Talking with friends last week about significant books in our lives, we all agreed that Ballet Shoes had to be on the list. Three orphan foundlings delivered by a mysterious and absent elderly professor, to be cared for by a large, practical, warm-hearted nanny, a good plain cook, two maids, and a sensible and resourceful guardian, in a house firmly sited in London’s Cromwell Road, and serendipitously filled with lodgers who in a variety of ways, magically smooth the children’s paths in life. There is never any suggestion that a lack of parents might be a drawback. Quite the reverse. Parents have needs, and lives of their own. In the world of Ballet Shoes, and this is what made it such a wonderful read, over and over again, children come first, always.

The opening pages of Saplings seem momentarily to be taking us into that world, a world of shrimping nets and spades and sun and no lessons, with a sensible, but indulgent governess and a warm, bulging nanny to bring milk and buns to the beach in her bulging bag. Mum’s camp stool is waiting for her on the sand, and Dad has joined the holidaying family. Big sister, Laurel, turns cartwheels of joy, while brother, Tony, inwardly exclaims, ‘Whoopee! What a day it was going to be’, and adored, beautiful and gifted, but difficult, Kim rates the day as ‘scrumptious’. Whatever the language might suggest, we have not strayed into the land of Ballet Shoes.

There are clouds on the horizon. It is the troubled youngest, Tuesday, who has been the first of the children to sense the adults’ fears, ‘because she was only four, and people underrated her intelligence and spoke in front of her’. In a man to man chat on the beach Alex Wiltshire confides in Tony that he will shortly be returning to London on war work, stressing that he should say nothing of this in his mother’s hearing. A ten-year old boy can be entrusted with information that cannot be shared with his mother. There is a war starting and the Wiltshire family is not as solidly functional as the opening page suggested. The coming years will test it beyond its limits.

Alex Wiltshire is without doubt the model Dad, solid as a rock, devoted to his children, but not afraid to show a bit of toughness when called for, straight-speaking and, apparently, fearless. Most unusually for the period, for any period, he has, discreetly and without show, taken charge of the children, clearly recognising from the start that his beautiful wife was not of the stuff mothers are made of. Or perhaps he didn’t give her a chance, assuming control of the nursery before she could take her first faltering steps as a mother.

By the time we meet Lena, she is the thirty-three year old mother of four, but is quite clear about her role, ‘The children were darlings, but she was not a family woman’, ‘she never even pretended the children came first’. What she wants is to be a wife. Streatfeild does not underplay the importance of sex for Lena; later she will even find air-raids arousing, to the point that Alex worries about his own ability to ‘keep up the pace’ if the nightly bombing continues. She uses all her whiles to keep him up to the mark, knowing that ‘if he was once permitted not to answer smile for smile, and covert look for covert look, he would be one shade nearer that dreary he wanted to be, the perfect father, the family man.’ She wants him to be her lover, and as the saying goes, the children of lovers are orphans.

Her own parenting had not given her much of a grounding, ‘Her mother had always been her ideal of all that was feminine and delicious. It had not hurt her as a child to be petted and exhibited one moment and to be shut away in her school room or nursery the next …’. Mum’s-mum, tellingly not Gran as ‘good’ granny Wiltshire is known, had taught Lena, her only child, that what mattered most in life was to look nice, to have fun, and to be ‘happy’. The ‘drearies’ of child rearing are not for her: but she works hard at their appearance – well dressed children make good accessories for the chic mother; and she is good at orchestrating ‘fun’. ‘Lena’s policy with her children had always been that they should be charmed by her. She would be a mother to admire, who was a little apart from the humdrum side of life’.

But even her mother in law concedes that ‘up to a point she’s a good mother’. Her interest in her children is intermittent, and self-centred; in many ways she is still a child herself, but she has a gift for home-making, which Alex appreciates, and the children, rightly, take for granted. With a steady father and the haven of a more than comfortable London house, Laurel and Tony, and Kim and Tuesday could have weathered the storms of growing up. But war, as Lena rightly perceives has ‘no use for delicate adjustments’. The carefully constructed continuity of their lives is first cracked and then broken into pieces. Home would be the first casualty of the war.

