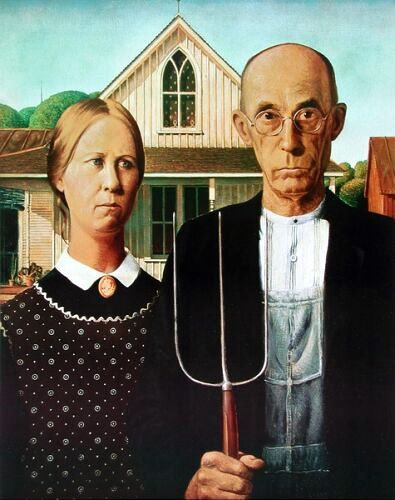

In the early 1980s I saw a short film set in the American Midwest at about the turn of the century. Two women, with their husbands, the sheriff and the county attorney, go to an isolated farmhouse, where a man lies dead. His wife has been arrested for his murder: he died, Minnie says, ‘of a rope round his neck’ – what a haunting line. The men look for hard evidence of guilt, and find none, but there are clues in the bleak, cold kitchen which the women find and keep to themselves. They understand what the men are incapable of understanding. Minnie has been pushed beyond her limits in a lonely and abusive marriage, but their lives, too, have been hard, in a world in which male authority may not be questioned, and where emotion must be held in check.

I did not recall the name of the film, and at the time took no notice of the author of the original on which it was based, but the image of the grim, colourless farmhouse has stayed with me and this is the picture that I had in mind when I first read Brook Evans. Not until I opened Elaine Showalter’s excellent book on American women writers, A Jury of her Peers (2009) did I make the connection: the film which had left such an impression was Trifles and the screenplay was based on Susan Glaspell’s first play, written in 1916 for the Provincetown Players, a theatre group set up by Susan Glaspell and her husband, ‘Jig’ Cook. ‘Grey calico she wore, moving from room to room in that gaunt, lonely house’ is how Brook remembers her mother long after her death. That gaunt, lonely house is not so very different from Minnie’s house in Trifles.

Twelve years separate Trifles from Brook Evans, and when she wrote Brook Evans in 1928, Glaspell had been away from Iowa fifteen years, living in Provincetown, New York, and Greece, before returning to Cape Cod in 1924, following the death of her first husband. The homesteads she paints have lost none of their vividness, and none of their power to nurture and to destroy. These houses are more than mere buildings, of wood, or stone, or bricks. They are symbols of the constraints and the consolations of family life. A house is where a man exercises his authority, as a father and as a husband, and works to keep food in the mouths of his family; and where a woman puts up cherries for the winter, and launders, and tries to keep the peace, but, ultimately, submits.

Two houses lie at the heart of the novel. The atmosphere and the power of both are wonderfully described, the almost cloying cosiness of the Kellogg house in the opening pages giving way to the cheerless isolation of the Evans homestead. There are messages in the shape of houses: Naomi Kellogg, the oldest daughter, finds her own to be welcoming because it has a porch, whereas the grander house of their neighbour, the disapproving Mrs Copeland, widowed mother of her lover, Joe, has a “stoop”. But it is no coincidence that her bedroom is in the ‘ell’, in the extension, slightly apart, like Naomi, attached but not integral. From there she can escape unnoticed to meet Joe, and hear the flowing brook which speaks to her of freedom, a life beyond, and love, not everyday homely love but passionate, romantic love, a permanent escape. A cruel accident prevents this.

Passion so nearly prevails, but the forces of respectability require that she marry the unattractive Caleb Evans, with his ‘thin, uncertainly moving shoulders, and his high-pitched voice, who ‘made her think of someone in a silly play, pretending to be alive’.

Naomi is expecting Joe’s child (I was shocked to realise, on second reading, that making love to Naomi, Joe was excited by the thought of Caleb’s having proposed to her and being refused). The Kellogg house is not big enough to contain her shame. Caleb takes her to a new and harsher house, deep in the mountains of Colorado. The old home where ‘the wooden seats of chairs were rounded, stair rails were smooth, table legs battered’ had closed its door against her, and she would never turn Caleb’s house into a home. For want of company the golden oak furniture in the parlour would keep its sheen. Only for her daughter, the eponymous Brook Evans, would she make a room pretty. And for Brook, she has Caleb build an ell. Her daughter’s room is to be just like hers, and must offer the same possibility of escape. The young Brook is less driven than her mother by a need for personal fulfilment, but whether she wants it or not she must live out Naomi’s lost dreams.

Books 2 and 3 are the very core of the novel, and brilliant. The narrative thread weaves backwards and forwards, sometimes within one paragraph. I found myself rushing to turn the pages to find out not what happened next, but what happened before. How had we got here? The characters prove to be far more complex than at first appears. Good Naomi is less likeable than she seemed at first, Caleb more to be pitied. The descriptions of their miserable attempts at sex, hardly love-making, are graphic for the time and almost touching. Caleb seems more awkward than cruel. It is a loveless marriage, but a warm companionship develops for a while after the birth of Brook. ‘They laughed together the first time Brook threw the bottle she had emptied ….. soon it was the baby gave them something of a life together. Worries when Brook was not well, thankfulness as an ailment passed, this at times could bring the feel of home into their house.’ The loss of a second child is shocking, but the grief is shared and Naomi gives herself wholly to helping her stricken husband through a paralyzing mourning.

