has passed between her husband and Madame Merle in Henry James’s ‘The Portrait of a Lady’. I’ve been there. I know it. And if you haven’t, all three of these writers can tell you exactly what it’s like.

I must add that, now I’ve read it, I think the cover of the Classic version of the book is perfect. That lovely, mature face, distanced from everything, turning it all over in her head, trying to find a way to survive.

Am now reading ‘Because of the Lockwoods’ a title which sounded to me a bit childish and ‘School Friend’-ish. I was wrong to dismiss it as it is relevant, though not enigmatic like ‘Someone at a Distance’.

Majorie, I have also just read Because of the Lockwoods and it’s excellent – you’re in for a real treat. Definitely not as simplistic as it first appears.

Gina, I love your point about Carmen Calill – I hadn’t considered her comments from within the context of the 70’s when Virago was formed. Dorothy Whipple clearly wasn’t enough of a revolutionary or feminist to be considered relevant to the Virago list, though I would happily contest this. However I don’t see how the likes of Molly Keane and E M Delafield were considered any more ‘relevant’ to the modern woman – perhaps their use of witty irony won them extra brownie points!

A week of rain during my Cornish holiday has given me plenty of time to read this one! As I read, the phrase “cutting of his nose to spite his face†kept coming to me. Avery must have passed that gene on to his children too as they both pulled the shutters down and cut ties just as quickly and unbendingly.

As to who is to blame, I’d say cunning Louise and proud Avery but also stubborn Anne and weak Ellen. I was amazed at how much influence Anne had. Ellen bows to Anne completely to maintain their equilibrium. Surely even back then a parent would attempt to have a rational conversation with their child? It’s not as if Ellen was in an hysterical, self-obsessed state herself. She seems stoic. Anne is even allowed to dictate to her mother that her school is not to be informed yet I would say it is Ellen’s duty to do so, especially as she is a boarder and the school is under an obligation to act as guardian. Anne is the reason that Avery feels shame and that Ellen will not push for reconciliation. Hugh too has the power to influence his father’s career. Both children, who don’t even live at home, by their actions, dictate Ellen’s future. I find it hard to see how a family that is so cloyingly, politely jolly together, that seems so bonded, can be broken up so thoroughly, so comprehensively, within the space of time it takes Avery and Louise to drive away from Netherfold! Was the marriage just a flimsy façade after all?

As Louise has to be French for the plot, so the Norths have to be British. Louise being French (although Louise doesn’t sound like a French name to me) is perfect for the plot. It means she is an unknown quantity which the family can’t quite handle. The language difficulties and behaviour differences allow her to say things which take you aback with their bluntness, they are so un-English. I wanted the Norths to stop being polite to that cow, stop being so British and just chuck her out! She showed that she was cunning and willing to take whatever she could, whether it be Ellen’s corner of the sofa, the contents of old Mrs North’s home or Avery. She took complete advantage of them by living rent free and idly while obviously just waiting for her inheritance. Why weren’t the Norths more offended by this, more quickly, especially when the money she was waiting for would have been theirs?! I was so relieved when at last her parents stood up to her.

I’ve now read three Dorothy Whipple books, with High Wages as my favourite, and look forward to reading more. I do enjoy contributing to this forum too as it is a treat to write down my thoughts on what I’ve read. I am sure my Eng Lit teacher would have returned my work with a low mark with a note to say more quotes required as evidence!

Gina has said just about everything I would say about this novel.

I would just add that when I read of Carmen Callil’s comments some time ago now I thought thank goodness for Persephone! I adore Dorothy Whipple – beautiful, subtle, understated and with an intense grasp of human psychology and of the tiny details that go to make up a real picture of every day life. Maybe she does not stand with Margaret Atwood but then I can’t stand her books (and I have tried to read them!) so clearly they are on different parts of the spectrum.

It’s also worth noting how well DW’s books stand the test of time – perhaps because of the way she focuses on human foibles which are timeless. Even in our liberated 21st century modern world we all relate to the basic situation in the novel.

Who is to blame? The dastardly Louise, the weak willed Avery, the blissfully happy Ellen? In this confluence of life lines, it would be hard to pin blame on just one character but I’d place my bets on Avery. Although Whipple gave us a few hints of his streak of impulsiveness, the way he pursued the young Ellen until she succumbed to his entreaty to wed, I still hold him largely responsible for the breakup of the happy home we were privileged to glimpse at Netherfold.