Bit by bit the family unit is reduced. Children, as Nannie later reflects, ‘are best where they belong. They miss having their rightful things.’ Sent away from London and the danger of bombs, as the war grinds on they find that they belong nowhere, and that few things are rightfully theirs. For Laurel and Tony things and space become all important. Laurel’s fragile equanimity is shattered when she finds herself moved out of ‘her’ room into her grandfather’s dressing room,to make room for evacuees, while her brother’s is challenged when he is forced, unfairly he considers, by the influx of boys and the call-up of young masters, to share a desk at school. Neither of the older children is helped by their father’s well intentioned lessons in keeping a stiff upper lip in the face of adversity. They cannot handle their anxieties, but nor can they share them.

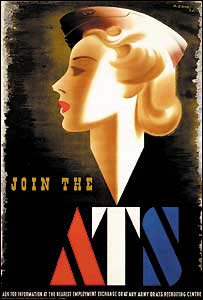

The war has not finished with them. In one dreadful blow, temporary evacuation from their home, and temporary separation from their father are made permanent, when a bomb destroys their house and, crushed in the debris, Alex is killed. Lena alone cannot hold the family together. Ruth Glover, the children’s governess, and the voice of reason (who would later have a ‘good war’ in the ATS), assesses the situation, with anxious clarity: ‘Take away Alex and had she anything to fall back on? Her life had been built like a game of spillikins with Alex as the bottom spillikin on which the whole structure stood. It was impossible that the structure would not collapse when you tore out the bottom spillikin.’

Countless other women were and would be in the same situation. War was making absentee fathers the norm. Laurel’s headmistress reflects coolly, ‘It’s been my experience that if the mother makes a decent home not much harm’s done’. Lena does her best to rebuild a home for the children, and comes close to succeeding, but missing the support and sex that she had from Alex, she falls easily into the arms of a visiting American serviceman. The children might have adapted to that. Walter is a good man; the children like him (always the acid test) and, in his way, he cares for them, but he too is called away.

One blogger describes Lena as promiscuous, which strikes me as unfair. Had there been no war, Lena might have remained a more than devoted wife to Alex and an adequate mother to her children. She is quite undone by the war. Her limited reserves of strength are quickly depleted, but she must keep up a good show. What could be easier, or more destructive, than to turn to the bottle? (The graphic description of her slow, ugly and humiliating decline suggests that Streatfeild had observed the alcoholic at first hand.) The fragile family unit, just managing to survive the ravages of war, is finally broken by alcohol.

The children are to be divided up between the aunts. Three of them with husbands in the services are coping alone for the duration, and Sylvia, the youngest and closest to her brother, might as well be alone for all the help she gets with her five children from her unworldly vicar husband. They are four very different women, in their thirties and forties, none having much time for Lena – self-indulgent, flighty and over-dressed – and still settling childhood scores between themselves. Lena may have proved herself worse than most, but no mother is perfect and each of the Wiltshire women represents a different kind of imperfection. Dot works too hard outside the home, Sylvia has more children than she can manage, Selina is overambitious and Lindsey, writer and self-styled child psychologist, for all her professional pretentions knows nothing of the practicalities of parenting, what Dot refers to as ‘the nappies, school bills, sick in the train knowledge’. Nevertheless, it is part of Dot’s scheme to ensure that she does her share. And so Laurel finds herself, in a cruel billeting arrangement, with the aunt least able to care for her.

There is a fourth family, the Parkers. Albert and Ernie, evacuated, at the insistence of their father, are billeted on the Wiltshire grandparents. For all their rough edges the evacuees have learnt something that Lena’s children have missed: ‘the whole of their upbringing had taught them to put the welfare and happiness of small children before everything’. Cruelly it is their mother’s love that kills them – missing her sons so much she insists that they return to London. A bomb leaves Mr Parker a childless widower. Too much love, of the wrong sort, can kill. Not enough can leave a child weakened for life.