Caleb loved his son, but he also loves Brook, who is not his daughter, and she loves him, when she thinks he is her father, and loves him more when she knows he is not. Naomi had not expected this, ‘there had been one thing for which she had lived. She would one day tell Brook that she was the child, not of a loveless marriage, but of a love nothing had been able to stay. She would give Brook to love, and that would be giving Joe his child’.

But Brook hadn’t wanted to hear. She is embarrassed, as any daughter would be, She is embarrassed, as any daughter would be, ‘almost as if Mother had taken off too many of her clothes.’ Naomi cherishes her daughter, saving little treats for her, even stealing money from Caleb to give her the clothes she wants, but much of it is a sort of grooming: she is making Brook ready for love, for the great passion. But Brook is not only her daughter and Joe’s daughter, she is also the grand-daughter of the cold straight-backed Mrs Copeland, who ‘could hold herself like that because she had always held away from people’. She is sorry for her mother, ‘it was too bad she had had to work so hard and had been so much by herself’, but finds it hard to hug her. ‘Brook was polite, kind to her mother – a Christian sort of kindness, Naomi thought bitterly.’ The relationship is awkward, and perfectly caught in Glaspell’s dialogue, countless little scenes which catch to perfection the rhythms of their speech, and the things unsaid, and could go straight from the page to the stage.

Brook’s escape, when it happens, is not the one Naomi planned, and set up for her. The dream which Naomi had carried with her for nineteen years, stunting her own emotional growth and distorting her daughter’s, is not be realised. Not yet, and not in her lifetime.

The novel could almost end there. But Brook must discover the powers of love. And, belatedly, she does, but she discovers that following her heart requires that the needs of her family be overlooked. Her father will die without seeing her. Her young son must travel alone to the old Kellogg home, no longer isolated – the town has crept up on it – and lacking most of its early charm, ‘improved’ by the addition of a concrete wing, and a garage obscuring the view from the ell, where Naomi Kellogg had her bedroom as a girl and where her widower husband is spending his dying days.

Will she be happy with the mad mathematician, Erik Helge? Brook is in love and so is Erik, but there is a premonitory flash of disappointment when she goes to meet him and finds that he is not watching out for her, as she would have been for him, but absorbed in his work: ‘It would often be like this. ‘It would often be like this. She would not have it otherwise; she loved him for this, she told herself, as across the street she halted, watching him’. Erik holds out the romantic promise of walking barefoot in China. He is a ‘violent, electric person’, exciting and passionate but is he kind?

“As before they stood still listening to the trees; though it was not as if they paused “ listening, but as if halted – stilled – for some old message, some meaning.”

I felt inclined to warn her against him, to suggest that the kindly Colonel, friend of her late husband, would be a wiser choice. Susan Glaspell, the romantic, wants it to succeed. Her husband, Jig Cook had died in 1924, and when she wrote Brook Evans she was living with a much younger lover, the writer, Norman Matson. But somewhere in the background I could hear the voice of reason. In Suppressed Desires: A Freudian Comedy, a play written with Jig Cook, the following exchange takes place: “What am to do with my suppressed desire?” Mabel asks, and Stephen answers, “Mabel, just keep right on suppressing it!”. The play was written in 1915, the year in which Fidelity was published. What is one to make of it?

quotes … do share your favourites

‘Nineteen years had not smoothed or scuffed the golden oak into a home. Ashes had not been spilled from pipes, nor were there the only half rubbed out rings of glasses too cold or cups too hot. Quite different was her own home, the low house under the great trees. The wooden seats of chairs were rounded, stair rails were smooth, table legs battered, and old stains but half worn away, were sometimes beautiful when the light moved over them.’

‘Heartbreak, yes. “I broke her heart†Brook said, sitting very still before her desk, facing it as she had never faced it, wanting now to know, not so much either to vindicate or to blame herself, as somehow, though too late, to clear a place between her and her mother, wanting understanding to be there, if only for its own sake, and so at last, asking, searching.’

‘What would happen if every one were to give up what there was between what they were supposed to know and think, and what they really did know and think? It was from that place, perhaps, came the “Intimations” – from that place we reached each other, without ever letting on.

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Fidelity by Susan Glaspell (Persephone Book No 4)

They Were Sisters by Dorothy Whipple (Persephone Book No 56)

Hetty Dorval by Ethel Wilson (Persephone Book No 58)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

‘It’s powerful and emotional and desperately, desperately sad, especially towards the end, when Brook is filled with regret towards the way she treated her now dead mother. It is similar to Fidelity in that it shows Glaspell’s obvious belief that love was the ultimate prize in life and that nothing should stand in its way; a life without love, once love is known, is a life of bitterness and yearning for a happiness that will never come again; a life without love, when love has never been known, is always going to be a life of unfulfilment and an unknowing emptiness.’ booksnob

Fidelity by Susand Glaspell, written in 1915, and also Brook Evans, impossible to choose one over the other, as Glaspell is so shockingly ahead of her time. mrsminiver’sdaughter