It is Avery who saw the flirtation coming and did not head it off. It was Avery who felt he had to buy Louise her very own box of glaceed marron and then did not set the record straight when she hid them. It was Avery who did not boot Louise out on her ear when she made a pass at his son. And it was Avery who ultimately allowed himself to be seduced under his own roof. Furthermore, It was Avery whose huge pride would not allow him to cool his heels and make an attempt at reconciliation because he “wasn’t going to eat humble pie for the rest of his life”.

And yet, I pity him as he crumbles under the weight of what he has done. Sitting in the cathedral in Amigny, he allows himself thoughts of Ellen. “He thought almost all the time of her. She was the only one who could have understood what he felt and suffered: and he was cut off from her…”

Of course, if Avery had had the moral turpitude to resist Louise, we would not have had a story and so I must accept his weakness. I must accept the supreme selfishness of Louise who cares for no one but herself just as freely as I accept Ellen’s loving, housewifely way of making a life for the family she loves. And so I do. And with thanks to Dorothy Whipple for presenting me with a great story, rousing my emotions as she carefully builds the characters and their little quirks that all meld together in the end into a fine novel about the nature of love and pride. Are they mutually exclusive, the pride and the love? In the end we see a balance beginning to come into focus for Ellen and Avery. I think there’s little hope for Louise.

This is a book I’m having trouble “getting into.” Having written that, it seems Miss Louise has been a handful since birth. Clearly her parents hadn’t a clue how to raise her, and her intense self-absorption might have overthrown any effort on their part.

It rather reminds me of a 1950ish movie, and if I can ever remember the name, I’ll add another post. The dark heroine commits suicide just to keep two people from finding happiness.

Louise is such a character, and experience provides too many of these for me to enjoy reading about another just now. I wonder if Ms. Whipple knew a few, too.

My large, old library doesn’t have *any* Whipple listed. So I shall hunt bookstores to see if I can locate another of her books.

Meanwhile, I shall continue slowly making my through this volume, with frequent sojourns to other authors for balance. (Already have the library’s copy for next month.)

Everyone’s comments here are much appreciated.

Thank you!

D. Ellis

Have just listened again to the tapes I made of ‘Someone at a Distance’ being read as book at bedtime on Radio 4 a while back by Emma Fielding (I think) – marvellously brittle voicing for Louise . . . .

I’ve completed this book, and really am a little astonished at how vividly I’ve thought about the characters.

1. Who is to blame? All seem to have shared in this, but I feel Louise and Avery would be head of my list, with Louise at the top.

2. It seems to be very significant; however, I’m not British, so take with a grain of salt!

3. I’m not any good at interpreting what titles mean, so can’t hazard a guess at this one.

4. Hm. To have been so engrossed in a novel, given the subject was personally unpleasant, is unusual. Having read only this Whipple book, I can’t say; but I am trying to locate other things she’s written. She does impress me as a writer.

I’m so enjoying these books, and have told many people about this Forum, too.

D. Ellis

I wish I had a Persephone for every time I’ve read of an author being likened to ‘a modern Jane Austen’ – or similar! Usually inappropriately. Barbara Pym probably comes the closest. I’ve enjoyed 3 Whipples so far, and I don’t think the writing compares to the subtlety and wit of ‘the divine Jane’ – but DW has her own style and creates her own, mainly credible, characters. I must confess I’d never come across Dorothy Whipple before I became a Persephone reader, despite starting my career as a librarian working in public libraries.

Was Carmen Callil being intellectually snobbish when she made those remarks, or maybe provocative? The publishing scene was very different when Virago started up, now that there is more competition to publish women writers I’ve noticed their selectivity has altered. (Dare I say standards lowered?) If Carmel Callil made the same declaration about Mills & Boon, or what we call ‘airport fiction’, I could understand it, but many people only read that kind of book – and at least they are reading books – which can’t be bad.

Comparing women writers is always subjective, and unfair – like apples and pears they’re different, they reflect their own times and values. Books to me are a little like food: sometimes I want more demanding, thought-provoking , educative reading; other times it’s good to fall back on something light and easily digestible – like pasta. Whipple is the pasta.

As to blame – firstly Avery, if he hadn’t been so weak and smug Louise wouldn’t have succeeded. But Louise cold-bloodedly engineered the marriage break-up so she is equally to blame. Even Ellen should have acted differently – but she did cope and gained the confidence to re-make her life. The fact that Louise was French made the story more credible, but such a self-centred woman might just as easily been British, albeit less exotic.

I loved this book! I thought it was such a sinister story and I could feel the suspense building slowly. I saw it in my mind as a 40’s black and white horror film, even though it was written in the 50’s. Horror, in that you could sense the catastrophe ahead but could do nothing about it. Actually, it reminded me a little of Rebecca – the film.