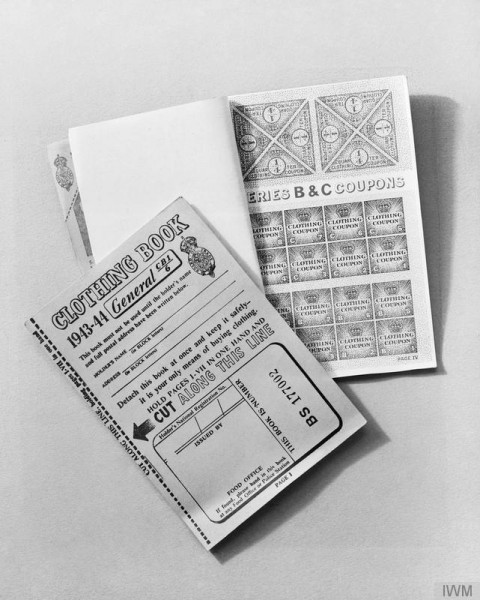

The Wiltshire children are very different in appearance and character, a diversity contrived to demonstrate the underlying strengths and vulnerabilities that will determine the outcome for each of them. Laura, plain, anxious, at first eager to shine, and, failing that, to merge into the crowd, is mortified when wartime rationing keeps her in a green school uniform, when all the other girls are in brown. Without the war, or rationing, or the loss of her father’s gentle encouragement, she might, as he hoped, have dare to blossom. But a combination of history, bad luck and an increasingly desperate need for more TLC than was available for any child in such troubled times finally brings her down.

© IWM (D 14000)

Tony’s fierce sense of right and wrong, gently guided by his father, might have been an asset; without that guidance, it sets him against the world, and the brave little boy becomes a sullen, friendless teenager. Little Tuesday, dosed with powders when we first meet her, is still sleep walking four years later, but no-one has time to worry about her. Only Kim, who was always considered the problem child, and who, ironically is the most like his mother, ‘able to play himself like a Wurlitzer organ’, is by the end, in Ruth’s words, ‘doing nicely’. Is Kim naturally more resilient? Does his strength come from having received the lion’s share of his mother’s love? Are some children, like Ruth herself, born survivors?

Kim speaks for all children, when he explodes: ‘But we’re children. It’s us that people have to bother about. Children don’t have to bother about grown-up people’. The tragedy of Saplings is that, because of the war, not enough of the grown-up people had enough strength or enough time to bother about the children

Quotes ….. do share your favourites

‘What a picture they must look, and the thought amused rather than pleased her. There was nothing she liked better than to be envied and admired, but this was not the picture she wanted exhibited. That picture was of her and Alex. Of course the children must be there too, but as charming decorations, not interfering with the original portrait of two people.’

‘This passion for being the centre of the picture was dangerous. What on earth would he [Kim] grow up like? It seemed unnatural that before he was eleven he should have found a way to adapt his failings to feed his egoism. If all went well Kim might do anything, but what if things did not go well? He could never be poor. He would always have to throw his weight about, be surrounded with friends, even if he had to rob a bank or forge cheques to do it.’

‘Heaps of  children grew up without much attention and turned out alright in the end … Heaps did, but were they the Laurels, Tonys and Tuesdays? She [Ruth] herself had grown up all right with very little attention, and little of it wise.All right but bruised. The Wiltshires were having a harder upbringing than she had. If only bruising was all they got out of it. What if they grew mis-shapen?’

and questions

Is it possible to speculate about would have happened to the children if there had been no war? If Alex had not been killed? If Elsa had not put Laurel in the Colonel’s dressing room? If Laurel had not moved schools? If she had had the right uniform? Is it big events that alter things? Or does fate turn on smaller points?

Is Lena promiscuous, as one blogger calls her? Sex-obsessed, as Jeremy Holmes writes?

Which of all the mothers that Streatfeild presents to us in Saplings can be termed ‘good enough’?

