As the title suggests, The Children who Lived in a Barn, belongs to the ‘home alone’ genre of children’s fiction, in which, in order to survive, children are required to assume quasi-adult roles. The underlying premise is that for children to grow up they need to be freed from the shackles tying them to the nuclear family, a process, which in real life and ideally, is gradual. In fiction, and possibly in life, uncles and aunts, preferably great uncles, or great aunts, or an easy going grandmother, can all be relied on to allow more slack than parents, but with limited risk. The true test, through which the child reader can live out to the full her dreams of independence, comes when through some disaster (not too big) or emergency (relatively short-lived), playing mummies and daddies turns into the real thing, and the children turn out to be as good if not better at life than the grown-ups.

The children-abandoned theme is not confined to the junior shelves., think Lord of the Flies, or Ian McEwan’s The Cement Garden, among others, but when served up for adult readers the abandoned children are inclined to develop less appealing adult traits, savagery and murder, incest and cross-dressing rather than a latent talent for sailing, cooking, mending and chopping wood. Unlike Golding’s schooboys, or McEwan’s orphaned family, Eleanor Graham’s children do not turn feral, far from it – 11 year old Bob carries on wearing a tie, even at home, while Susan remembers to pack tablecloths when they move to the barn, and uses them.

Poor but ‘gentle’ (as in ‘gentleman’) is how the Dunnet children are viewed by the village. As a family, they had been considered stand-offish and eccentric outsiders. Daddy is a grumpy, reclusive writer, with ‘views’, who sends his children to the village school (Bob, naturally, will be going away to school later – where will the money come from?) but hates the ‘filthy little country buses’. Clearly brought up in the school of Commander Walker, whose famous telegram, BETTER DROWNED THAN DUFFERS IF NOT DUFFERS WON’T DROWN, opens the way to all the adventures in Swallows and Amazons, his comforting words to his wife as they leave the children are: ‘They can manage perfectly well by themselves, and it’s quite time they had a shot at it ….’.

As things turn out the children prove to be rather better at life than their parents, who, for the purposes of the plot, prove to be total duffers, missing their plane because ‘they had gone off to buy papers or get postcards or something’. Even Eleanor Graham herself doesn’t seem quite convinced: that ‘or something’ is a little vague. And when they finally return (sorry to give away the plot, but this was a Puffin book so it wouldn’t end badly) their explanation for their extended absence and failure to write is lame indeed: six months in a remote mountain hut, too far for them to walk to the nearest town (fortunately not too far for the old man who had rescued them: Sue and Bob would have managed), and loss of memory brought on by the plane crash. ‘“Funny”, murmured Sue’, when her mother laughingly says, ‘and we remembered that we had a large family waiting for us here in Wyden’. Funny indeed. And when Dad adds his own self-glorifying account of struggling back without passports or papers or money, one does wonder whether the Dunnet children weren’t better off without their hopeless parents.

The parents are somewhat unconvincing, shadowy characters, barely missed or mentioned by the children, but they are swiftly removed from the scene and the five young Dunnets are delightful, individualised and sufficiently well drawn to keep the reader, even the adult reader, rooting for them. Apart from Alice, who is only seven and in 2012 would barely be thought capable of washing up a cup, all the children have a thoroughly admirable work ethic, a sound moral sense and a real desire to contribute to the common good. We must, grudgingly, accept that they have been taught something in their short lives. Unusually for a middle class family of the period they have no staff, and Sue is well-used to helping around the house, and knows that clothes, and bodies, must be regularly washed, and food put on the table for her little family. Bob has a few skills, ‘carpentry and odd jobs, mending bells and putting a dab of paint on door or wainscot’ and some very clear ideas about role definition. He does not consider cleaning of any sort ‘as man’s work’ and is adamant that ‘men always carve’. Neither mending bells (presumably the kind used for summoning maids) nor carving will be much called for but his woodworking will prove invaluable, when it comes to making the famous hay-box.

Eleanor Graham captures the moments when, cruelly evicted from the family home by an unfeeling landlord, the children find the fun of playing house tempered by exhaustion. Sue ‘felt rather important and sometimes a little sorry for herself’; when the satisfaction of having got everyone through the day is perhaps not quite enough, leaving her, and Bob, ‘tired but fairly contented’. Only fairly contented. Sue is an extraordinarily engaging character,stoical and brave, holding fast to her (downtrodden?) mother’s dictum, ‘trudge another mile’, but not smug, recognising that ‘she herself had been far better tempered with Mother to rely on for things’. We share her delight at turning the barn into a tidy home with a jolly fire crackling in the stove, but we must also share her humiliation when the well-meaning but thick-skinned schoolteacher suggests that the other children spend their sewing lessons making clothes for the little Dunnets; and her anger with the District Visitor, who utterly fails to sympathise when the leaking barn roof ruins her efforts to keep things spic and span for the weekly inspection. Bob is all for complaining, and rightly so, but pragmatic Sue knows better: ‘Complain’, she said, ‘who to?’. At thirteen, she is uncomfortably aware of their position in the village. To the powerful trio of middle-class women, the doctor’s wife, the rector’s wife and the District Visitor, aptly named, Mrs Legge, Mrs Godly, and Miss Ruddle, they are not five (probably) bereaved children desperately in need of a home and some TLC, but rather a problem to be solved. They are trouble, the children of outsiders, ‘the sort of people’ who don’t have ‘aunties’, in Mrs Legge’s dismissive words, for whom a Home (capital H), Adoption or an Orphanage represent the obvious solution, and the most expeditious. These women, who surely see themselves as ‘do-gooders’, are of the sort whose interference falls well short of generosity or even simple kindness.