I couldn’t believe that the North’s would put up with a girl like this. Why didn’t they just demand she leave? I suppose they were too polite. I placed the blame with both Louise and Avery. I agree with another comment; the family seemed to dissolve so quickly that you wonder what they really had between them all originally. Why didn’t Ellen make more of an effort to be honest with Anne? I found her weakness and resignation really difficult to understand.

I couldn’t understand why Avery would go off with Louise after the scene in the living room. Why didn’t he at least try and make an effort to explain to Ellen what was happening and demand Louise leave? I know things were happening in the house between them for a while (was there a discreet hint of a bedroom scene one night or was that just my imagination?) but he obviously wasn’t in love with her so why leave? Just to satisfy his pride?

I took the title to mean Louise originally, as she came from a distance; France. But toward the end I thought perhaps it could mean Paul or really any faceless, unknown person. Somehow it was written towards the end of the book that people totally unconnected to you could impact on your life without you or them knowing it. Louise was thwarted by Paul so he was the catalyst for the catastrophe. Maybe?

I’m very keen to read more of Dorothy Whipple’s books and I must say I’m really enjoying this forum!

I have so enjoyed the above discussion about Someone

At a Distance, even though I havn’t read it. I am however currently reading The Priory… and found the Whipple discussion very relevent.

I have struggled with The Priory, my first Dorothy Whipple. The subject matter and era are completely up

my street but I have a big problem with the quality of writing. Just can’t stand the way Dorothy Whipple ‘tells’ rather than ‘shows’. I’m all for a good plot and a bit of narrator input, but there wasway too much telling in The Priory for me to consider it a great or well written book. There were moments of genius: penetrating insight into human emotion and good dialogue, but then came annoying big slabs of ‘telling’ what characters felt rather than getting under their skin and describing their feelings. Based on this novel I feel I understand the Carmen Cahlil comment and agree! I would not put Dorothy Whipple in the same category as EM Delafield, Bowen, Pym. Comparing her with a contemporary ‘domestic’ middle class author like Alexander McCall Smith, she also falls short in my eyes. Perhaps I should read another one? (I have an ancient copy of They Knew Mr Knight somewhere.)

I have only just discovered this discussion site and am throughly enjoying it. It is sometime since I read Someone at a Distance and my recollection is that after reading it I got very cross with Ellen and thought Avery a wimp. However, re Carmen Cahill, I used to work in a bookshop and remember Virago books starting up. Carmen Cahill has always had literary tastes but I think their list is fantastic. I have quite a collection and not one of them has been money wasted. The same goes for the Persephone list, but how can you compaire McCall Smith with any of the writers from either list? His books reveal him (rightly or wrongly) as the most patronising know-all of all time!

On the “someone at a distance” bit – they are all at a distance at many points and in a variety of ways. And the distance is from many things: one another, the marriage, and, at times, from themselves.

For a book in which the reader is caught up in what happens, takes sides, gets worried, and so forth, the protaganists are at the same time curiously detached from their actions and each other and yet (of course) involved & hurt. They are watching their actions as they carry them out. Other Whipple characters do this, too, but in this book all the adult characters seem to do so.

Callil’s comment highlights perhaps the fear in the world of “women’s” writing during the early feminist era, in that books like Whipple’s, dealing with the domestic and small-scale, cannot be held up as literature because they don’t deal with the larger scale or world issues that allegedly proper literature – usually but not always written by men at that point – does or did.

While obviously a comment on Whipple, it articulates a concern about what proper literature is seen to be, and how traditional women’s concerns were at that time seen as lesser or embarrassing. At a time when it was still being argued that women could write literature (& do many other things), for samples of women’s writing to be about wives being left or staying home & cooking was not deemed approriate. Like the renewed interest in cooking and craft, the development of what we are comfortable with as women’s writing has broadened as the acceptance of women as equals throughout society has become strong.

I think mainly Avery was too blame. As several have said- he was married and Lousie wasn’t. On the other hand she clearly worked hard at “entrapping” him and studied his weaknesses.

Re- not kicking her out. When I lived in London, there was one six month period that whenever I went out with a set of friends we were all comparing notes on how to get rid of unwanted houseguests. They came to stay for a week or so til they found a job and flat and were still there a few months later. Doing just enoughround the house that people felt guilty about trying to get rid of them. It can be hard when you’re polite and expect reasonableness….

Re virago- many of their books are unreadbale anyway.

I agree that Ellens children have too much sway (clearly bossy children are not a modern phenomena) alhough not tellin the headmistres makes for a good dramatic revelation with the newspaper