If you have enjoyed this book, you might also enjoy:

Hostages to Fortune by Elizabeth Cambridge (Persephone Book No 41)

The Children who lived in a Barn by Eleanor Graham (Persephone Book No 27)

Doreen by Barbara Noble (Persephone Book No 60)

The Young Pretenders by Edith Henrietta Fowler (Persephone Book No 73)

Princes in the Land by Joanna Cannan (Persephone Book No 63)

What other bloggers have said about this book:

This heart-wrenching and painful book really packed an emotional wallop for me. It is not what I would characterize as one of those “charming” books I love to read. In fact, at times it was downright difficult to read, but I still really came away loving this book. Sounding a bit contradictory arn’t I? I just found this book to be a powerful and moving story about the sad destruction of a family. jeannetesbooks

What a brilliant book Saplingsis. I had never read Noel Streatfeild before (no, not even Ballet Shoes), so I had no idea what to expect. Well, it turns out that she is an excellent writer: subtle, perceptive, sensitive, occasionally ironic, everything that I love. Saplings reminded me a little of A.S. Byatt and (don’t laugh!) of D.H. Lawrence. It was something about the way she uses multiple points of view, jumping from one perspective to another quite frequently, and yet still managing to make it work. I always admire writers who can pull that off, as I imagine that it takes a lot of skill. But most of all, it was the way she wrote about her characters with such tenderness, such care. I loved them; I felt for each and every one of them, no matter how flawed they were. thingsmeanalot

Saplings is beautifully written. Streatfeild’s descriptions are wonderful: in the first few scenes at the beach, I felt that I could hear the sea, really see the children and the hazy glow, almost as if in my own memory. She paints such clear characters, that a few days after finishing the book they are all still vivid in my mind. Although the book has a central story, I did feel that it was more of a sketch and I do think you need to sort of settle into it rather than being in a rush. I will admit that at first didn’t find myself wanting to pick it up all the time but when I was reading it I became absorbed. I did feel that there were some slightly contrived parts in the novel but similarly I think that this reflects that the book was written for a purpose and to make the reader think novelinsights

5 replies on “Persephone Book No 16 Saplings by Noel Streatfeild”

This one is major!

Having grown up on Noel Streatfeild’s better-known books, it was quite a surprise to find her writing about subjects like bed-wetting and adultery. But her voice is recognisably the same and, as always, she is concerned with the moral life of children.

The Wiltshires are an affluent family. They can afford a house in town and another in the country, boarding schools and domestic help. But although this author is well aware of poorer families, like the two little evacuees from London, she chose to make this family well-off so she could concentrate on the problem of emotional starvation.

I’ve seen children cope remarkably well after a parent dies – but only if the other parent is completely reliable and devoted. Lena isn’t, because she is what our ancestry used to call ‘man-mad’, and although some teachers and carers do what they can it is never quite enough. The scenes near the end where the various aunts discuss who shall take which child for the school holidays are painful to read. (It can be confusing, all those aunts and cousins, take a little time to sort them out!) And the behaviour of Laurel’s teachers at her second school is brutal; thankfully, I believe, teachers aren’t allowed to abuse children any more. The book was published at the very end of the war, and all the children have survived, but three of the four are likely to be damaged for life. The exception is Kim, who is a common type in Noel’s work, like Maurice in ‘The Painted Garden’. I can see him becoming a popular radio host or television personality when he grows up, but the others? Will they pass on the damage to their own children, deepening like a tidal shelf? She doesn’t say.

It’s extraordinary that this wonderful book was allowed to go out of print. Presumably, people couldn’t think of Noel as anything but a sunny-natured children’s author.

Another wonderful book is ‘Doreen’, which I thought when I first read it was better than ‘Saplings’, because it concentrates on just one child evacuee. But then having re-read ‘Saplings’, which works so well as a family history, I think they are both indispensable;!

I like the way Streatfield’s writing about children connects effortlessly with her writing about adults – the same sharp observation not unmixed with sympathy works for both.

Again, thank you Persephone for continuing to publish a collection of otherwise-neglected works. I thoroughly enjoyed “Saplings.”

Streatfield’s novel captures an era only dimly known to me, a time when my own mother was a young woman making her way in New York. For me, two scenes reminded me how this wartime era straddled so many decades:

Bathing Machines! On the very first page, Streatfield mentions the bathing machines at the beach. I puzzled over the machines until I looked them up on Wikipedia. Victorian England yes, but it’s hard to believe these contraptions were still used in the 1930’s and 40’s.