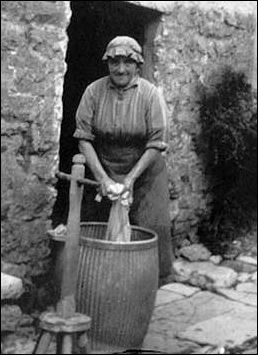

The cottage people, by contrast, cannot with their own limited resources, offer much, but they help where they can and they do not interfere. Eleanor Graham makes some interesting social observations. Men, on the whole, are kinder to the children than women. The baker repays Sue’s work on his books with stale bread, the grocer generously undercharges, the barber cuts Bob’s hair in exchange for floor sweeping, which isn’t a bad deal for the barber, and most importantly of all Farmer Pearl offers them the barn, and trusts them to put it to rights, while Mrs Pearl carps that she doesn’t want ‘a brood of children stroodling in and out of her kitchen with dirty feet all day long.’ Mrs P warms a little and later shows Sue how to cope with the family laundry, just as she had done herself as a girl. Poor women are kinder than middle-class women. They have known what it is to share the caring of the men-folk with their mothers from an early age. They respect and support the children’s efforts.

As adult readers we know that adults could and should have helped, but this is a novel for children, a novel in which children overcome adversity. Their economic needs are simple and the children can enjoy the satisfaction of meeting them. Sue worries about the immediate future, where she will find the money for new clothes, or a haircut for Bob (that dates the book almost as much as his tie), but on the whole challenges come one at a time and with a little ingenuity and courage they can be managed. Grown-ups may not help, but apart from one, they have no sinister intentions, they can be trusted not to harm; a visiting tramp is colourful and offers useful lessons in survival, an invitation into a stranger’s house is no more than that. It is a beguiling escapist read, a journey back to childhood reading and to a distant utopian rural England, where missing children late at night are a worry but not a reason to summon the police.

Escapist but in its way instructive. As a publisher Eleanor Graham was keen to promote non-fiction for children. Her vivid descriptions of the construction and use of the hay-box and of wash-day at the farm spring from the pen of an educator, as do the reams of proverbs spouted by Solomon, the tramp. She reminds us too that at thirteen Susan was only a year below the school-leaving age, only months away from starting ‘real’ work, in domestic service, while Bob, at twelve, might go to ‘industrial school’ to learn a trade. For children of another social class, this would have been the reality. Graham makes the point clearly without labouring it.

When The Children who Lived in a Barn was published in 1938 childhood for most children was short. For many children it was about to get an awful lot shorter. When it was re-published in 1955, children across Europe had found themselves more alone than the Dunnets, and with enemies far crueller than an interfering District Visitor.

quotes … do share your favourites

‘The children were accustomed to helping and swept, dusted, washed up, prepared vegetables, and so on quite peaceably – and the occupation steadied them. Only Sue felt all the time that it was funny not to have mother there to direct affairs and to take the responsibility for everything off her shoulders.’

‘The family’s rapid pack-up and removal to the barn took the ladies by surprise, though the rest of the village knew about it the same night. But Mrs Legge and her friends had not been idle. They had spent a good deal of time discussing the whole difficult situation and felt that the family ought to be thoroughly grateful.’

‘”You’re quite a little mother, aren’t you?” said Mrs Durden and did not see Sue wince.’

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

The Home-Maker by Dorothy Canfield Fisher (Persephone Book No 7)

A London Child of the 1870s by Molly Hughes (Persephone Book No 61)

The Young Pretenders by Edith Henrietta Fowler (Persephone Book No 73)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

I can only begin to imagine how completely I would have escaped into this book as a child, and though my original copy is lost I remember the cover very clearly indeed and I probably wanted my mum to cook something in a hay box, just to see, in fact I have an urge to stick a rabbit casserole in one right now and see if it works.

It occurred to me that, with its original 1938 publication, I could easily be reading a book written as the portents of war loomed overhead and here was a fine example of resilience in adversity and children taking responsibility for their own welfare that may well be needed in the months and years to come. dovegreyreader

Could any kids today survive in similar circumstances? Could kids in the 1930s or the 1950s really have coped this well? These are the questions you’ll be asking yourself if you read this book. And presumably it was somebody asking something along these lines that made me want to read it in the first place. And I’m glad I did. harrietdevine

Graham provides great insight into family dynamics, the importance of self-sufficiency, and finding strength in adversity, while also giving us plenty to think about with regard to welfare and human kindness. goodreads