The other extreme appears on Chapter XLVI (page 319 of my edition). Aunt Lindsey, the most independent and self-absorbed of the siblings, and Laurel are saying goodbye. And what could be more 21st century than the perfunctory “Have nice day”?

She [Laurel] blurted, ‘Good-bye, Aunt Lindsey. I hope you make no end of a good speech.’

Lindsey smiled.

‘Thank you.’ She gave Laurel and brisk, meaningless kiss. ‘Have a nice day.’

No sooner had I finished this (this morning) than I dug out the tapes I made of the Radio4 readings done in 2004 (I think). Mistake! Though I know books and broadcasts are different things, and I enjoyed the readings the first time around – before I had read the book – I thought she had shifted the dynamic of the story quite a bit by leaving out Tuesday and Uncle Walter, and why make silly little alterations like changing the colour of Laurel’s missing new school uniform from brown to red and blue?

I thought the relationships between father and children not unlike those in Dorothy Canfield Fisher’s ‘The Homemaker’, though the mothers are not the same at all. In fact, on thinking back, the children also make me think of Daphne du Maurier’s ‘The Parasites’, published 5 years after. Those lost Delaneys could be the Wiltshire in later life.

The one sentence which will live long after the whole book has faded is the one describing Laurel’s body, which ‘housed a creature floundering in the mud and flowers of adolescence.’ Isn’t that just perfect? Just what the horrible uncertainties of growing up are like.

Now, the story I’d really like to read is the tale of Uncle John and The Foxglove. That was so sympathetically done in the book, yet made entirely lascivious on the radio because Aunt Lindsey was given the speech with Laurel which was only referred to by Streatfeild herself.

As a child I read ‘The Years of Grace’ edited by Noel Streatfield. Published in 1950, the book was prefaced with a portrait of the editor, whose distinguished appearance suggested a thoughtful and kindly person. The book contained well-meaning guidance for children in their early teens and I particularly remember the section on clothes which advised me to get a grey flannel suit and a net party dress, as being most suitable for my age.

Noel Streatfield’s sympathetic interest in children and their development is evident throughout ‘Saplings’, a story which took me straight back to that late 40s/early 50s period. Reading it sixty years after its first publication it is surprising to find that so many household staff were still in evidence after the war but less astonishing to find that boarding schools were there to be endured if not enjoyed. School fees seem to have presented no problem. Noel Streatfield’s theme in ‘Saplings’ is that deprivation is not necessarily material, and her aim is to show how much children can suffer from a death in the family and the break-up of a family home. I found her treatment of the children’s trials very sympathetic, feeling particular compassion for Laurel who seemed to have an unnecessarily hard time.

Noel Streatfield is also concerned here with adult motivation, which leads to a mild sense of exasperation at how badly everyone misunderstands each other. Couldn’t someone have prevented the children from being split up in the holidays? Couldn’t Grandfather have come to the rescue at an earlier stage? The author conveys a good understanding of her characters’ problems and afflictions but her writing sometimes seems constricted by contemporary attitudes to human frailties. Lena’s need for alcohol and sex always seems to be mentioned in hushed tones, whereas poor Tuesday is left to cope with her enuresis alone as no one seems capable of mentioning the words bed wetting. The reference to ‘the physicals’ sounds very alarming and is passed over with a quick shudder.

Noel Streatfield has an easy narrative style and I enjoyed the main story, but was left with a slight sense of dissatisfaction at the end. The numerous subsidiary characters seem to be rather one-dimensional stereotypes. The Colonel is dignified and perceptive and always carries a copy of the Times; Nannie is comfortably shaped and has conservative opinions; Mustard (a great name for a gardener) is dependable and loyal; Uncle Walter is the generous war-time American serviceman; Uncle Charles puts in a brief appearance as the nouveau riche businessman. The evacuees are a colourful but not entirely convincing addition to the cast. The structure seems to weaken in the last part of the book, which comes to rather an abrupt conclusion, but perhaps it is to the author’s credit when the reader is left wanting to know what happened to the main characters in later life. I think the poignancy of the Wiltshire children’s story makes ‘Saplings’ a worthwhile read for adults but occasionally the plot does seem rather forced. I much preferred the magic of “Ballet Shoes”.